Zack Snyder’s Sucker Punch currently has a rating of 2.2 stars out of 5 on the movie logging app, Letterboxd. The film came out in 2011 and the site was popularised in 2020, so in just under two years, about 100,000 people took the time to log the movie on their profile and give it either a uniformly mediocre rating or – more likely from a cursory look at the individual reviews – widely disparate ratings pulled towards a meaningless average. More than ten years after it first came out, the movie is still as controversial as its director Zack Snyder.

But is Sucker Punch actually a bad movie? Were the critics, accusing him of blatant, if not lazy, accidental misogyny, right? Could Zack Snyder’s film now be considered a groundbreaking feminist piece of work? Could the lack of subtlety be where the nuance resides? Zack Snyder is one of the most prominent figures in pop culture, the sort of bombastic blockbuster powerhouse that the critics love to, well, criticize. Did Sucker Punch suffer from its director’s reputation, or did it help to burnish that reputation?

The short answer to all those questions is that Sucker Punch is neither a feminist movie (what is a feminist movie anyway?) nor did it receive the consideration it actually deserves. The film actually merits much more credit than it was given by dismissive movie critics. Limiting it to an action movie about ‘hot girls in short skirts’ was not only over-simplistic but also completely erased any kind of nuance that the director attempted to create.

Sweet Dreams Don’t Last in Sucker Punch

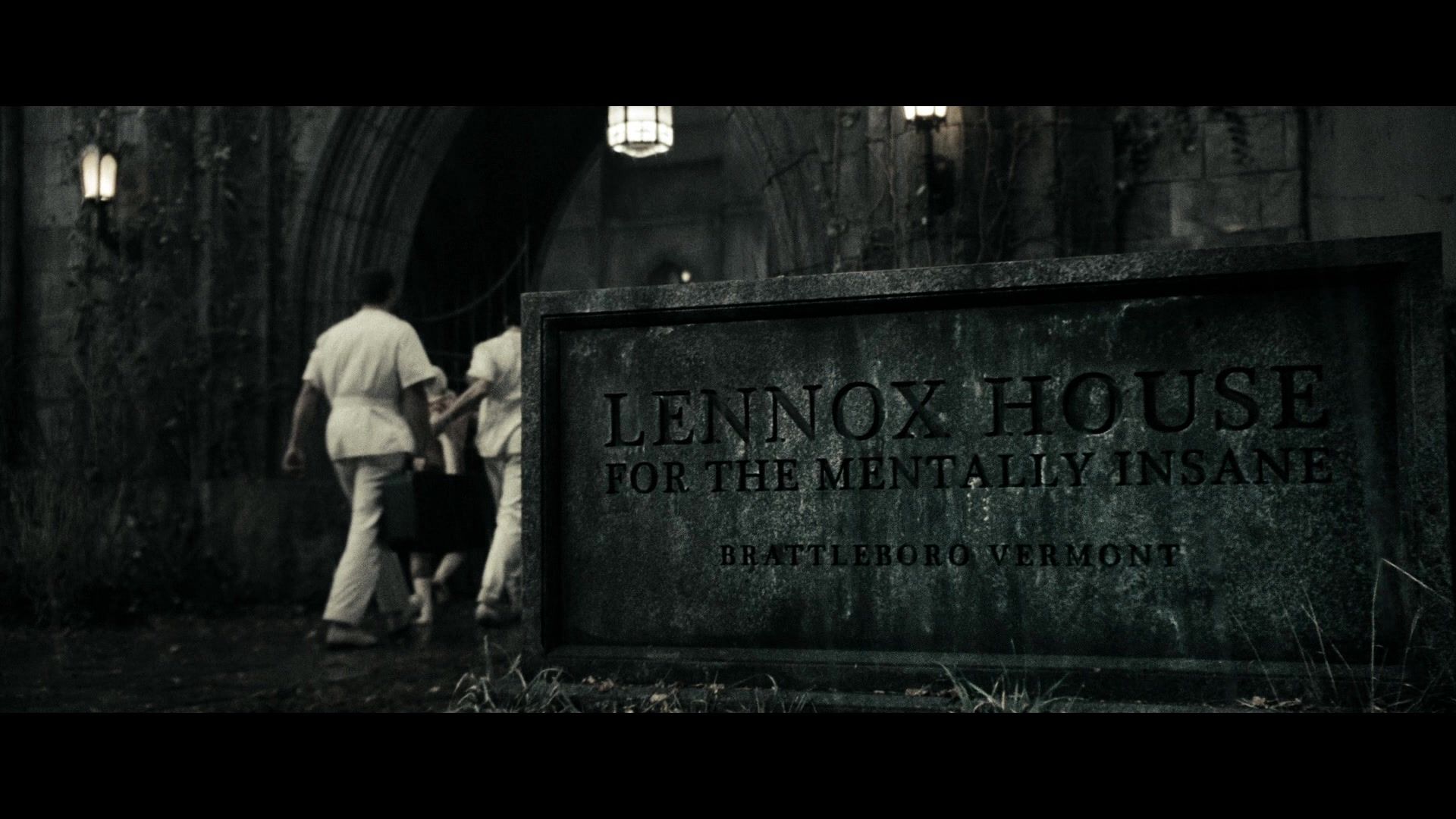

Ten years later, while many have forgotten, consciously or not, this movie, some of us remain, tirelessly defending it to whoever gives us the time to hear our tirade. The first six minutes – effectively the opening scene – are enough to set the mood for the entire movie. With its greyish, greenish filter, its melancholy cover of ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)’, everything is set: we will be following the disastrous destiny of a young woman, Babydoll, played by Emily Browning, framed by her abusive step-father (Gerard Plunkett) for the death of her sister so that he could access the inheritance left by their recently deceased mother.

One thing leads to another, she is committed to a mental hospital and is set to receive a lobotomy so that she can never get in the way of the inheritance. Although the abyssal structure of the movie gives a sense of hope for the young protagonist’s future – (spoiler alert) – there is no happy ending. Sucker Punch is not a happy tale, it is a story of power struggle, male domination, and enslavement.

As said earlier, this fantasy movie cannot be considered a feminist piece of art as it doesn’t openly serve a political agenda, however, it is interesting to use feminist frameworks to analyze the way the women protagonists are filmed and portrayed. Because despite what the critics led the public to believe, Sucker Punch is actually much more than another hyper-sexualized action movie.

