“CGI didn’t exist. There were no films requiring my expertise,” Tim McGovern, the veteran visual effects supervisor tells me from his home in Mumbai, India. While we have become accustomed to films featuring computer-generated images (CGI), before the ‘90s, films relied heavily on other methods to produce visual effects. McGovern’s skill set wasn’t yet compatible with Hollywood’s needs, but when the time came it would net him an Academy Award on what was only his second-ever movie credit.

After finishing his studies at the University of Chicago – Illinois, McGovern began his career working at a local camera shop, before moving into public TV stations to create opening graphics. He continued to “follow his nose” and found himself working for Robert Abel’s pioneering computer graphics company, Robert Abel & Associates.

“My first job was a United Airlines commercial showing all the routes in 3D with the planes going across the United States,” McGovern explains. “Then I worked on Tron [1982] with four other guys and I loved the sequence. It’s called ‘Flynn’s ride’ – when Flynn gets digitized and goes into the computer and becomes part of the game world. We went to the screening, the cast and crew screening. And then the credits go by and there’s my name really big on the screen. There’s nothing like seeing your name on the big screen.

“I did commercials and TV shows, and if there’s a credit, it goes by so quick. Now it’s like I can do a marathon and when I’m done with it at the end, the work will be up on the screen. And that’s part of the movie history for all time – people will be able to watch their movie 30 years from now. Commercials and TV are like fast food and now I’m going to get to make a real meal for people.”

