Much has been written about the narrative and visual similarities between Stargate Universe and the reimagined Battlestar Galactica. These shows were developed at approximately the same time. BSG first aired in 2004 and SGU was released five years later. They, therefore, share many cultural influences from that time.

Just as Stargate Universe was a more realistic portrayal of life in space, so too does Battlestar Galactica present a more grounded portrayal of Galactica than the original BSG. Unfortunately, both shows also experienced backlash from some fans due to their change in tone. They also opened with an apocalyptic premise; the Icarus planet was blown up at the start of SGU and we witnessed the cataclysmic destruction of the twelve colonies in BSG. Finally, they both explored interpersonal relationships and were set on dilapidated vessels.

However, whilst both Stargate Universe and Battlestar Galactica interweaved religious elements into their respective narratives, their portrayals of faith and religion were dramatically different.

“Often in science fiction, we are used to getting the ‘gods are aliens’ format, which, of course, was Stargate SG-1. We’re used to getting religion as evil and being used to manipulate or hurt you,” explains Caroline Symcox, team vicar for St. Mary’s Church, Burford. “Both of these shows had religion as almost a background element, for a large portion of both shows, where it’s just there. It’s just a thing that people do and relate to.”

Polytheism and Monotheism in Battlestar Galactica and Stargate Universe

Both shows openly discussed issues around faith and religion. Whilst Stargate Universe explored faith vs pragmatism, Battlestar Galactica seemed to be more about polytheism vs monotheism.

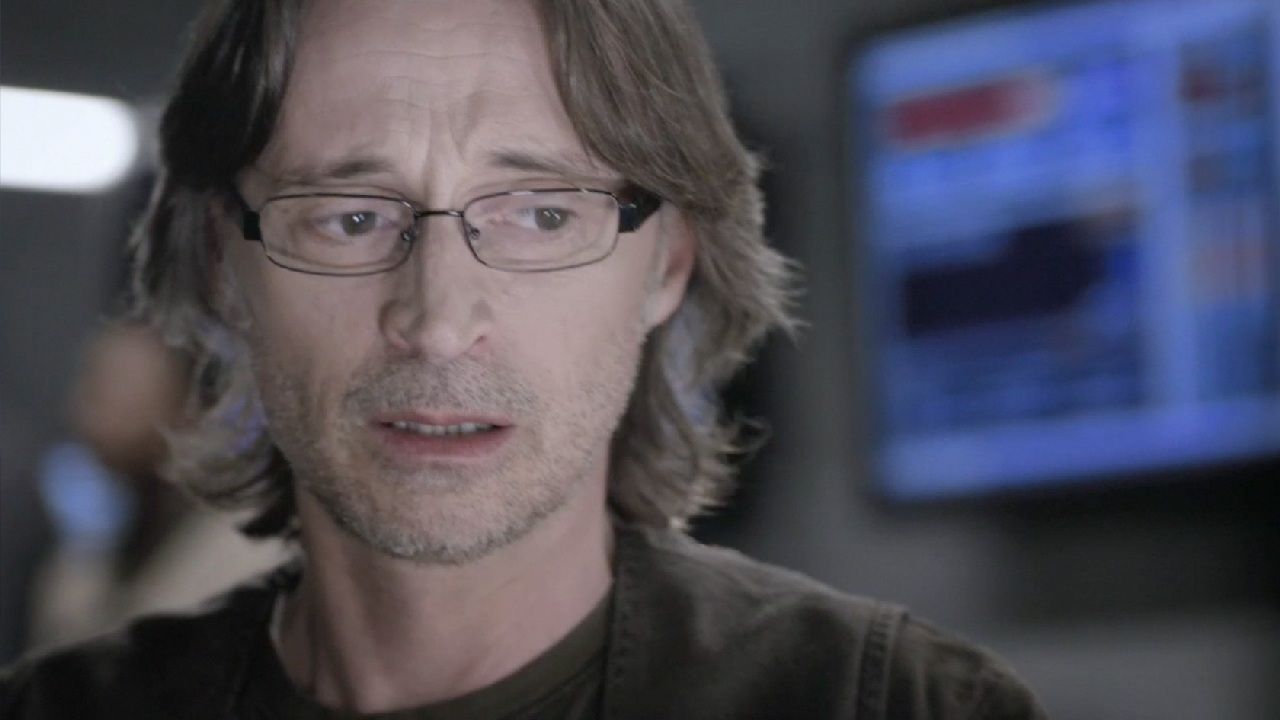

In Universe, there is a constant discussion between the pragmatism of wanting to return home and the belief that the Ancient starship Destiny is more important and therefore they should stay. This is most evident when Dr. Nicholas Rush (Robert Carlyle) is more interested in Destiny than returning home to Earth and believes that the ship’s automated systems will care for them. This fuels his recurring enmity with Colonel Everett Young (Louis Ferreira), who believes that it is his duty, as the commanding officer, to protect the crew and find a way home.