In her 2020 essay, The Female Gaze: A Screen Revolution, French journalist, and essayist Iris Brey draws a framework similar to the Bechdel Test, to help people analyze more easily whether the technique of the female gaze has been used in a movie or not. While this technique is not necessarily entirely relevant in the case of Sucker Punch, it remains extremely interesting to establish a first-hand analysis of the way women are portrayed in the film. Both the male gaze and the female gaze (the former being the foundation of the latter, which was theorized in the ’80s by movie critic Laura Mulvey) don’t denote the gender of the filmmaker but serve as a conscious aesthetic stance that moves the woman protagonist from the object of desire to the film’s subject on their own terms.

Narratively speaking, Sucker Punch easily passes the test: the main character, Babydoll, identifies as a woman, the story is told from her point of view, and the story questions the patriarchal power dynamic. Very quickly, within the very first two minutes, we understand the story is framed by her (unreliable) perceptions. The opening scene propels us into what seems to be a theater, with a whole bedroom set on the stage. Babydoll is sitting on her bed with her back to us. As the camera slowly moves towards us, the theatre seems to be transitioning into her real house. We can feel her fear, her pain, and her sadness.

The close-up of her hand tightly holding the sheet covering her deceased mother is a vehicle for pain. Her eye watching through the peephole in the door while her stepfather is trying to capture her sister is the means by which Babydoll is positioned as central – this is her story, and she is sharing it with us. Later on, when she is admitted to the mental hospital, and listening to her step-father and hospital orderly Blue Jones (Oscar Isaac) negotiating her monetary worth, her face is divided in two, while still facing us. When her step-father, situated behind her on her left, talks, only the left part of her face appears, and vice versa when Blue Jones talks. This is a way to give her back her humanity, to make her subject and not only the object of discussion. With this technique, Zack Snyder allows us to listen to the discussion from her perspective rather than simply watching the two men talking about her, without her.

Don’t Call Me Baby (Doll)

Not only is Babydoll the main character, but she is also sharing her testimony, her emotions, and her feelings throughout an extremely objectifying experience. The irony of this movie is that, while it easily passes the first part of Iris Brey’s test, it barely passes the Bechdel Test, another tool to measure the representation of women in fiction. Yes, there are more than two women in the movie. Yes, they talk to each other, and about something other than about a man. But are they actually being named? Are the infantilizing nicknames – Babydoll, Sweet Pea, Blondie, Rocket, and Amber… all made to be slurred through acrid cigarette breath with an unwelcome hand on the thigh – enough to qualify them as named?