Swing and Miss with Motion Capture

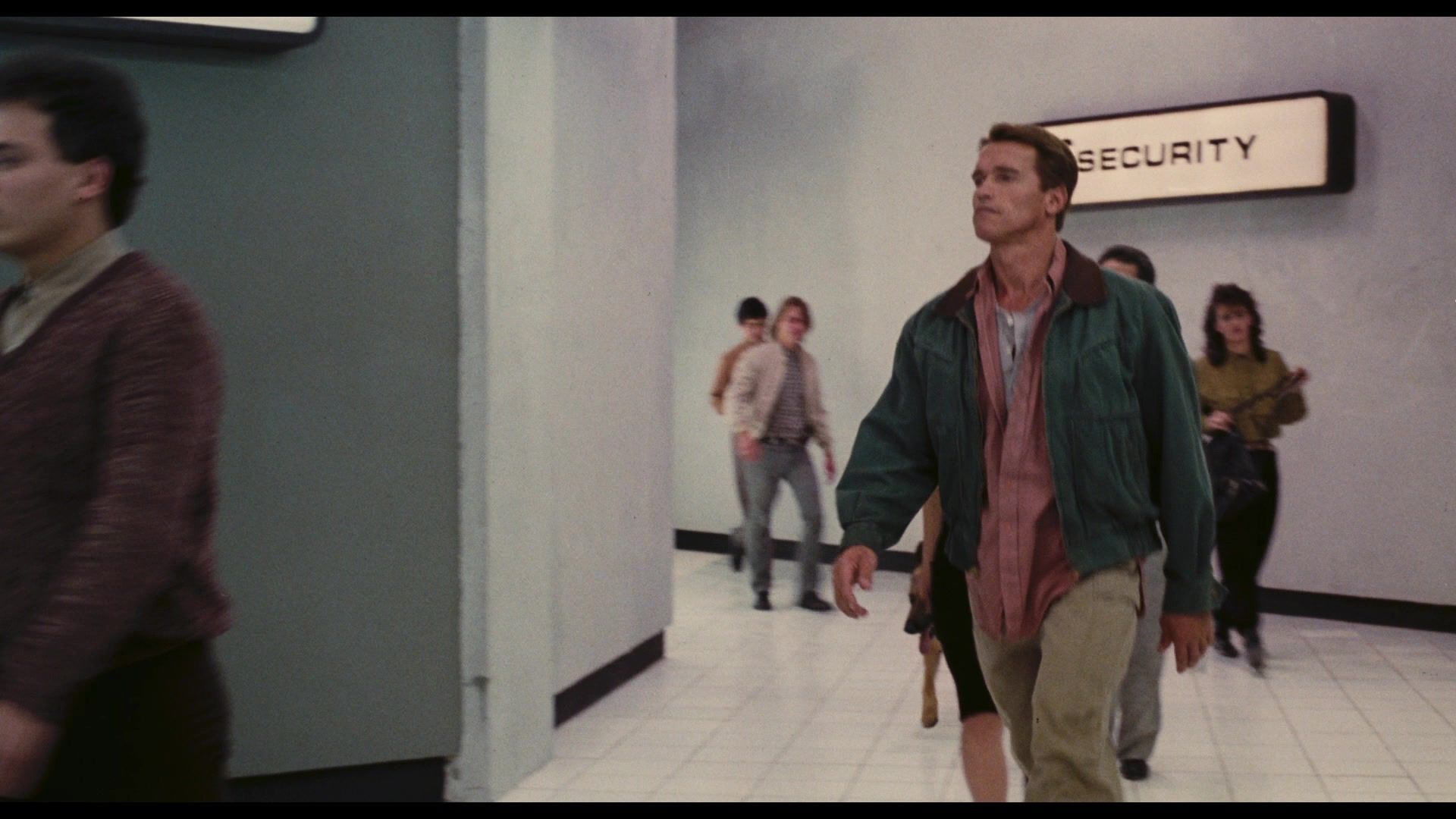

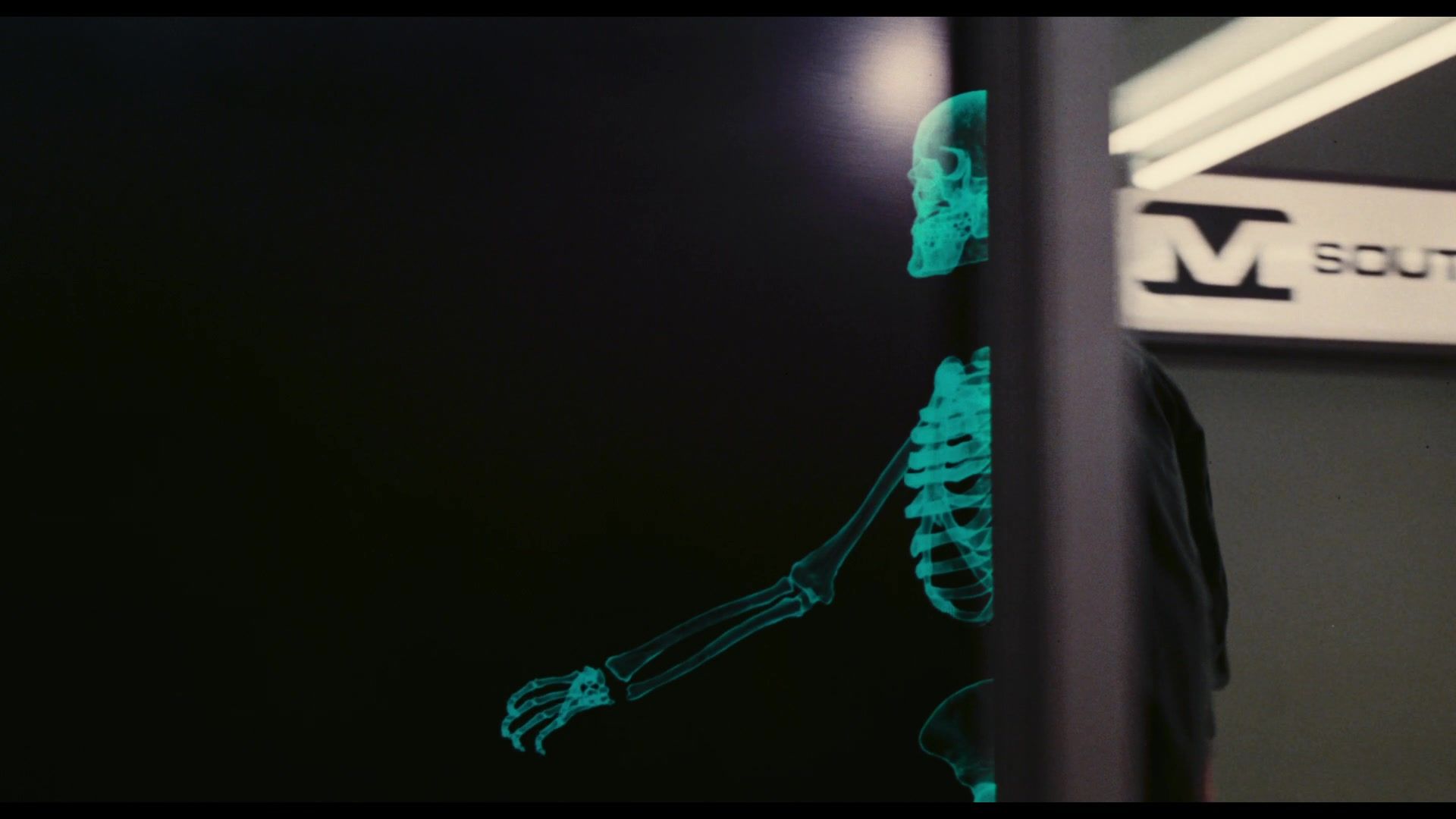

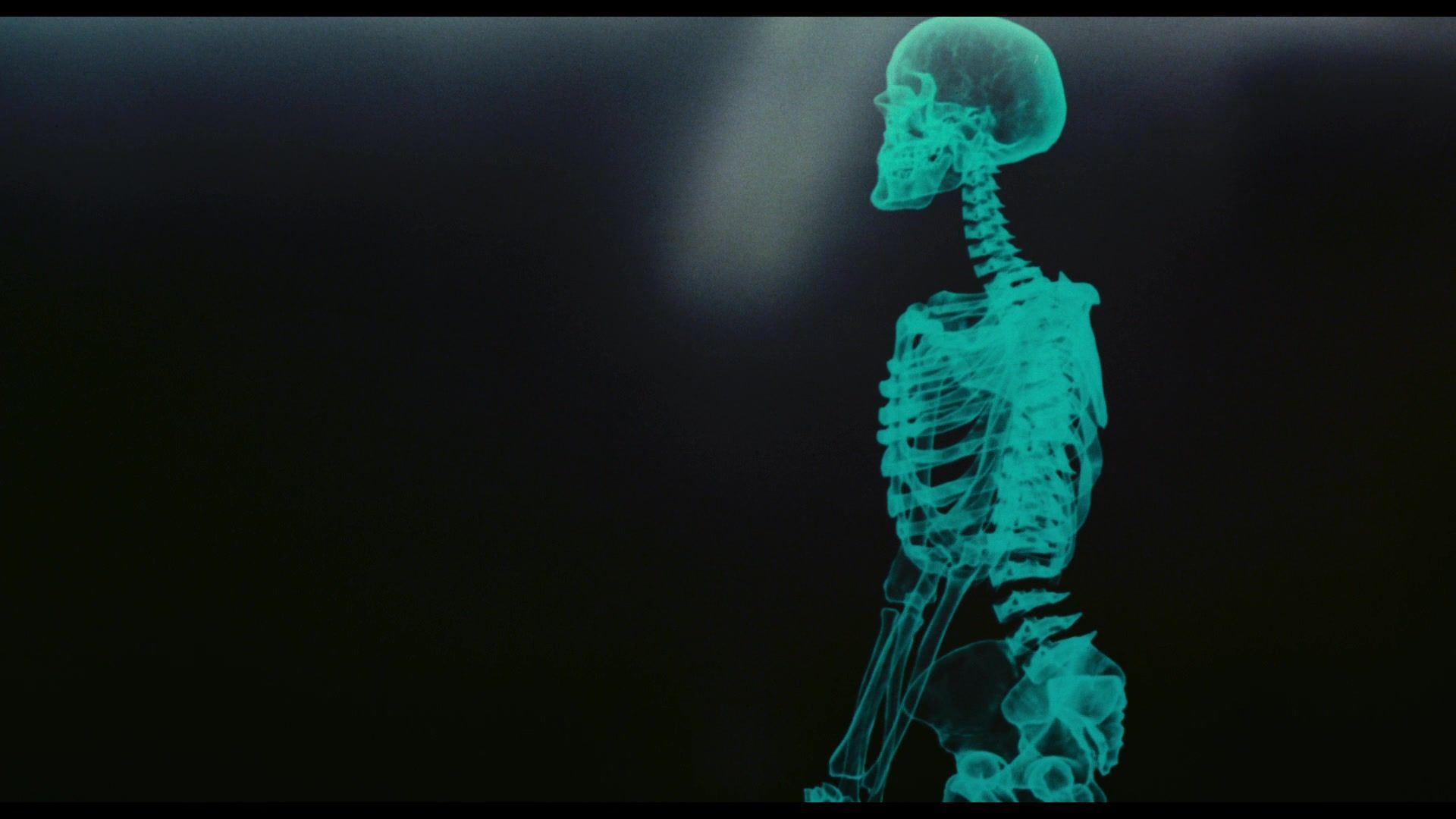

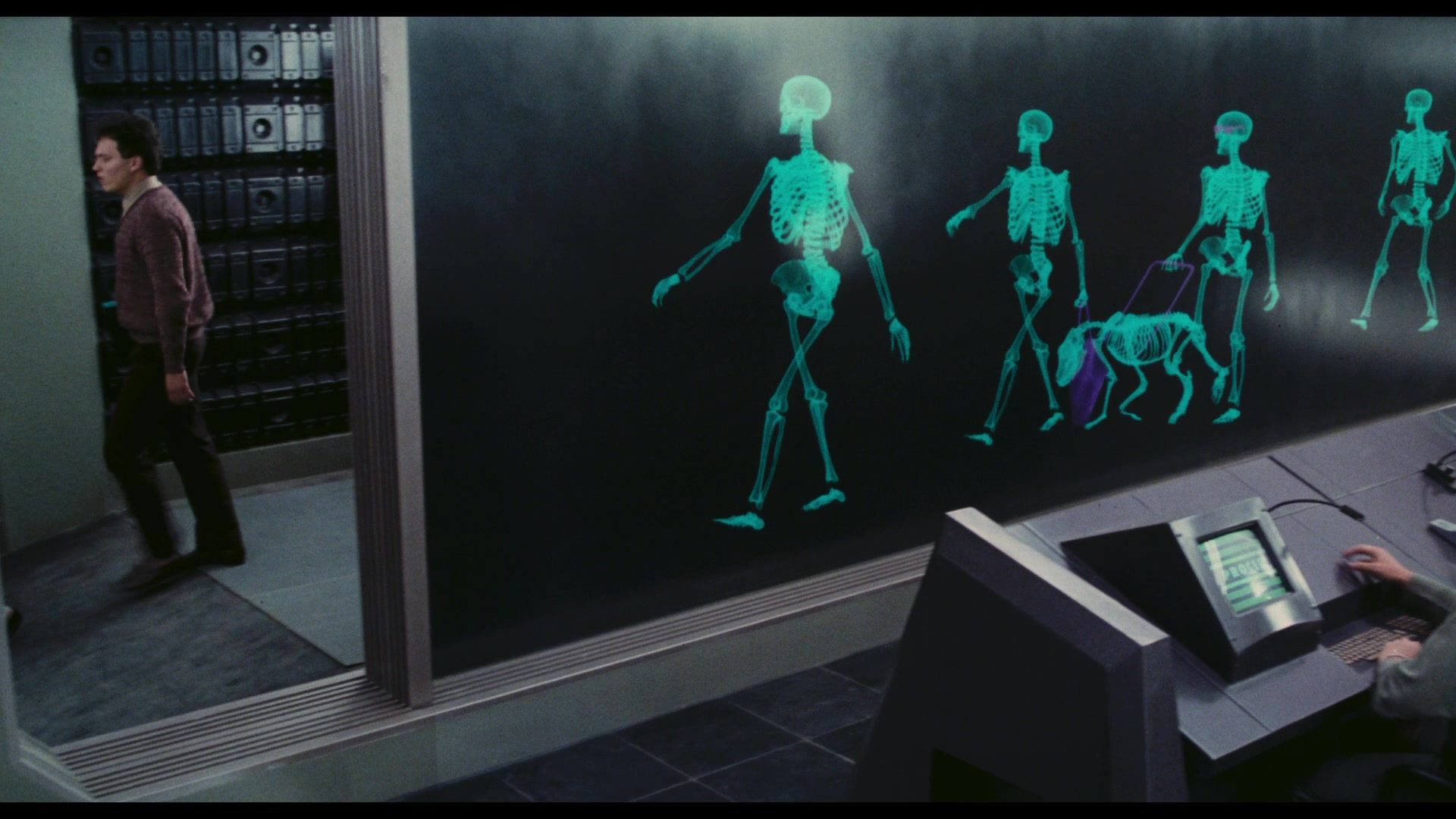

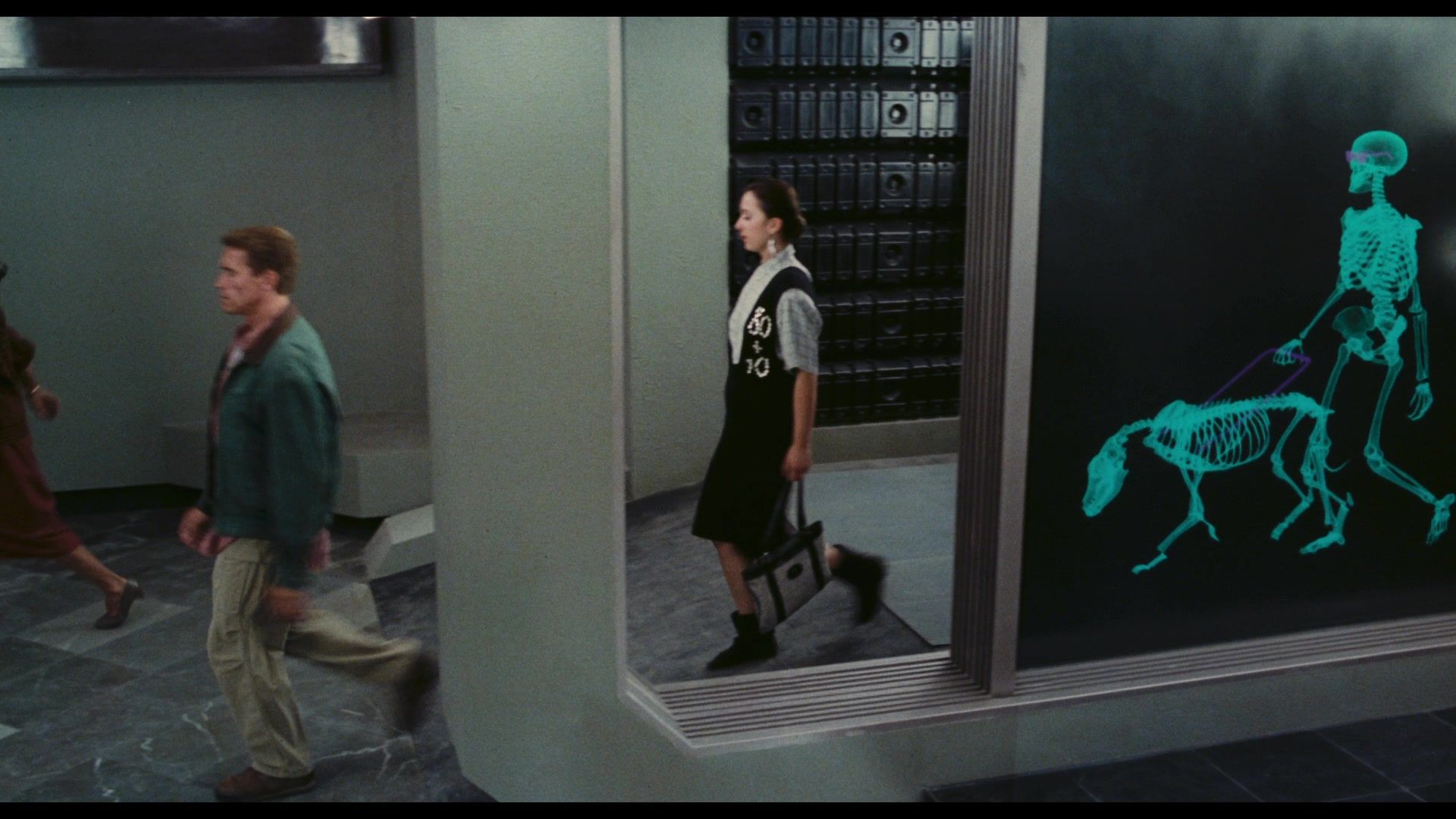

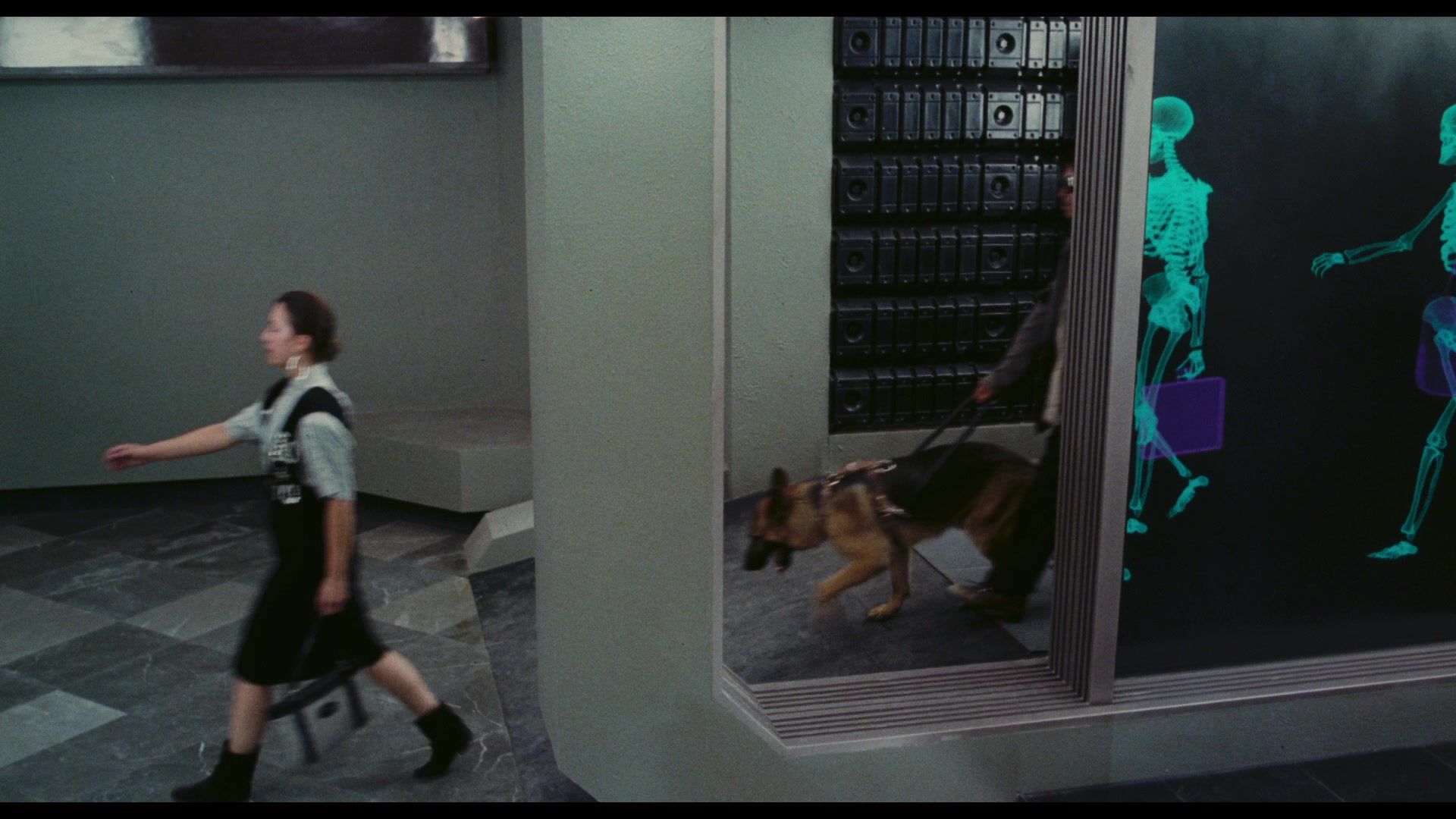

Measured in screen time, McGovern’s role as Director of CG Animation on Total Recall (1990) might have been small but the impact of the scene sent shockwaves through audiences at the time and forced the industry into a new era. In the film’s first major action sequence, the possible secret agent/possible fantasist Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) is chased through a subway X-ray machine, his holstered sidearm immediately triggering the alarm. With security closing in from both directions with their own guns drawn, the skeletal Quiad – his gun blaring a crimson alarm and his bones a lurid cyan – turns this way and that before bursting through the glass and back into flesh.

