The Stargate SG-1 episode ‘Seth’ (S3, Ep2) is famous for Teal’c’s telling of a “Jaffa joke.” It’s memorable as the only time in all ten seasons when the usually stoic warrior – played by Chris Judge – bursts into hearty, unrestrained laughter. (The moment has been the source of many memes among Stargate SG-1 fans). But the part of the episode which stood out to me when I first watched it and stuck with me afterward was actually the remainder of the scene in which the famous Jaffa joke takes place.

Jacob Carter and Selmak (Carmen Argenziano) have come to Earth on a mission from the Tok’ra to locate the Goa’uld lord Seth (Robert Duncan), who they believe has been hiding on Earth for several millennia. They are skeptical about whether finding him is even possible. (In a scene where Jacob and Selmak talk privately with Sam Carter, we learn the real reason they came to Earth was to mend Jacob’s relationship with his son Mark.)

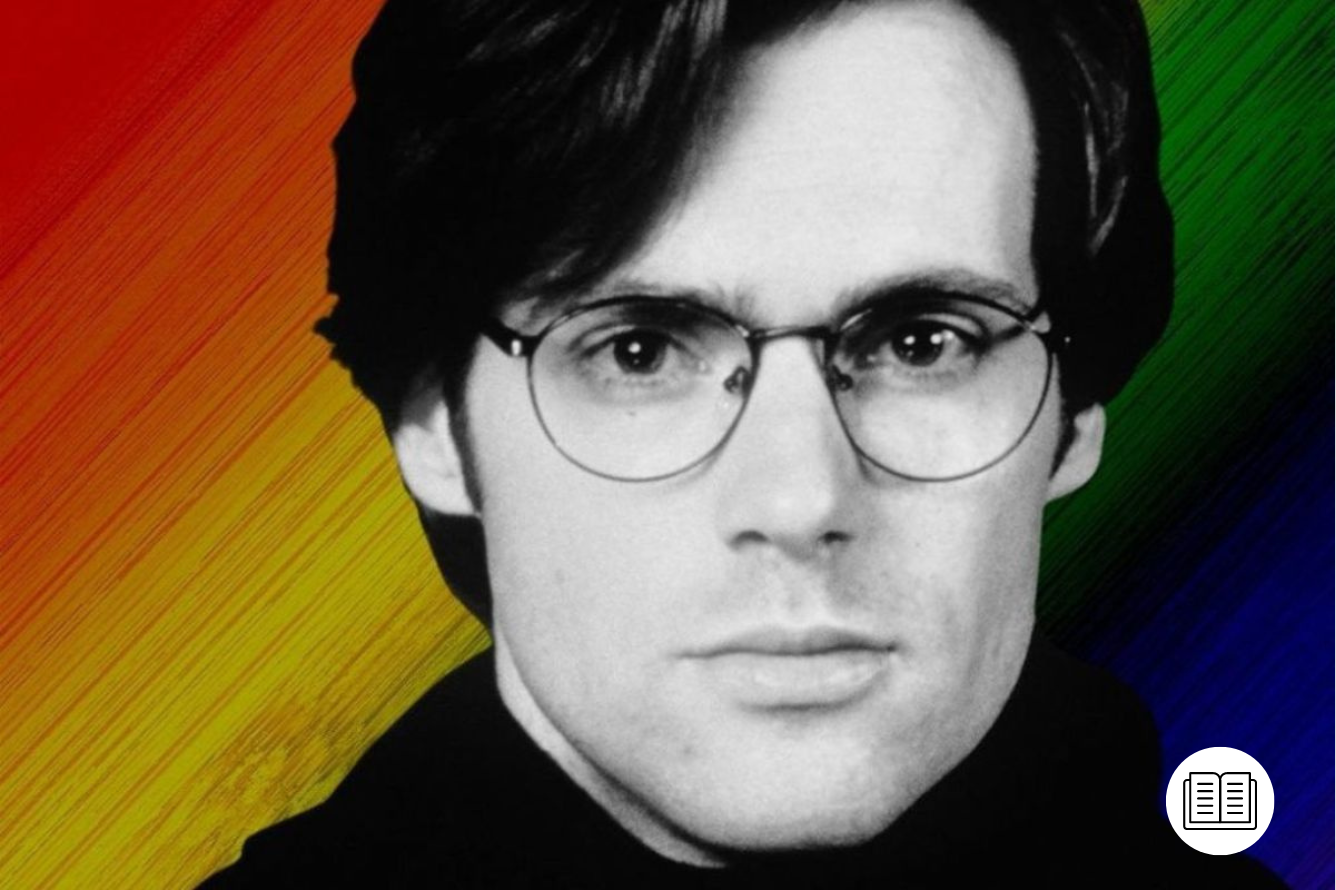

However, Daniel Jackson (Michael Shanks) is optimistic that he can track down a lead on Seth by running a few online searches. And to Jacob’s surprise, Daniel not only pinpoints Seth at multiple locations throughout Earth’s history but actually finds the exact place where Seth is currently located, enabling SG-1 to go on the mission to take him down which constitutes the rest of the episode.

The first time I saw the scene where Daniel explains how he found Seth, I realized he might fit the criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD. His capacity to think outside the box and find connections between seemingly unrelated ideas are actually both strengths that come with ADHD because the non-linear thought patterns which tend to make people with ADHD distractable or absent-minded can also work to their advantage when problem-solving.

And when Daniel demonstrated his search process, I got excited, thinking, “I can do that too!” Not the “locating Goa’uld System Lords” part, but the “finding obscure information online and putting the pieces together to reach a useful conclusion” part. It was something I did regularly in my free time, both for fun and for making more significant life decisions. It’s how I tracked down an affordable yet reliable laptop computer with enough processing power to run Adobe Premiere Pro. It’s also how several months earlier, I had discovered I demonstrated a lot of symptoms that corresponded with ADHD, and found a local specialist who tested me and diagnosed me with Inattentive-Type ADHD.