In the SGU episode ‘The Greater Good’ (S2, Ep7), Rush tells him:

“It was never about going home. It’s about getting us to where we’re going. That is the mission.”

Battlestar Galactica was focused on the polytheistic Colonial fleet and the constant threat posed by the monotheistic Cylons. In the original BSG, the Colonials’ theology was distinctly Mormon-inspired, given the influences of the creator Glen A. Larson, who came from a Mormon background. However, in the BSG remake, Ronald D. Moore evolved the Colonial’s polytheistic religion into something akin to Greek and Roman mythology.

In an interview with Beliefnet, Moore explained:

“I looked at the original series as mythos and the way it dealt with religion as sort of a global sense. I was aware that Glen had used Mormon influences and how he had created the cosmology, but I’m not that familiar with Mormon belief or practice.”

Meanwhile, the Cylons follow a singular God that has Judaeo-Christian elements. In the mini-series pilot, Number Six (Tricia Helfer) says “God is love.” This is a reference to chapter 4, verse 16 of the First Epistle of John, which states;

“And we have come to know and believe the love that God has for us. God is love; whoever abides in love abides in God, and God in him.”

Battlestar Galactica includes several references to “The one whose name cannot be spoken” as being one of the Colonials’ Lords of Kobol – an echo of the Hebrew taboo around naming God. During the final scene of BSG’s series finale, ‘Daybreak: Part 2’ (S4, Ep20), the Number Six of the future uses the word “God”, but is chastised by the Baltar of the future saying: “He doesn’t like to be called that.”

Therefore, the Cylons’ God could well be “The one whose name cannot be spoken,” but this has never been confirmed. However, this theory is not with precedent, as it is revealed in the fourth season that the lost thirteenth tribe of Kobol was an early form of Cylon. Furthermore, the Temple of Five, which was found on the algae planet, was built by the thirteenth tribe and was dedicated to the five priests who worshipped the one whose name cannot be spoken.

As Number Six notes in the Battlestar Galactica episode ‘33’ (S1, Ep1):

“God has a plan, Gaius. He has a plan for everything and everyone.”

Whilst SGU does not have a polytheistic presence, it is worth noting that in Stargate SG-1, there is of course the Goa’uld. Although they are an alien race of parasitic symbiotes, they take on the trappings of gods (predominantly Egyptian, but frequently of other mythologies too) to ensure the loyalty and servitude of their followers. The Goa’uld mimic the trappings of a polytheistic pantheon with a consistent internal hierarchy.

Contemporary faith is portrayed in SGU, albeit predominantly Western traditions such as Catholicism. The character of Matthew Scott (Brian J. Smith) is a devout Roman Catholic, who was initially going to enter the priesthood. In one of the remote camera (kino) interviews in the episode ‘Air: Part 2’ (S1, Ep2), Scott recites Psalm 23:

“I’d like to say a prayer for all of us if that’s okay… The Lord is my Shepherd. I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures. He leadeth me to still waters.”

There was a memorable moment in the SGU episode ‘Light’ (S1, Ep5) when Destiny is on a collision course with a star. After multiple attempts to divert the ship or find a suitable planet for colonizing, the crew of Destiny, in various ways, come to terms with their seemingly impending doom. Some seek solace in the company of others and some take a moment to appreciate the grandeur of space. However, another set gathered together to recite the Lord’s Prayer. It is a small moment that is not dwelled upon, but it remains a powerful image demonstrating the support that faith can offer.

“There’s something there about human hope and optimism,” says Symcox. “Not in the sense of they’re going to get out of this, but that they’re not going to tear each other apart in some kind of despairing fury.”

Biblical References in Stargate Universe

The name of Eli Wallace (David Blue) carries a certain weight. Eli is a Hebrew word, meaning ‘high’ or ‘ascent’, as well as “My God”. During the Lucian Alliance’s attack on the Icarus Base in the Stargate Universe episode ‘Air: Part 1’ (S1, Ep1), when trying to unlock the ninth chevron, Dr. Rush shouts: “Eli, Eli! I need your help.” This line is a clear reference to the opening line of Psalm 22. When Jesus was on the cross, the Bible says he cried out a line from this psalm: “Eli, Eli, Lama Sabachthani?” Translated, this means “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

Psalm 22 begins with despair but ends in triumph. The final verse of this psalm reads; “They will proclaim his righteousness to a people yet unborn – for he has done it.” This is mirrored in SGU with that scene where Rush is calling for Eli’s help. Eli is able to unlock the ninth chevron to Destiny, allowing the crew to escape the attack. This also potentially hints at the long-term vision for the crew of Destiny.