These 16 scintillating seconds are remarkable for many reasons, chiefly for their use of early motion capture in order to capture the authenticity of Schwarzenegger’s movements. This had its origins six years earlier in 1984 with a 30-second commercial for the Canned Food Information Council called ‘Brilliance’, but better known in honor of its main attraction as ‘Sexy Robot’.

“Jim Rygiel of Lord of the Rings [2001] fame was the original guy on the sequence, involved in the testing stage of it. I had done the commercial for ‘Sexy Robot’, which was featured as a Super Bowl, I was Head of Production at MetroLight and the senior technical director at the time, so I took on the sequence [when Rygiel left MetroLight].

“‘Sexy Robot’ was one of the first uses of human motion in commercials or films. It was done by meticulously rotoscoping a three-camera view of the model doing the motion that they were being directed to do, and then lining up that footage to project back on the screen of a monitor, so that we could then rotoscope and make keyframes of the segment’s body.”

Rotoscoping, which goes right back to the dawn of motion pictures, involves painstakingly painting over each frame with the sequence you want to animate. Even rendered digitally and from multiple angles as it was on Total Recall, with the technology of the day it was still a laborious undertaking.

“So that was pivotal, because the motion capture on Total Recall, as it turned out, didn’t exactly go to script. The area that Arnold had to move across within the shot required us to put the cameras quite close to him to capture his markers, which were retro-reflective balls. They were taking the light off the camera that was recording the footage. So there’s eight of them, but they made the balls really small and it looked like they were very close together.

“In those days, there weren’t a lot of experts on this, and the people who had brought the motion capture gear that was hired by the production mostly analysed people’s golf swings, which is actually kind of how motion capture got invented.”

“Golf is a multi-billion dollar sport, in terms of the revenue it generates per year. When they came to apply it, they were telling us that everything we were doing was looking great. They kept saying that when they get it back to the office after the shoot it will just compute and give us great motion.”

But as McGovern had suspected, it wasn’t going to plan. Three days after the shoot disaster struck and they were told the system couldn’t tell apart the different markers, something that could easily be fixed today. It was time for a plan B – they’d use the footage shot for motion capture, but rotoscope Schwarzenegger instead.

“Arnold was supposed to wear a black leotard [for the motion capture],” McGovern says, hiding a smile. “He was wearing white shorts and a T-shirt. I looked at Arnold and told him you’re supposed to be wearing black? Can you go back and change? But he said ‘No!’ We were fucked. However, it actually worked a charm! By doing that we could tell what the rest of his body was, you know, if we had gone with black, we wouldn’t have been able to use him to rotoscope later.”