Since my diagnosis, I’d gone from excited, with an explanation for why I’d always struggled with some things, to discouraged, since even with medication, many of my struggles would never completely disappear. And they weren’t things I could just work harder at until they got easier. I’d been trying that my whole undiagnosed life up to age 23. But things like the inability to accurately perceive time (time blindness) and needing visible reminders to avoid forgetting all my obligations were simply how my brain was wired. By the time I was watching the early seasons of Stargate SG-1, I felt like any advantages from my ADHD brain were negated by all the obstacles it created when I tried to do, well, just about anything. I’d even started to wonder if I was just a permanently defective human, destined to have lots of ideas and goals but be forever frustrated as my brain kept me from succeeding at the most basic “life skills.”

But seeing Daniel Jackson make a difference by using a skill I was also good at was a turning point for me. That was the moment I realized I could still contribute something valuable to the world without changing my brain. I already had these skills, and there were meaningful processes and projects out there I could use them for. I didn’t have to keep trying to pretend I was just like everyone else in order to keep a job. Rather than always working against my brain, I could start working with it instead.

Little did I know just how significant a role his character would play in my growing understanding of my life and my brain.

Reading Daniel Jackson’s Traits as ADHD

As I continued to progress through Stargate SG-1, I noticed that Daniel Jackson and I had a lot in common. In fact, in my years of watching TV shows, I had never felt like any character so accurately represented my personality on screen – the good, the bad, and the ugly. He showed plenty of other familiar traits that came with Inattentive-Type ADHD: high distractibility, tendency to zone out during conversations, ability to hyperfocus attention on topics/activities of interest, frequently losing track of time or being late, excitedly oversharing information about topics, and impulsively making comments that were only tangentially related and not always relevant to the discussion.