One of the most spiritual episodes of Stargate Universe is, appropriately enough, ‘Faith’ (S1, Ep13). In this episode, the crew of Destiny finds a perfect planet that should not be there. As the planet is far too young for the age of the star, they conclude it has been artificially created. Some posit that this was the work of a technologically advanced race of aliens, whilst others believe it is the work of God. This of course leads to the discussion of gods being aliens.

The planet is named Eden, which is of course a huge Biblical reference and is found to be ideal for supporting human life. A contingent of the civilian crew is led by scientist Robert Caine (Tygh Runyan) to settle there. Caine absolutely believes that the planet was created by God as a way to save the people aboard Destiny. He does not say this out of any ulterior motive; it is genuine faith:

“I believe we were brought here for a reason and that whoever created this planet will provide for us. They are our best chance of getting back home.”

“The meaning of faith is a question that’s been asked throughout the centuries. It’s as much asked in media as it is among Biblical scholars,” explains Symcox. “The way that Caine’s faith is shown, is very much a groundless faith. Out of nowhere, he suddenly sets himself up as a leader and a prophet. It’s like; this looks like it’s been designed, therefore, it’s God. There are no steps in between it’s just from one to the next immediate jump.”

Of course, naming the character Caine is a neat inversion of the Biblical character Cain. Instead of being expelled from Eden like Cain in the Bible, it is Caine who leads people from Destiny to stay on Eden.

However, Caine and the others who stayed on Eden are encountered again in SGU’s second season episode ‘Visitation’ (S2, Ep9). It is revealed through hypnosis that the people who stayed behind on Eden had been returned to Destiny to say goodbye:

Caine: I remember closing my eyes, and then we were delivered here by a greater power.

Young: The aliens who created the planet, you mean.

Caine: Or by providence.

Destiny essentially acts as an idol for some. Onboard automated systems, that no one fully understands or controls, determine the ship’s decisions, and it is up to the crew to believe that the ship will look after them. Destiny makes decisions to protect itself – and its crew – but also opens Stargates to appropriate worlds in order for them to gather necessary resources, as well as locking out worlds that pose a danger.

The Resurrection of Jeremy Franklin

Throughout SGU there are several allusions to moments within the life of Jesus. This is most evident when Jeremy Franklin (Mark Burgess) sits in the neural interface chair in the episode ‘Justice’ (S1, Ep10) – the wounds to his temples are reminiscent of Christ’s Crown of Thorns.

Cold air is pumped into the room, forcing the others to leave with the door closing behind them. The process is successful and Franklin is able to command Destiny to enter hyperspace. When the door is opened again, Franklin is no longer there. A search is immediately undertaken, but Franklin is not found.

It later becomes apparent that Franklin’s consciousness was downloaded into the ship’s memory store. Franklin is digitally resurrected by Destiny as an avatar to interact with Dr. Rush and dissuade him from trying to control Destiny by himself.

Digital afterlife and virtual resurrection are common tropes within science fiction, but the disappearance of Franklin’s body and his later return is a clear analogy to Jesus’s resurrection, where his body vanishes from the tomb. “The fact that he’s in the ship, and he can communicate as part of the ship, then that kind of is its own science fiction version of that,” says Symcox. “That notion of giving up one’s life is very much present in Stargate Universe.”

Battlestar Galactica’s Duelling Messiahs

Battlestar Galactica has two messianic characters within the show. There is Laura Roslin (Mary McDonnell), who offers physical salvation by taking on the prophesied role of the dying leader who will lead her followers to Earth. At first skeptical, Roslyn comes to accept, and ultimately fulfill, this role. “Laura is using this religious base to drive her along, but at the same time she has faith in herself,” explains Symcox. “She has some religious faith, and questions what she’s doing and how she’s using that.”

However, there is also Gaius Baltar, a scientist who abandons his atheism to embrace the Cylons’ “one true God” and becomes a cult leader offering salvation in the Cylon religion. At first, Baltar is portrayed as an unwitting collaborator of the Cylons, but through the guidance of his Number Six, he first becomes a believer in the Cylons’ God and then accepting of his role as an instrument of God’s will.