Rotoscoping the Raw Footage

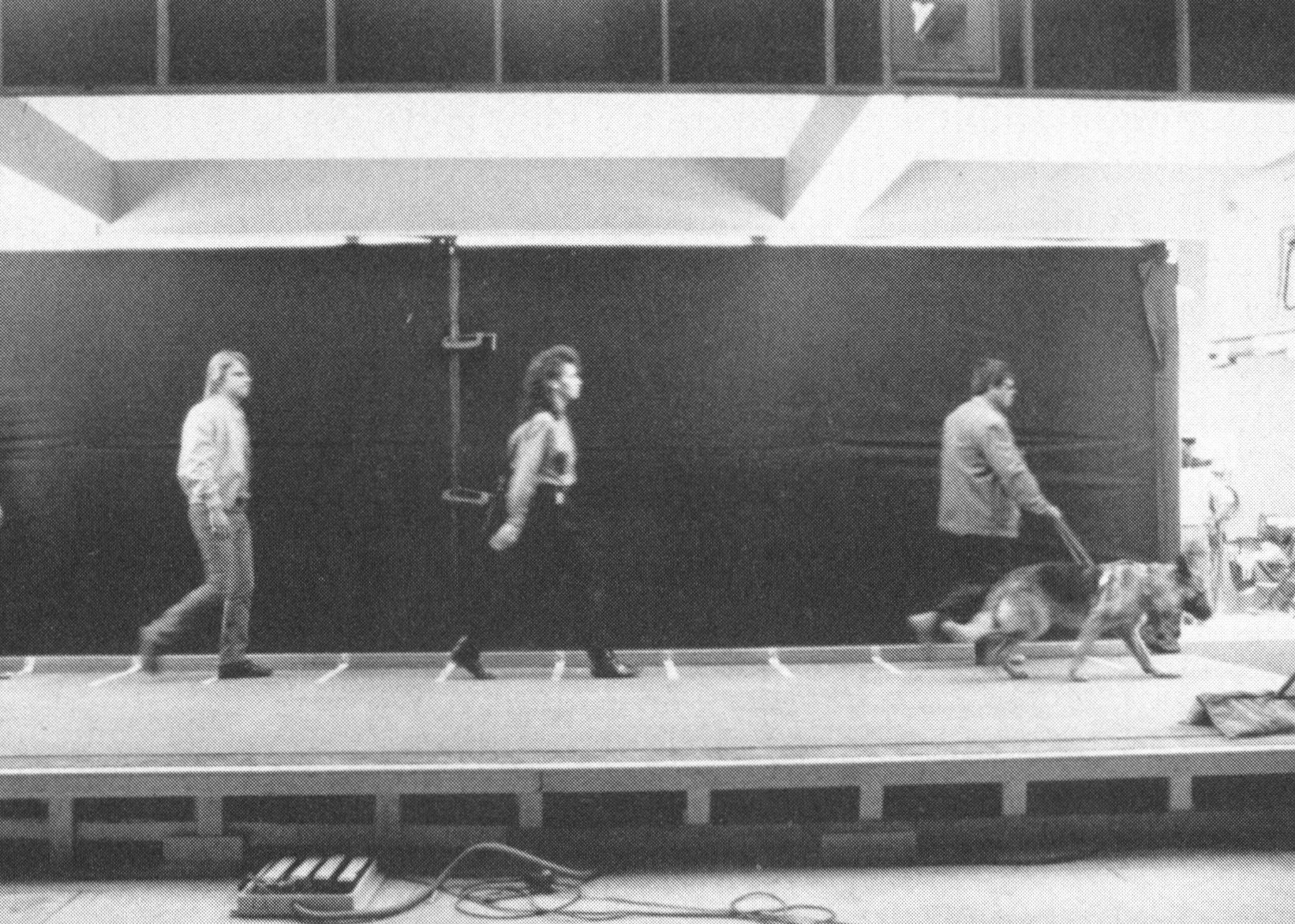

Though the complexity of Quaid’s escape required McGovern to be on set, an earlier sequence with the subway scanner was simple enough to be done remotely as Quaid mooches through as one of a line of commuters, including a blind man with his seeing-eye dog. As it was a simpler shot – no turning and racing towards the camera, just transit from left to right – these nonchalant skeletons didn’t require the dubious aid of motion capture but instead were rotoscoped from footage shot from the other side of the machine’s painted glass screen.

“This was before [McGovern’s team] were on location. So the visual effects supervisor for the movie decided to put a back-witness camera, so we could see them walking and see how they were spaced. If we had looked at the camera that was taking the shot for the scene, [we] couldn’t see through the reflective glass. So by having that we had the optimal material to work with.”

McGovern underscores just how labor-intensive even something this simple was compared to the sophisticated software available to filmmakers now.

“You couldn’t put the footage digitally behind your vector graphic of the character and skeleton. Nowadays, you do that all the time, you write on top of the footage, match things up. And it’s pixel-perfect. This, we were projecting onto the screen. We had to work in a dark room and on top of that, we had to determine what the keyframes were for every joint of the body that we had broken out for the skeleton.

“So we’re picking the start and endpoints of motion to gain midpoints. And trying to fill them in first, you could only see it from behind, they didn’t have multiple views. But actually, it was easier that only one had one camera because, from the perspective of the lens from that point of view, you can’t always know. So, the good news was we could rotoscope that from what we thought it was and then look at that as it would have been seen by the taking camera. This was just that opening couple of shots.

“We then had to go to an image transform company, so they could take this VHS footage and they were able to blow up the footage and sharpen it so we could optimize it for rotoscoping, which is what we needed to do with it. We had to get the footage transferred to LaserDisc, because this company happened to have a lot to do with creating LaserDisc as well. So by having a LaserDisc, we could at least have discrete frames that were perfect. And then we had to figure a way to get that simultaneously seen with the character that we’re animating on the screen.

“I don’t know who could have sorted that out without having had exactly the background that I had prior to this movie. It taught me how to think about this and because there was so much footage, I couldn’t do it. I had to teach a team to do it so that I could supervise them because there was far too much work for one guy to sit down.

“I used to say that making movies with visual effects back in those days was like using a chisel and stone, you know frame by frame that nothing was built to automatically use data from anywhere else.”