Daniel’s out-of-the-box thinking and intuitive discovery of connections also continued as the show went on. It meant a lot to me that he used these skills not only for questions of language or anthropology but even for areas outside his expertise, such as helping Carter (Amanda Tapping) think through ways to work around their latest problem with an off-world Stargate. Every time he used his unique insights to help the team accomplish their mission, it reinforced for me that my own skills and intuition were useful and had value.

Watching other characters respond to Daniel provided insight as well. Whenever O’Neill (Richard Dean Anderson) got impatient and let Daniel know he was taking too long or straying off-topic, I could sympathize. People sometimes got annoyed with me for those things too. And I’d often get annoyed with myself for being unable to avoid doing them, despite my best efforts.

Yet, in the end, O’Neill still respected Daniel and came to see him as a peer and a close friend. In fact, Daniel came to be respected not just among SG-1, but by everyone at the SGC as well. His personality quirks didn’t stop people from valuing his strengths.

And it occurred to me if that’s what my quirks looked like from the outside… well, that wasn’t too bad. Nothing like I’d been afraid of all these years. Seeing myself from an external perspective, when my self-perception up to that point had been similar to a slightly warped and discolored reflection in a compact mirror, allowed me to see both my weaknesses and strengths in more accurate proportions. As a result, I started becoming less afraid of how people would perceive my neurodivergent traits, and more comfortable in my own skin.

Reading Daniel Jackson’s Traits as Autism

About six months after ‘Seth’, a comment on a social media post propelled me into a research deep-dive spanning several hours over a few days, which left me feeling like I’d downloaded the entire Ancient database of knowledge into my head. In reality, it was the beginning of a process that led to an informal diagnosis and opened up a drastically different understanding of the world around me… especially of myself. It wasn’t the knowledge of the Ancients, nor was it the location of Atlantis. But the answer did turn out to be another A-word: “Autistic.”

Cue record-scratch.

It turns out, there was another reason why I’d found Daniel Jackson eerily relatable from Day One… or more specifically, the original Stargate (1994) film. Not only did he have ADHD, but he consistently showed a number of traits that all tied back to the fact that he could also be on the autism spectrum.

I know what many people might think at this point, including myself not long ago. Me-from-the-Past might say something like, “But that can’t be true… he doesn’t act autistic. He has empathy for other people, and he studies other cultures and languages for a living. He’s known for being a diplomat and helping other people work together to solve their problems. That’s basically the opposite of every autistic person I’ve ever heard of.” (Actually, Me-from-the-Past might say “person with autism,” not knowing the majority of autistic adults prefer to be called an “autistic person,” which is why that’s considered the proper usage.)

The source of this cognitive dissonance is how most media up to this point has failed us. What people generally think of as “acting autistic” is almost entirely based on popular stereotypes from movies and TV, such as Rain Man, Good Will Hunting, BBC’s Sherlock, Sheldon Cooper, or Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Basically, a white male with genius-level proficiency in specific STEM subjects, whose social interactions diverge from cultural norms to a degree that causes significant difficulties in daily life. The stereotype often branches into two subcategories: either (1) a static character with no personality beyond his one genius trait and broad-brushed high support needs, who exists only to prompt personal growth in the other characters; or (2) a character who is the smartest person in the room but is either arrogant or innocently off-putting, correcting everyone until he learns to “be more sensitive” or earns the right to be quirky/arrogant by saving the day.

Like most stereotypes, autistic stereotypes lack realistic nuance and often cause negative real-world effects for the people they misrepresent. Diagnosed autistic people may receive inadequate accommodation and support or be denied autonomy based on how visible their support needs are. Undiagnosed autistic people may be misdiagnosed and treated for something they don’t have, or simply receive no support at all, because their autistic traits show up on the spectrum in a different way than the average clinician is familiar with. Many autistic people get all the way to college or well into adulthood before discovering why certain everyday activities and experiences have always been more difficult for them than they seem to be for everybody else.

