Let’s not forget, as we begin on what could be an esoteric and convoluted journey, that Ra was not originally going to be an alien in the Stargate (1994) movie.

Jaye Davidson’s character was an Egyptian working for extra-terrestrial overlords before co-writers Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin decided to change his origin story while in the car together.

“He was the boss of the humans, but he was still slave to the aliens,” Devlin told Variety in 2019. “We messed with his voice and made his eyes glow. We did all these things to make him scarier and more intimidating.”

It’s important to remember this because so much of the ancient aliens (or ancient astronauts) philosophy – that is the belief that extra-terrestrials are our ancestors and did everything from building the pyramids to creating the human race – influences and is reflected back by whatever elements of popular culture are, well, popular at the time.

“There’s this constant back and forth between the literature, the discourse, and popular culture,” says Dr. Frederic Krueger, a highly-regarded Egyptologist and author of perhaps the only academic journal article Companion subscribers must read, The Stargate Simulacrum: Ancient Egypt, Ancient Aliens and Postmodern Dynamics of Occulture. “They make a big, splashy version of these stories and then this starts to influence the discourse.”

In other words, it’s all one big, beautiful laundry drum of ideas and contentions, theories and responses, tumbling round and round inexorably. And it’s also why Stargate – both the film and the subsequent series, Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, and Stargate Universe – have become such a fundamental part of the ancient alien mythos, whether they meant to or not.

In an early interview to promote Stargate SG-1 with Starlog No. 242 (September 1997), co-creator Brad Wright echoed the guiding philosophy underpinning the conspiracy theory with reference to examples that have long littered ancient alien literature:

“The race to which Ra belongs took the form of many different alien cultures, way back in our history. So, we may go back to a planet where there are ancient Norse cultures, one populated by ancient Easter Islanders…”

Similarly, co-creator Jonathan Glassner enthused in the pages of Cinefantastique Vol 29 No. 2 (August 1997):

