Bill McCay is a “heretic”. At least, he thinks people might call him that if they’ve read any of his Stargate novels.

“If you’re looking at Amazon, you see people saying, ‘How the hell does this clown get to do these books? They don’t have anything to do with the TV series!’” McCay says with good humor during a Zoom interview.

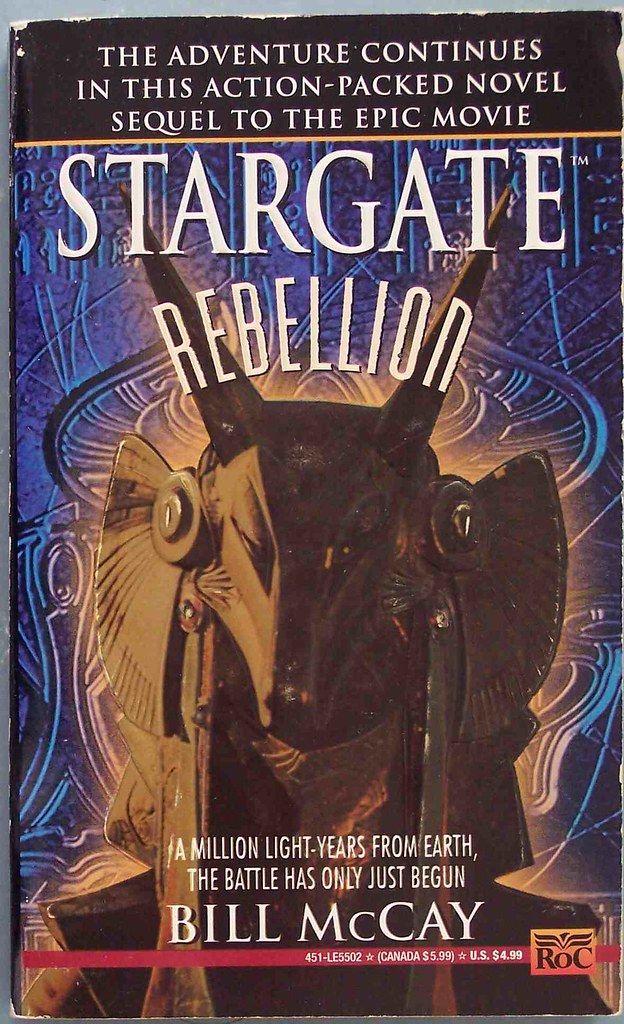

In his long career in publishing and writing, McCay has written over 100 books, including film and TV tie-ins for properties that include Tom Clancy’s Net Force, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Zorro, and Young Indiana Jones. His Stargate titles – Stargate: Rebellion (1995), Stargate: Retaliation (1996), Stargate: Retribution (1997), Stargate: Reconnaissance (1998), and Stargate: Resistance (1999) – was published by Roc in the 1990s.

As it has now been over two decades since McCay’s Stargate books were released, you’ll have to hunt through thrift stores and second-hand bookshops to find one. If you succeed, however, you can be forgiven for being confused after the first few pages. In McCay’s Stargate universe Samantha Carter, Teal’c, and Apophis are absent, Sha’re is Sha’uri and breaks up with Daniel Jackson, the Stargate program becomes public knowledge, and in the text (although not in the publisher’s back cover synopses), the titular noun is written as StarGate, not Stargate.

Still, anyone familiar with the finer details of the franchise’s metamorphosis from feature film into small screen saga will know there is a good reason why McCay’s stories don’t conform to canon.

“There are occasionally some intelligent people who say, ‘Did you look at the dates on the books? They predate the show’,” McCay jokes.

Put another way, McCay’s universe came first. He was commissioned to write novels that continued the story of the 1994 Stargate movie (or, more accurately, its novelization). His stories were the first expansion of the concept Dean Devlin and Roland Emmerich created. Given this, heretic hardly seems like a fair label for someone who was, in a sense, one of the founding fathers of the franchise.

How Bill McCay Got His Start

After leaving Fordham University in his hometown of New York City, McCay had to work his way through a variety of jobs before he had enough experience to support himself by writing books.