Daniel Jackson Subverts Autistic Stereotypes

Daniel Jackson can be read as an example of a person who falls outside the stereotypes but still shows multiple traits of someone on the autism spectrum. Although his special interests don’t center around STEM subjects, the difference is really just semantics. Rather than a fascination with the laws of physics or mathematics, Daniel is fascinated by the laws of individual cultures and of human nature throughout time and space. Instead of becoming fluent in languages of computer programming like HTML, Python, and C#, he becomes fluent in languages of human speech and writing (and a couple of alien languages as well). And it’s not the inner workings of trains, robots, or rocket ships that he can never get enough of, but the inner workings of the mind, a machine that is highly predictable and yet endlessly capable of inconsistency – the product of both circumstance and free will.

But Daniel Jackson’s interest in the rules by which humans operate would have also developed partly as a means for survival. Even without his background in foster care, while growing up in a world designed by and for people with neurotypical (not autistic or ADHD) brains, Daniel would have discovered early on that he didn’t fit in. His compulsion to give accurate and complete information, black-and-white sense of fairness, tendency to be pragmatic and blunt, and wiring for a completely different set of social norms (not to mention any sensory processing differences, which can be harder to detect externally), all would have caused frequent misunderstandings and miscommunications between himself and those around him. As someone whose brain was native to a different internal “culture,” Daniel would be forced to learn the rules of neurotypical culture by trial and error (and lots of mistakes), without knowing why he didn’t intuitively grasp social norms the way most of his peers did.

With his intelligence and love for learning, it’s easy to see how Daniel would form an identity of being “the smart kid,” gravitate to academia as his parents had, and try to find a place for himself in archeology, anthropology, and linguistics – studying the topics he enjoyed with others who enjoyed them too. But the introduction of his character in the Stargate movie shows how that plan fell apart. Though by that time he’s learned how to conform enough to get by, he still can’t deny his fundamental need to understand and accurately represent reality, no matter how unpopular or far-fetched the truth may seem to others. The rest of the movie shows his gradual shift from survival by accommodating others to achieving fuller autonomy: joining the first mission through the Stargate, making his own decisions about what’s right or wrong, challenging authority, and ultimately deciding to make his home on the planet Abydos with his new wife and her people.

The pilot episode of Stargate SG-1, 'Children of the Gods' (S1, Ep1), upends the new home and family Daniel has created for himself, in a place where everyone expected him to be “different” and accepted him that way. Back at the newly-established Stargate Command, Daniel finds himself once again inside a system with cultural norms that are foreign to him, and sometimes go against the grain of his nature. This time, instead of trying and failing to conform, he takes the opposite approach. He continues to exercise his autonomy, using logic and persistence to push through the rejection he’s partially come to expect.

Even after Daniel proves his value and more than earns his place on SG-1 over the next few seasons, there’s a part of him that’s never fully at home. In Season 3, his initial instinct after the death of his wife, Sha’re, is to want to pack up and leave SG-1 and the Stargate program for good, returning to the comforting familiarity of an Egyptian archeological dig instead of accepting comfort from his friends. Later in the Stargate SG-1 episode ‘Shades of Grey’ (S3, Ep18), when Jack O’Neill is running a covert op within SGC and pretends to go rogue, Daniel insightfully thinks there must be a reasonable explanation for why his friend appears to suddenly turn to the dark side. Sensing that Daniel might blow his cover, O’Neill throws him off the scent in a move he later apologizes for, by intentionally triggering Daniel’s deep fear of rejection from someone he has opened up to. In the face of apparent betrayal, a few sentences are enough to convince Daniel that the past few years of their friendship could have all been a lie.

Although they repair their relationship after the op is complete, that moment shows how the foundations of Daniel’s relationships remain precarious atop the lie he most fears to be true. It’s the same lie he wrestles with in the hours leading up to his death/ascension in the Stargate SG-1 episode ‘Meridian’ (S5, Ep21): that he is still not enough to be worthy of acceptance and love as he is.

Daniel: You said I was the only one qualified to judge myself. So no matter how much I want to achieve enlightenment, or whatever you call it, what happens if I look at my life and I don’t honestly believe I deserve it?