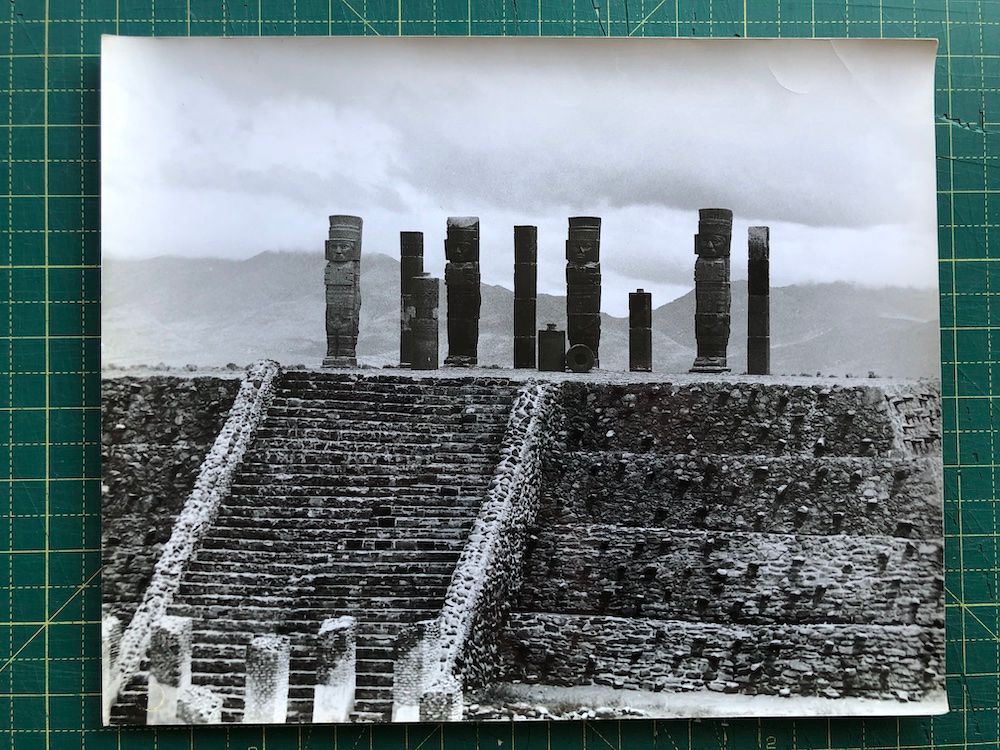

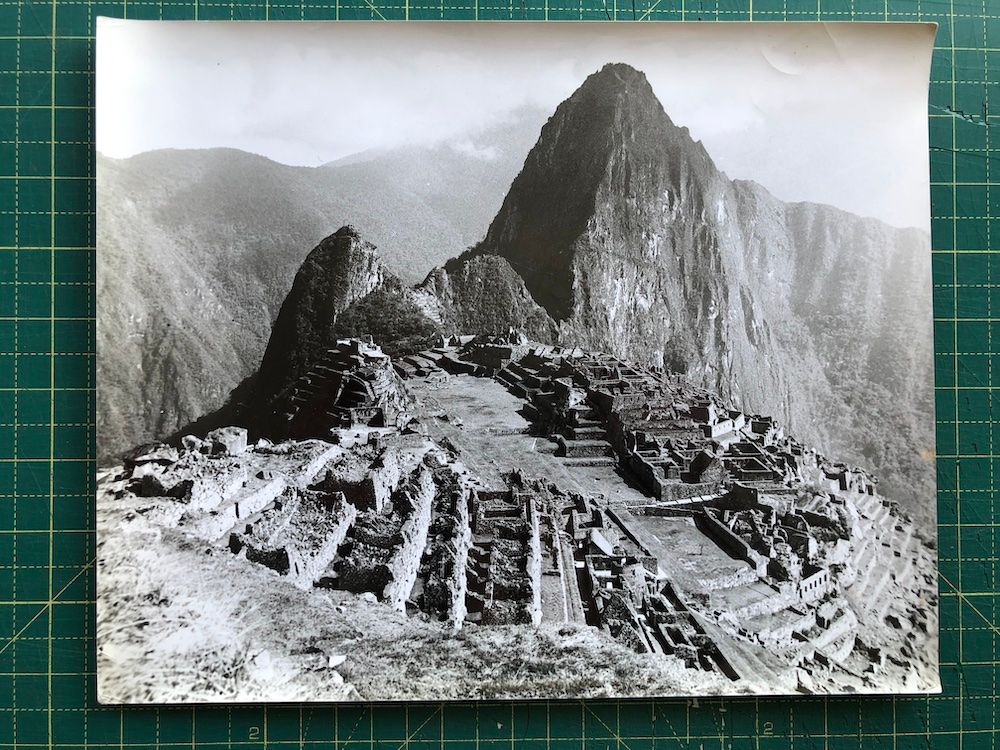

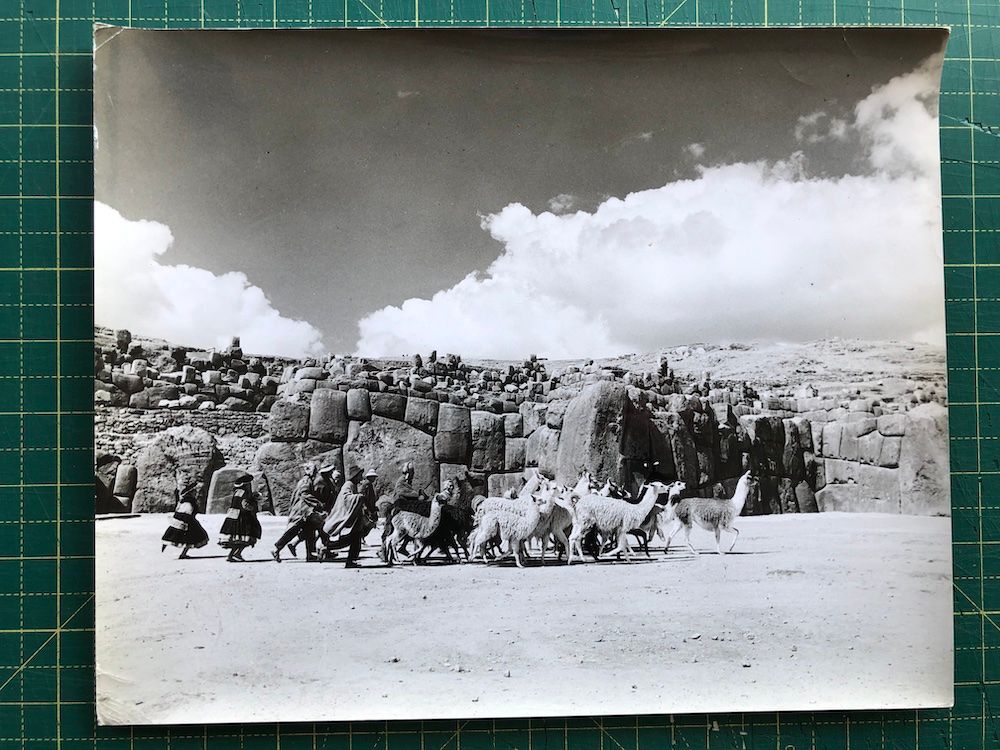

“There’s a lot of fascinating correlations between different ancient cultures. Mayans [sic] and Egyptians were on opposite locations on the planet, but both had similar production techniques. Some of the gods and deities, on paintings and carvings on the walls, were similar.”