This is where Sucker Punch‘s greatest strength resides – but, also where the critics were at their harshest. Nick Schager wrote in Slant Magazine:

“Yet Snyder’s conception of his heroines—who are asked to do little more than pout, strut, glare, and look fierce—is pure nonsense, since, like the story’s villains, his film reduces them to mere objects of carnal desire, and ones whose physical prowess and take-no-shit attitudes is less a face-slapping rejoinder to sexism than a manifestation of amalgamated male desires.”

This is the easy way out. At first glance, the movie, is, indeed, everything described above, and seeing anything else required more work than many viewers were prepared to invest. Sucker Punch is a deconstruction of pop culture’s hyper-sexualization, and its pornographic and patriarchal beauty codes, overly prominent in everything that we watch and consume today.

When Babydoll is asked to dance for the first time, as she will, later on, have to perform on stage in front of a crowd of disgustingly powerful men, Björk’s ‘Army of Me’ starts, and the set suddenly changes from a dance hall to the court of a Japanese temple. The first fight scene remains, not only the most powerful one, as it is our first journey into Babydoll’s mind (“Stand up/You’ve got to manage/I won’t sympathize/Anymore,” Björk howls), but also the most significant one.

As the decor has transitioned, so have the main protagonist’s clothes. When she was previously wearing a greyish, slightly torn, sailor-type dress, she now appears in much shorter, much cleaner outfits. A two pieces ensemble of what was the sailor dress. The high, black stockings that stop mid-thigh and her black high heels, although remain as previously. While her daily outfit is nothing of the realm of the casual and comfortable, mostly when it comes to executing chores, this second outfit is an open reference to the world of hyper-fetishization.

She will then proceed to combat three giant Samurai – feeding her a glimpse of an escape plan. Once she has stopped the Samurai, she transitions back to reality, in a room hypnotized by her dance, as much as we were with the combat scene. There are no obvious reasons for such a costume choice. Furthermore, while Babydoll has the privilege of an entire dress, most of her companions, played by Vanessa Hudgens, Abbie Cornish, Jena Malone, and Jamie Chung, are simply dressed in a bodysuit, corset, and clear black stockings.

Not only was this choice conscious – as Zack Snyder explained during an interview for Vanity Fair: “I was asked at the time: ‘Why did you dress the girls like that?’ And I always go ‘I didn’t dress them like that, you did” – but it was a way to reuse the codes of sexual exploitation in a story of sex trafficking that, by the way, featured no actual sex scenes.

Voyeur Beware

To go back to Iris Brey’s theory of the female gaze, the way the women protagonists are clothed is a conscious choice. In the case of Sucker Punch, it is not necessarily the way they are dressed that is important, but why, and what is made of the clothes they are wearing. The fact they are barely clothed or wearing an infantilized, literally baby doll sailor dress doesn’t automatically mean they are an object of desire. The choice of costume is compensated, not only by the irony of the choice itself, but also by the absence of graphic sex scenes, or overly sexualized dance scenes. Their appearance reflects the expectations – or fantasies – of the action movie audience.

Thanks to those numerous fight scenes, the women protagonists are allowed to act, to be subjects and not solely the objects of desire of a room full of men if they had been portrayed while dancing. By doing so, Zack Snyder shifted from the usual (although not always) voyeurist trope of women dancing in front of a crowd. He manages to shift them from objects of desire to actual subjects, bestowed with emotions and agency. Sucker Punch is not made to serve a feminist discourse, but that doesn’t mean it exists without feminist subtext or feminist interpretation.

What Zack Snyder has done – though widely misunderstood – is give humanity to the film’s protagonists in spite of events that seek to dehumanize them, reusing patriarchal and hyper-sexualized codes without reinforcing them to tell a story about those codes and the industry that produces them. Not only is this movie enjoyable thanks to its amazing soundtrack, its dynamic filming techniques, and fascinating pop-culture references, but it also created a realized female character through an asserted lack of subtlety.

Even though the movie barely lasts two hours, it provides almost endless analytical possibilities. From the use of child-like beauty standards to the deliberate lack of sex, the framework through which Sucker Punch could be analyzed was massively underutilized when it first came out. More than ten years later, many fans and other movie enthusiasts are rediscovering this movie as it was intended. The case of Zack Snyder’s Sucker Punch is truly proof that it is sometimes better to be understood later than never.

This article was first published on May 17th, 2022, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