“I started out as a Brooklyn kid and quickly wound up in beautiful Queens,” he explains. “I grew up reading a lot and wanted to tell stories. I came out of college with a really useful double major in English and Theater, which I attempted to put to use working in public relations. I had several miserable years doing that.”

McCay’s next step up the writing ladder involved getting in “on the ground floor” with the editor of a magazine that went in weekend editions of newspapers. Although the job didn’t look like much at first, it would allow him to hone skills that would serve him well as an author. Also, it started with what he describes as “the greatest interview I ever had.”

“I came to the address expecting an office and finding a four-story brownstone, where I got to run up the stairs in my three-piece suit,” McCay recalls. “The person who met me at the door looked like they had spent the time I was running up the stairs getting dressed and getting out of bed. Essentially, I handed her my resume and she said, ‘Did you type this?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ She said, ‘Good. There’s a typewriter over there. I need a letter.’ Over the course of several months, she would say to me, ‘Geez, I need something proofread. Do you do proofreading?’ [I said,] ‘Yeah,’ [and she said,] ‘Okay, I need something copy-edited. Have you done copy editing?’ [I said,] ‘Yeah,’ [so she said,] ‘Good. I need about six column inches of story here where I’m short. Could you write something?’ … By the end of that adventure, I was working for her freelance as a researcher and occasionally writing.”

When McCay’s employer moved to another company and found herself without an associate editor, she hired McCay again and he held that position until she left and he “wore out his welcome”. His next job, however, would help to establish him as a novelist and give him a new title.

“My friend said, ‘I just started a book packaging company [Megabooks] and I need book product to sell. Can you write me a novel?’” McCay explains. “So, I wrote a novel and she sold a 12-book series out of that and that was the beginning of her company. I would come in and do freelance stuff for them until finally they had enough and they asked if I would come into the office and work. I said, ‘Sure, why not?’

“It was two female partners and they would go out on sales expeditions … They finally said to me, ‘Look, you need a title because we go in and say, “I am the President, this is the Vice President and this is Bill.” I said, ‘Well, King of Albania is vacant.’ I figured if I go for a title, I should go for something interesting. They said, ‘No, no, something publishing-related.’ I said, ‘Count of Monte Cristo?’ They said, ‘We were thinking Editor-in-Chief.’

“My father had an old joke. The joke is that the managing editor of a newspaper decides he is going to prove his chops and that he still has what it takes. He goes off as a foreign correspondent to the war in cannibal land and, of course, he winds up in the big iron pot.

“The king of the cannibals, educated in Oxford, comes over and says, ‘Well, old boy, what were you before you became lunch?’ And the fellow replies, ‘I was a newspaperman. In fact, I was a managing editor.’ And the king replies, ‘Well, look at it this way, after lunch, you’ll be editor-in-chief.’ Whenever I have met an Editor-in-Chief, this is what has always gone through my head so that I have a very healthy unwillingness to take these people seriously.”

Many of McCay’s books from this period will be hard for the casual reader to identify because they were written under pseudonyms.

“When I started out I was the spirit behind a whole lot of house names,” McCay says. “That was book packaging. The idea was that we’d have a bunch of people doing the books, and if we wanted them to be on the same shelf in the bookstores, we invented names. I started out as J.J. Fortune. That was the first.”

A web search for the name ‘J.J. Fortune’ will bring up the Race Against Time novels. Published in the 1980s, these adventure novels for young readers were typical of the work McCay was doing at Megabooks. In a 2002 interview for a fan website dedicated to The Three Investigators, another book series he contributed to, McCay explains that as head editor at Megabooks, he was responsible for several Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew stories, too.

“Megabooks specialized in series for children and young adults,” McCay told the site’s interviewer, Seth T. Smolinske. “I wrote and edited a lot of books under a variety of pseudonyms and ‘house names’ … [i.e. – Franklin W. Dixon, Carolyn Keene, Victor Appleton, etc.]. Along the line I was involved with several well-known series: The Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew, and The Hardy Boys… Along with the editing job, I was trying to write at least two books a year. I understand the cat is pretty much out of the bag on my participation in another old-time series, Tom Swift.”