The Moai (as the carved stone heads are more properly known) of Rapa Nui didn’t wind up inducted into the lore of Stargate SG-1 and the Maya pyramids featured only once – ‘Crystal Skull’ (S3, Ep21) – but it’s noteworthy that these two ancient alien favorites loomed so large over the production in its first year.

Stargate and the 1990s Ancient Alien Renaissance

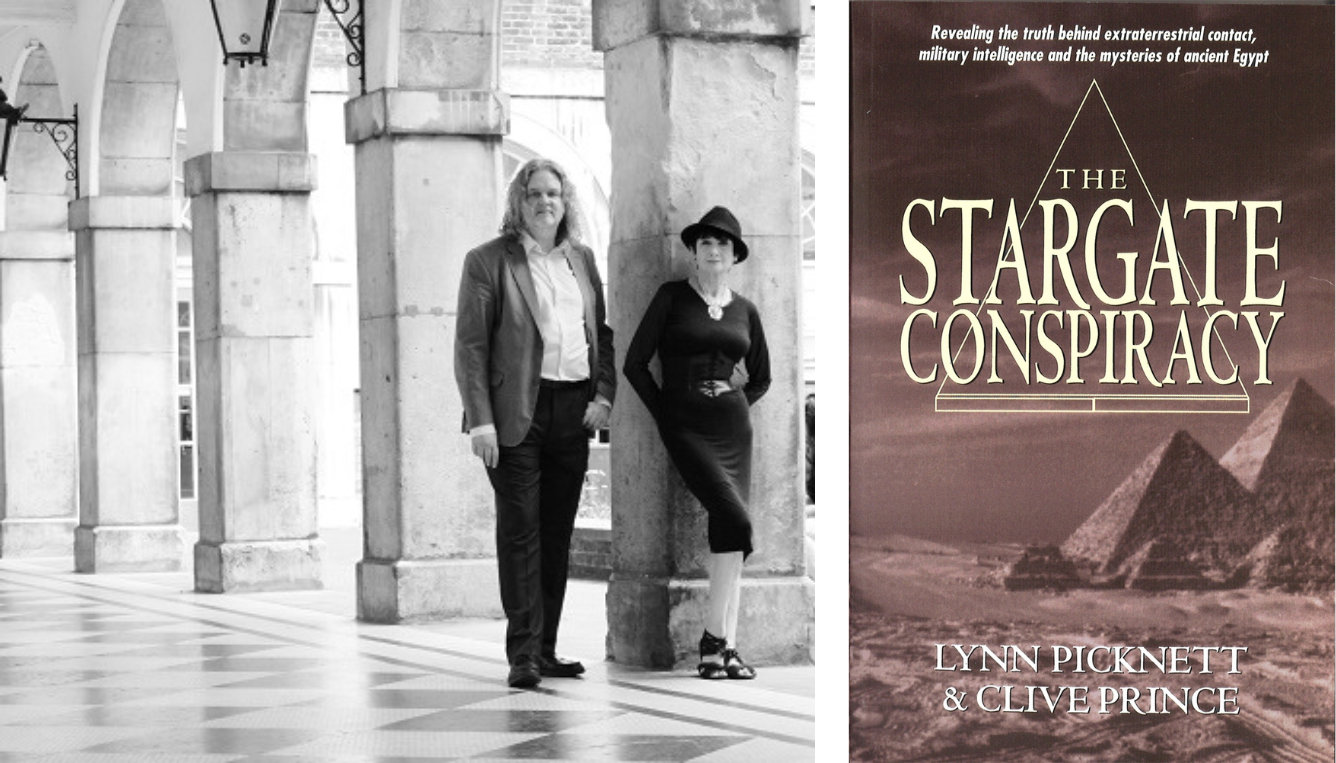

Certainly, Roland Emmerich has talked about being influenced by the big dogs of ancient alienism like Erich von Däniken, Zecharia Sitchin, and Philip Coppens, while if one reads deeper into the subculture, it’s clear that the Stargate concept evolved alongside the work of some of the smaller fish in the space, like Dale E. Graff, Clive Prince, and Lynn Picknett.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, there was a resurgence in this kind of literature, generally revolving around the year 2000 and some of the apocalyptic notions associated with it.