This is most apparent in the BSG episode ‘The Hand of God’ (S1, Ep10), where Baltar is forced to make a wild guess as to which part of the Tylium refinery should be targeted in order to destroy the reserves without causing radioactive fallout.

The final moment in that episode, where Baltar leans back on his balcony and gazes upwards towards the camera with his arms spread apart becomes a deeply religious symbol within the context of the show, analogous to Jesus on the cross.

Baltar: Are you telling me that God guided my finger to that target for some arcane scriptural purpose?

Number Six: You are part of God’s plan, Gaius.

Baltar: So, God wanted me to destroy the Cylon base.

Number Six: You did well. You gave yourself over to him.

Baltar: Yes, suppose I did. There’s really no other logical explanation for it. I am an instrument of God.

Roslyn’s offer of physical salvation frequently runs into direct conflict with Baltar’s spiritual salvation. Both believe the other is wrong. Roslyn sees Baltar as nothing more than a cult leader, whilst Baltar sees Roslyn as a zealot who uses faith for political gain. Yet, when taken independently of each other it could be argued that both are valid forms of belief.

However, just as Roslyn seeks to lead others to safety, Baltar’s role circumvents the religiously-fuelled conflict between the Cylons and the Colonials. Rather than saying one is right and the other is wrong, Baltar seeks to bridge the sectarian divide between the Cylons and Colonials, by offering them a different perspective.

He says in ‘The Oath’ (S4, Ep13):

“God’s not on any one side. God is a force of nature, beyond good and evil. Good and evil, we created those. We want to break the cycle. Break the cycle of birth, death, rebirth, destruction, escape, death? Well, that’s in our hands, and in our hands only. It requires a leap of faith. It requires that we live in hope, not fear.”

SGU does not lean as heavily into the messianic qualities of its characters. Colonel Young wants to lead the crew home, offering physical salvation much like Roslyn. However, this is without the religious trappings of Roslyn’s story arc. It is also worth noting that this is something that Young ultimately fails to achieve, although due to the cancellation of the series, much of the plot is unresolved. It would be interesting to see how his arc would have continued throughout the series if it had not been canceled. Would the crew of Destiny have found a way home and would he have assumed the mantle of a messiah leading his people to safety?

On the other hand, Rush is devoted to Destiny and its mission. However, Rush does not necessarily initiate others into this way of thinking. Instead, Rush behaves more like a custodian, acting as the go-between of the ship and the crew. For him, it is less of a spiritual calling and more of an intellectual pursuit.

Rush, much like Baltar, is a man of science. As we learn in Rush’s flashbacks, although he used to accompany his wife to church, Rush was not paying attention to the sermon but was focused on the equations he was working on. However, when the crew of Destiny discovers evidence of a structure buried within the background radiation, he is accepting of the concept of intelligent design. As a scientist, he can only believe in something when it is backed by verifiable evidence.

He asserts in ‘The Greater Good’ (S2, Ep7):

Young: How is that even possible?

Rush: It’s not – at least not according to our current understanding of physics, nor could we even see this structure with our technology.

Young: Okay, so what are we talking about? Some kind of code, a message?

Rush: A message, perhaps, or a sign of intelligence from the beginning of time.

“The idea that there are clues to creative purpose in the fabric of the universe is at least suggestive of monotheism, and both series leave that ultimate mystery in the background, with the question left ambiguous as to whether that one God in fact exists or not, and if so is providentially active or a distant Deistic Creator,” says Dr. James F. McGrath, Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language & Literature at Butler University.

“In SGU clues seemed to have been left, and there is an interesting element when one considers that the Ancients, seeking to solve the mystery they detected, seeded the universe with Stargates and became gods/godlike themselves.”

Similar Themes; Different Approach

Stargate Universe and Battlestar Galactica are both depictions of their respective franchises with a focus on interpersonal relationships, as well as being fantastic examples of science fiction. However, they both offer fascinating studies on our approach to faith and the impact this has on both individuals and societies.

Both shows incorporate religious elements and Judaeo-Christian references within their narratives but use them to explore different aspects of faith. SGU explores the conflict between faith and pragmatism, whilst BSG focuses on the conflict between different religious outlooks.

It has been over a decade since these shows finished and their themes remain just as pertinent today as they did then. “The nature of my faith is that it must be compatible with science; those two things cannot be at odds,” concludes Symcox. “Seeing that in science fiction, which is so often an either/or, just felt a lot more real to me. This is how real religious characters might react in those situations. And scientific ones.”

This article was first published on August 24th, 2021, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