Creating 3D Scans of the Skeletons

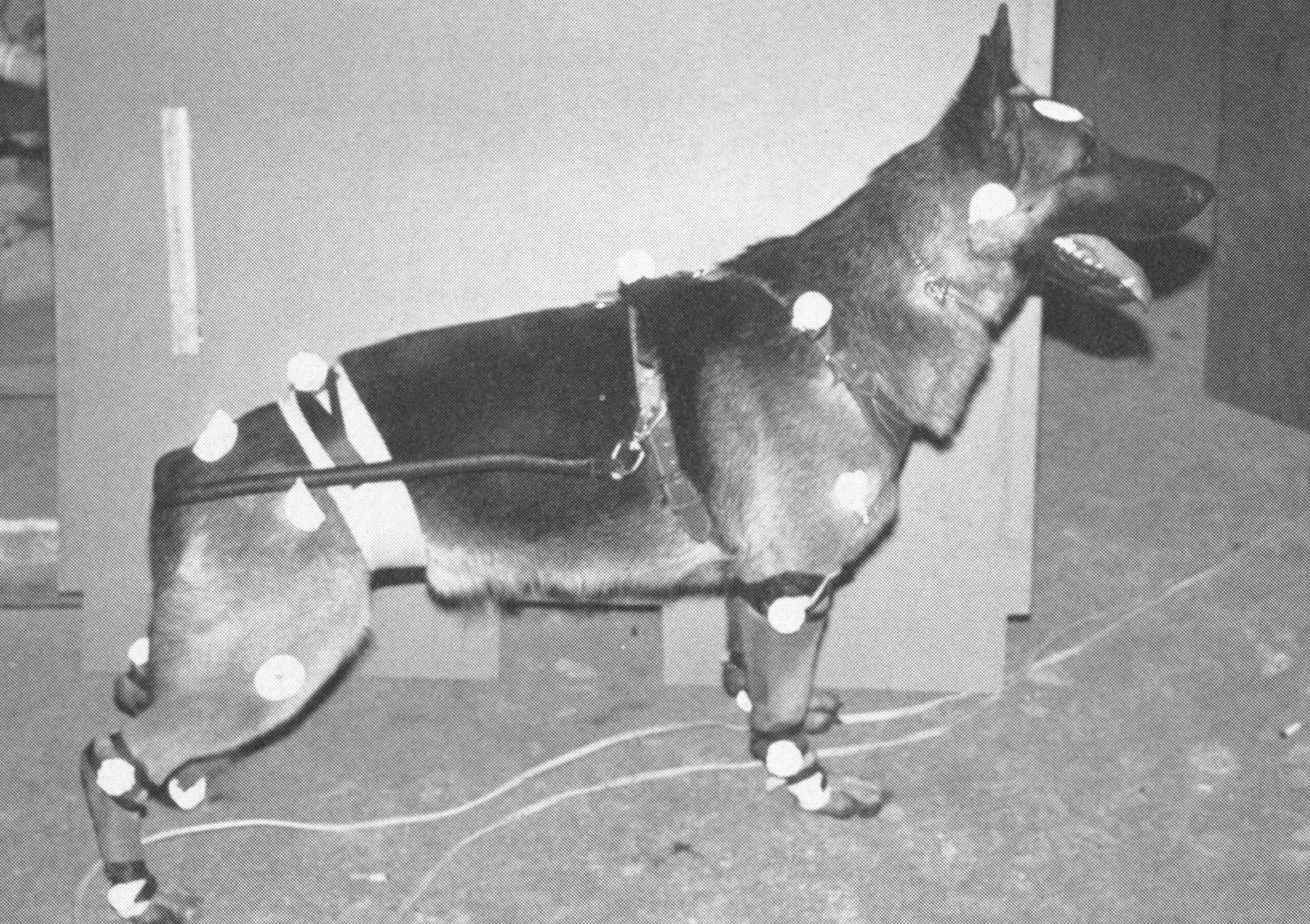

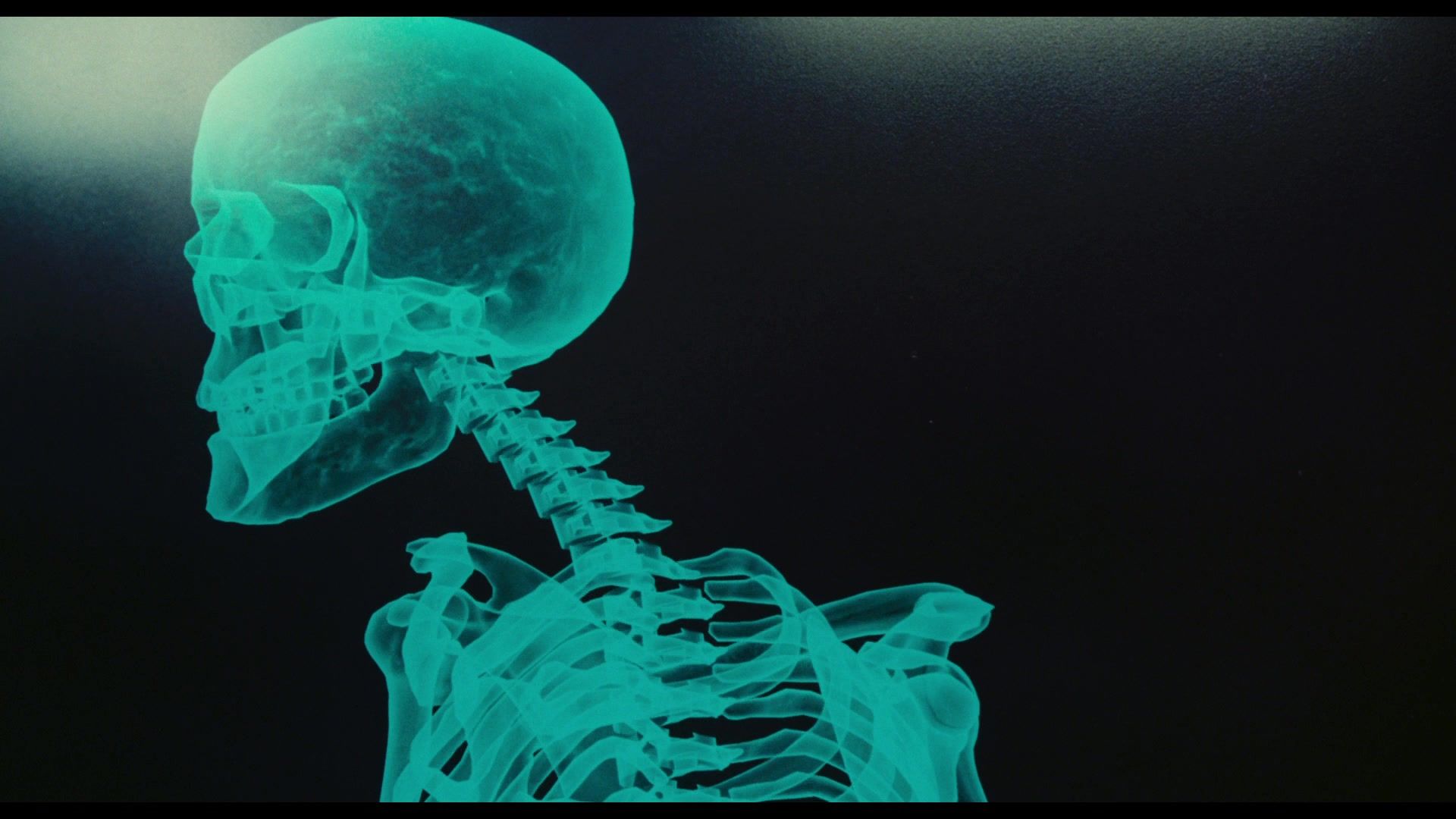

It wasn’t just that MetroLight were having to put their faith in new technology and develop new techniques, everything had to be created from scratch. These two X-ray scenes required painstaking 3D scans of the skeletal guide dog and office drones they were expected to conjure from the ether.

“We had to go about rotoscoping whatever we could, from whatever we had. In the opening shot, when you see the dog, we had to go and digitize the Dire Wolf skeleton from the LA County Museum, at the Tar Pits in LA – everything that fell into that pit over, you know, a half a million years, a million years, whatever it was, was in there.