Prince is the co-author with Picknett of 1999’s The Stargate Conspiracy. “At the time we wrote [the book], it was all leading up to the millennium and there was a lot of stuff in books about Ancient Egypt, who built the pyramids,” he says.

“As we’re looking at this new wave of books, all these things were converging on the same answer which was the gods of Ancient Egypt built the face on Mars and therefore was extra-terrestrial. It was all linking into this belief system which has been around since the 1950s, about this group of people who believed they were in psychic contact with the very same extra-terrestrials.”

Some of you might recognize this as sounding very like the tenets of Theosophy, a movement that inspired H.P. Lovecraft and which was founded by Helena Blavatsky in the late 19th century. Wikipedia describes its key tenet as being “[an] ancient brotherhood of the spiritual adepts known as the Masters…[who] are attempting to revive the knowledge of an ancient religion once found around the world and which will come again to eclipse the existing world religions.”

And really, that’s where all this starts. An M.O. that would go on to be visible in everything from L. Ron Hubbard’s Scientology to the creation of the Raëlian cult by Claude Vorhilon which argues humans were genetically engineered by aliens 25,000-odd years ago.

Roland Emmerich, Erich von Däniken, and Zecharia Sitchin

Yet while this theory may sound outlandish, it actually does have some basis in science (bear with me here). Yes, we’re subject to the Fermi Paradox, which battles with the conflict that we’re seemingly yet to have first contact with aliens (outside forests in rural America) even though a technologically advanced species should have made their way here by now.

But no less a molecular biologist than Francis Crick pondered the theory of panspermia (‘directed panspermia’ in Crick’s case), a hypothesis proposed by Swede Svante Arrhenius in 1907 and deliberated by iconic physicist Carl Sagan in his book with co-author I.S. Shklowskii, Intelligent Life in the Universe (1966).

“Arrhenius suggested that terrestrial life did not originate on Earth. He imagined that simple living forms may have drifted from world to world, propelled by radiation pressure through interstellar space,” the duo writes.

“What objection, in principle, could there be to spores making this magnificent cosmic journey from planet to planet and from star system to star system and then, by chance, falling on a planet where conditions were suitable, reviving and initiating life?”

Crick’s addition of this panspermia being directed – that is not just space moss stuck to a rogue asteroid – chimes with the idea of ancient astronauts.

Shklowskii and Sagan mention Thomas Gold, who essentially said humans might be descended from the remnants of an alien picnic on Earth, while otherwise suggesting a theory we see in many of our own sci-fi films, “to distribute the genetic material of the home planet so that in case of a disaster, the evolutionary patrimony is not irretrievably lost.”

In other words, so that alienkind, so to speak, can continue in the same way we aspire to for humankind (who would in this scenario also be essentially aliens if you think about it).

Scoot forward a few decades and you end up with Roland Emmerich watching the documentary based on Erich von Däniken’s seminal book Chariots of the Gods? (1968), while Zecharia Sitchin is writing his texts about the Anunnaki – a race of alien astronauts led by one called Enki who arrived on Earth almost half-a-million years ago and set up shop by a delta “formed by the twinlike Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers as they flow into the Gulf.”

Sitchin believed the Anunnaki came here from the planet Nibiru to mine gold and their existence can be proved by correctly reading the Book of Genesis. In fact, he said we have alien DNA available to test right under our noses, thanks to our recovery of various old Sumerian artifacts. The remains of the Sumerian monarchs Puabi, also known as Queen Shubad, and King Meskalamdug (who is sadly for him only a demigod) reside somewhere in the British Museum archives like at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), where, despite Sitchin’s pleading, they remain undisturbed.

“It is my fervent hope,” he writes in There Were Giants Upon the Earth (2010), “that by showing that the remains of Puabi are no ‘routine’ matter, this book will convince the museum to do the unusual and conduct the tests.”

Of course, where these kinds of authors come together is in the way they rail against the so-called status quo – a consensus within archaelogy that tries to shut down Sitchin’s ‘discoveries’ and adhere to the mainstream.