Oma: The success or failure of your deeds does not add up to the sum of your life. Your spirit cannot be weighed. Judge yourself by the intention of your actions, and by the strength with which you faced challenges that have stood in your way.

Daniel Jackson Learns to Love Himself (and So Should You)

But in Stargate SG-1 Season 7, after Daniel returns from ascension, we see a fundamental change in him that continues to develop throughout the last four seasons. Overall, he seems more confident and secure in himself than before. He does what he’s going to do without feeling the need to defend his reasoning, and says what he thinks without trying to persuade others to agree. His relationships undergo a qualitative shift, and his friendship with Jack O’Neill specifically takes on a new level of trust where before there was defensiveness and occasional culture clashes between militarism and humanism. After a harrowing encounter with the Ori at the start of Stargate SG-1 Season 9, Daniel voluntarily confides in O’Neill in a way that makes him vulnerable – something he would never have done under the same circumstances in earlier seasons.

The Stargate SG-1 episode ‘Orpheus’ (S7, Ep4) provides insight into the change. It’s another episode I enjoy not just for itself, but for what it means to me personally. While Teal’c is wrestling with the fact that he no longer has the same rapid healing or (in his mind) the same strength as when he possessed a symbiote, Daniel is wrestling with the question of whether he could be doing more good if he were still an ascended being.

Teal’c’s struggle resembles my previous fears that I was permanently deficient and incapable of functioning or accomplishing anything in my life. As he and I both learned, we may have real limitations we never expected to be living with, but there are still plenty of things we can do to adapt to our limits and maximize our strengths.

And the question Daniel asks about his ascension throughout the episode is the same question I used to ask about my brain: Would my life be better and more meaningful if things were different? If I were different?

In the end, after their latest mission is complete and they’ve returned to SGC, Teal’c, and Daniel meet in Teal’c’s quarters to meditate. Before they begin, Teal’c reflects on how he has come to accept his new physical state. Daniel tells Teal’c he’s made a discovery of his own through their recent experiences. He says:

“I used to feel like I didn’t belong… anywhere, really. I think I thought that this whole ascension thing would change that. And now I’m realizing, the sacrifices were far too great. My life here is too important to just leave behind. I guess what I’m trying to say is that, for the first time in my life, I feel like I’m a part of something. Something important.”

The most important thing I’ve learned from Daniel Jackson is the same thing he discovered: that he didn’t need to change or become someone else in order to make a difference. He didn’t have to conform perfectly to social norms or prove himself worthy of respect and acceptance despite his limitations. Being autistic and/or ADHD, with whatever specific traits that entail for a person, is just as legitimate a way of being in the world as being neurotypical… full stop.

And as Daniel learns to accept and respect himself as-is, he also gains the freedom to be vulnerable and take greater risks in his relationships. His identity is more secure, allowing him to accept the love of his friends and love them better in return, without fear that one day a failure in their love may confirm him to be unworthy of love. After years of searching, Daniel has finally found a place where he belongs… but he had to stop running from himself before he could truly take part in that belonging.

As for me, even with my own difficulties understanding or predicting what other people are thinking, sensory processing overloads, limited attention span, insomnia, surprisingly frequent word recall issues, and the rest of the constellation of traits that make up my experience of autism and ADHD… I wouldn’t change my brain if given the chance. Doing so would also take away all the parts of myself I’ve come to value: the strengths, insights, and experience of the world I can only get because I’m neurodivergent. The sacrifices would be far too great. And the people in my life who already accept and love me the way I am, and have helped me grow in my ability to love other people, are too important to just leave behind.

Now, as I work toward becoming an advocate for disability inclusion – something my neurodivergent brain has uniquely equipped me to do – I look back and feel immensely grateful for my journey to this point. Because, for the first time in my life, I too feel like I’m a part of something. Something important.

And I’m kind of excited.

This article was first published on August 31st, 2021, on the original Companion website.