“We had no database for a human. So we used a plastic skeleton and had to digitize both those databases because there was no such thing. The other problem to solve was how to get it to look like an X-ray. Because if it wasn’t for that, there would be no reason for them to not have stick puppets. So we had the ability to write something that did center-edge opacity, that’s what we called it, it was originally used to make glass look more opaque. When you’re looking at a sphere, you see sort of an edge around the middle of the sphere. The other thing was that the bones need to have veining in them. If you’re looking at an X-ray, the bones have like vein-like structures.

“So that’s texture and opacity mapping, but the budget wasn’t there yet, because it was being composited by Dream Quest Images. We only did the CG part of the movie and we were giving them all our elements, and they were doing the composite. We didn’t have the budget to remake the elements and my producing partner and I both looked at each other and said: ‘We need to talk to the visual effects producer on the film’. And we went to her and said that we don’t want to have worked so hard to get this motion perfect and not have it look good in the movie. We said we’d be willing to pay the money that’s going to make new elements.

“She was impressed that we cared that much and told us not to worry. Working on the film was a chance of a lifetime but there weren’t many things we could do for movies that look real enough.

“During Total Recall, I think we had half a gigabyte of storage and they cost a fortune. So to take in frame-per-frame footage, was problematic because you couldn’t get that higher resolution per frame. There was a point in time, I was sending three magnetic tape reels, one to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, one to Denver, Colorado, and one to Washington, DC, to be run on the same kind of computer that we had.

“We were buying time to render video and we needed to have all the ISO. I had to then log into those systems and download all the stuff off the tape so that we had the material to render and to work on their machine.

“We had to manage all that stuff and that limited how big anything could be anyway, and how complex any project could be. But as computers began to assist us with the ability to manage bigger and bigger levels of complexity, in addition to doing things with more and more realism. We had processors that could deal with higher levels of complexity and had more disk storage problems to solve.

“I think we had about nine guys working for five months. All we had to do was about 12 shots. We were the first effect delivered in the movie.

“Back then, they would say that CG companies were run by dreamers and liars. The dreamers would hope that something could be done and the liars would say that it could be done when we didn’t even know how to do it yet. You know, when we said we could do this, we had an idea of how we could do it, but we weren’t sure.”

Working with Arnold Schwarzenegger

Arnold Schwarzenegger, the biggest movie star in the world at the time, played a huge role in promoting Philip K. Dick’s adaptation. The former bodybuilder had already built a reputation as substantial as his frame.

“The first thing we got down there and had everything set up, you know, the props for the X-ray machine, all we had was a very simple wooden platform that had ramps either side of it,” McGovern explains.

“It wasn’t some meticulously made, you know, exact replica of the thing we had, it was another piece that had the main aspects correct. We got there and to calibrate the cameras, you needed to put up these four poles at the extremes of the area, you were going to capture the motion from all the cameras you had surrounding. That would be the reference that everything else would be derived from.

“So Arnold comes down and looks at what we’re doing while smoking a cigar wearing a hulking T-shirt in typical Schwarzenegger fashion. I look at him and realised we needed to check the height calibration because you know, he’s a big fucking guy.”

“So I said, ‘Arnold, you know, can we put you know, can we check the calibration?’ He said: ‘Sure what do you want me to do?’ and I replied: ‘Put this reflected ball on your head’ – it’s fair to say the look he gave me wasn’t one of affection. He leans down, smoking a cigar and he’s looking at me like I’m an idiot. As I’m putting this thing on his head, and he’s waiting for us to all break in the laughter or something like we’re pulling a prank, I’m sh*tting myself.

“There’s a side of you that gets fearless. When you know, if you don’t have something figured out for the whole effect, you’re gonna be screwed. Yeah. And so you get a little braver and less nervous. I was apprehensive and a little reluctant to ask him anything. But I would put this thing on his head

“Arnie said: ‘Well, what do you want me to do?’ I told him to walk back and forth on the set. In those days, they used to play a lot of pranks on set. And in that movie, they played a lot of pranks on each other. He was quite a prankster himself. So after he told me: ‘Okay, that’s good for me’. Nobody ever laughed and nobody ever brought it up again.”

Reflecting on Total Recall

It had been eight years since McGovern worked on his first credit, hardly a seasoned visual effects supervisor, but he was confident in what he helped contribute to Paul Verhoeven’s adaption of We Can Remember It For You Wholesale.

“Well, we had seen it so many times, because of all the different steps we went through and we were happy that it looked pretty darn good,” McGovern says. “When it came to picking the four names for the Academy Award shortlist, and bear in mind this movie has 1,200 shots, they said I should be on this list, even though I contributed little in comparison but because what we did was groundbreaking. I didn’t expect to be included and it was a big shock.

“But when you saw it, the whole movie and you saw that sequence, and you saw it with an audience, people actually inhaled – you could hear the inhale – when that came up the first time. And so it was groundbreaking.”

Heading into the 63rd Academy Awards, Total Recall was touted as making history. Prior to voting, Back to the Future Part III, Dick Tracy, Ghost and Total Recall (all 1990) advanced to the second stage of voting, but only Total Recall received a requisite average and it was given a special achievement Oscar. Joining McGovern to collect the award were Eric Brevig (visual effects supervisor), Alex Funke (director of miniature photography), and Rob Bottin (character visual effects).

“They were great films, but ours was groundbreaking and bigger, and more and better looking than anybody had ever done before. So it got all the votes and got an announcement the next day that we’d already won. They called me up and told me I’m getting a Special Achievement Oscar. I was part of history.”

Etched into history, Total Recall may have cost a pretty penny but the fruits of its visual-effects labor delivered an all-time classic, collecting more than $260 million worldwide back in 1990. After a nine-year break – almost a lifetime in Hollywood – McGovern returned to film six years ago when he was asked to assist on Sin City: A Dame To Kill For (2014), something that he admits didn’t take off but was “beautifully shot”.

This led to his current role as VFX Supervisor at Double Negative, based in Mumbai, where he has since worked on an abundance of features, including Mission Impossible – Rogue Nation (2015), Dunkirk (2017), Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018), and Shazam! Fury of the Gods (2023). McGovern has also penned a screenplay, using all his creativity in the bid to make an animated feature.

Even after more than 30 years, he’s still after the buzz that comes with seeing his name on the big screen.

This article was first published on November 20th, 2020, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