Daniel Jackson and Archaeology’s “New Orthodoxy”

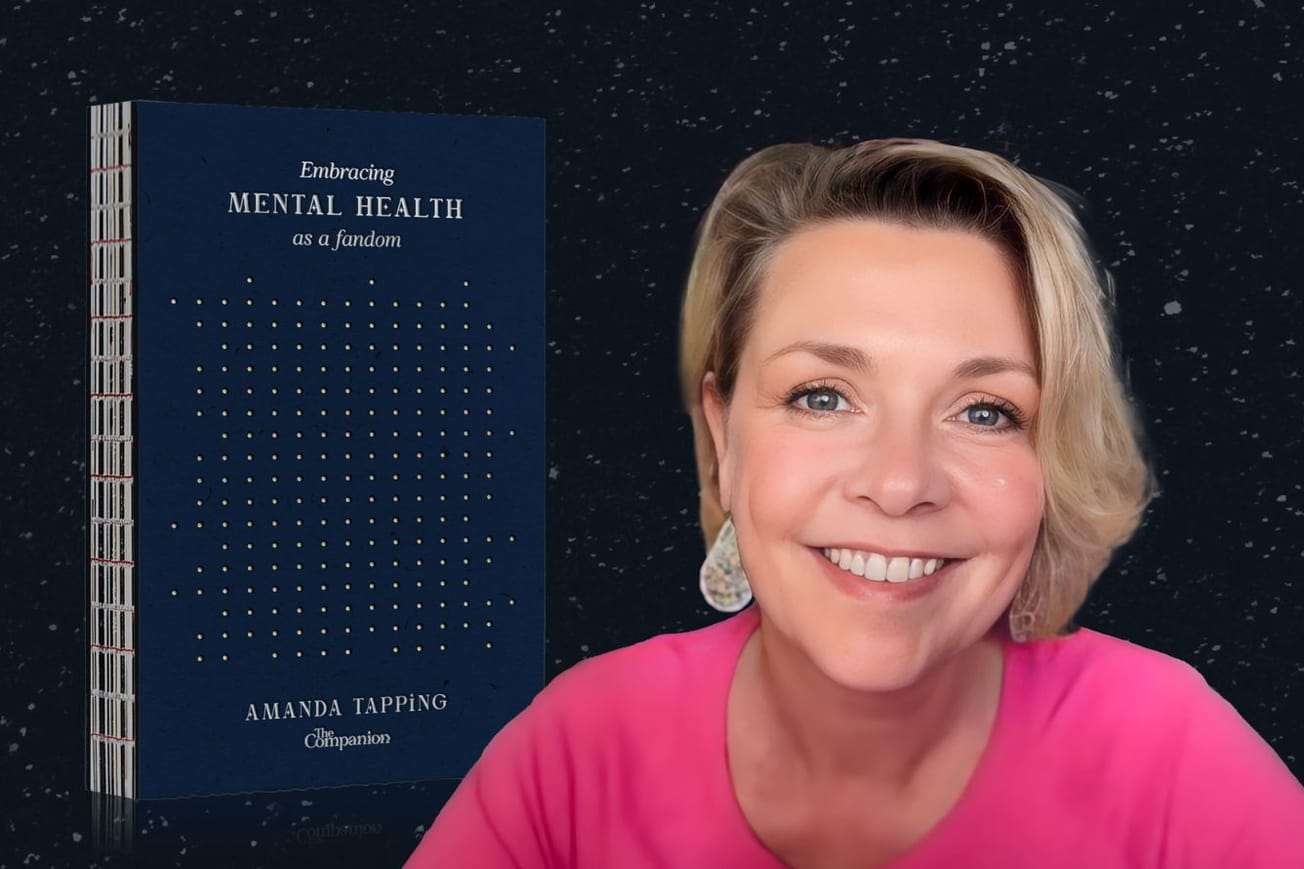

And it’s why Stargate’s Daniel Jackson in some way legitimizes these eccentric fringes. He’s both a ‘proper’ scientist, but also someone who appears to be open to what Picknett and Prince called “exponents of the New Orthodoxy.”

Philip Coppens’ book The Ancient Alien Question (2011) calls on its readers to “question everything. Especially authority,” echoing Donald Trump’s attack line of alternative facts or British MP Michael Gove’s defiance of experts.

However, in his review of the book in the journal American Antiquity, Jeb Card also writes, “Mainstream academic research is presented if it seems ‘mysterious’ or ‘anomalous’. A discussion of recent research on pre-Columbian geoengineering of the Amazon basin and highly-productive ‘slash-and-char’ terra preta is not extra-terrestrial, but Coppens includes it because it sounds like the science fiction concept of terraforming…”

“I’ve made my peace with it,” says Dr. Krueger, of the attacks by von Däniken and his ilk. “You can get mad about these things and you can spend endless books debunking [them], but there’s no point.”

Indeed, Benjamin Kelly from Canada’s York University claims in his article Deviant Ancient Histories: Dan Brown, Erich von Däniken and the Sociology of Historical Polemic, that there is even a “distinct sub-genre of ancient history writing: polemics, aimed at a general audience, which attack fringe works for ancient history.” Kelly posits there were at least six of these kinds of books vigorously criticizing von Däniken before the end of the 1970s.