It took about 10 years before McCay could get a book published under his name, he tells us. Even then, however, different versions of it appeared on different books and sometimes even on different editions of the same book. For example, the Star Trek: The Next Generation novel Chains of Command, which was originally published in 1992, can be found with him credited as ‘W.A. McCay’ on some copies and as ‘Bill McCay’ on others.

“Well, there’s an ongoing joke about that, which one of my editors coined, which is, ‘If I liked the book, it’s Bill, but if I think the book is not as good as it could be, it’s William,’” McCay jokes.

Stargate: Rebellion and Establishing the Series

Early in the 1990s, McCay was commissioned by Roc to write a series of books based on a concept credited to comics legend, Stan Lee. Stan Lee’s Riftworld series was a blend of sci-fi action and humor about a comic book artist who manipulates an interdimensional wormhole to bring giant superheroes to Earth. McCay shared the writing credit with Lee on one book, Odyssey (1996), but was exclusively credited on the cover of two other titles in the trilogy, Crossover (1993), and Villains (1994).

In the period during which these books were published, the Stargate (1994) feature film was released alongside a novelization that was credited to Devlin and Emmerich (although some sources say it was ghost-written by Stephen Molstad, author of the paperback adaptation of Independence Day). When Roc was looking for a writer to continue the Stargate story in print, they turned to McCay because of Riftworld.

“I had done that for Roc Books and Amy Stout, the editor there, thought that the Stargate novels would need a bit of humor as well as adventure and asked me if I could do that,” McCay recalls. “Because I had written her a comedy adventure series, she figured I should be able to do this as well. So, that was just dumb luck. I had done another project beforehand, [and] the editor liked my work and asked if I would do some more of it. So, like most of the good things that happened to me in this career, I fell into it.”

McCay’s first Stargate novel, Stargate: Rebellion, was published in October 1995. ‘The adventure continues in this action-packed sequel to the epic movie’ declared the headline above the title on the front cover. Strictly speaking, though, the book was a sequel to the movie’s novelization rather than the movie itself, McCay explains.

“Use the novelization as your Bible, that’s what they told me,” he remembers. “I believe it’s in the novelization of the movie, that [Colonel O’Neil] is referred to as a Marine, but the way he was dressed in the movie, my Marine friends said he looked like Air Force Special Forces. It was like, well, I’ll go with the book because that’s sort of what I was told. So, he became a Marine.”

Switching O’Neil’s armed forces allegiance did have its advantages for McCay, however, as he had a reliable source who could fact-check his writing.

“I had a writing buddy, an ex-Marine, who read the book and said, ‘It’s pretty good but you know you’re using terminology that military people really wouldn’t use…’ He said, ‘We never even refer to gunfire.’ I actually took him on as an advisor so as not to do stupid things in the second one and in the rest of the series.”

The plot of Stargate: Rebellion revolves around the aftermath of Ra’s death in the movie and the impacts that freedom has on the inhabitants of Abydos. Unfortunately, these are not all good. Whether intentionally or not, McCay’s story can be seen as an allegory for rich nations in the real world exploiting poorer nations’ access to valuable resources. Earth, and more specifically the American government, sanctions a mining company’s attempt to profit from the mineral resources the Abydans (officially named Abydonians in Stargate SG-1) collected for Ra (this was called naquadah in the series but isn’t named in the book).

Although this initially looks like a good economic opportunity for the Abydans, the corporation’s overzealous managers, supported by the American military, impose unreasonable production targets on the Abydans and derisively refer to them as “Abbadabbas”. Naturally, this doesn’t go down well with the locals, leading to conflict and tacit social commentary. Although there was plenty of action, the publishers were concerned about the optics, McCay remembers.

“The first book I just sort of wrote on my own,” he says. “I guess the only thing they said was, ‘Well, if you’re going to be depending on the military to save the planet, you’re really going to have to soften it,’ [because] they come off very poorly in the first book.”