One of the most memorable sequences in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) was the Death Star trench run. A squadron of small rebel fighters use their speed and maneuverability to face off against the Death Star, the remorseless face of the Empire and ultimately destroy the moon-sized battle station with a one-in-a-million shot.

It’s an unmatched climax by any criteria, as Han Solo finds his heart and Luke Skywalker digs deep to find the core of Obi-Wan’s teachings – all set against a thrilling dogfight with Darth Vader. We spoke to Denis Lawson (Wedge Antilles) and Garrick Hagon (Biggs Darklighter), as well as concept artist Colin Cantwell (via his partner Sierra Dall), and (courtesy of Ed Kramer) animators John Wash and Jay Teitzell about how they created the definitive sci-fi space battle.

As Told By

- Colin Cantwell (additional spacecraft design: miniature and optical effects unit)

- John Wash (computer animation and graphic displays: miniature and optical effects unit)

- Jay Teitzell (computer animation and graphic displays: miniature and optical effects unit)

- Denis Lawson (actor, Wedge Antilles)

- Garrick Hagon (actor, Biggs Darklighter)

Influences on the Death Star Trench Run

The Death Star trench run was a ground-breaking moment, both for Star Wars and the film industry: nothing like that had been filmed before. Although there were no cinematic precursors to this moment, there are distinct similarities with military war footage. The shot of the X-Wings and Y-wings as they fly toward the Death Star evokes the classic images of Spitfires and Hurricanes flying toward the climactic Battle of Britain in 1940.

Another cultural touchstone was Operation Chastise; the allies’ attack on German dams in 1943 by Royal Air Force Squadron No. 617, using purpose-built bouncing bombs to hamper the German war effort. The Möhne and Edersee dams were breached, but the Sorpe Dam sustained only minor damage. Two hydroelectric power stations were destroyed and several more were damaged. Although the RAF lost 56 crew, including three captured, the mission was deemed a success.

Operation Chastise was later immortalized on screen in the 1955 black-and-white film The Dam Busters. Although Operation Chastise also later inspired the 1964 full-color film 633 Squadron, The Dam Busters was a key source of inspiration. Footage from the movie was even used in the executive and test screenings of Star Wars: A New Hope, according to Steven Spielberg who was there. This is not as surprising as it might seem, as cinematographer Gilbert Taylor worked on both.

Enter Cinematographer Gilbert Taylor

Taylor – who passed away in 2013 at the grand age of 99 – spent World War II filming night-time bombing raids over Germany with the RAF, as well as post-liberation footage at Nazi concentration camps. Following the war, he became a special effects photographer, working on The Dam Busters, Dr. Strangelove (1964), and The Omen (1976), before applying his talents to Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope.

Unfortunately, throughout the filming of Star Wars, the director George Lucas was an elusive person to discuss ideas with, according to Taylor. This led to Taylor making his own decisions about how best to shoot the picture, after multiple readings of the script. However, this resulted in differences of opinion between the director and cinematographer, which ultimately led to the studio 20th Century Fox intervening to retain Taylor in the production.

After his experience working on Star Wars, Taylor decided he would never work with Lucas again. Nonetheless, Gilbert’s legacy endures, as he established the visual aesthetics for Star Wars in A New Hope, which have been indelibly maintained throughout the subsequent films in the series.

Creating the Ships and the Death Star

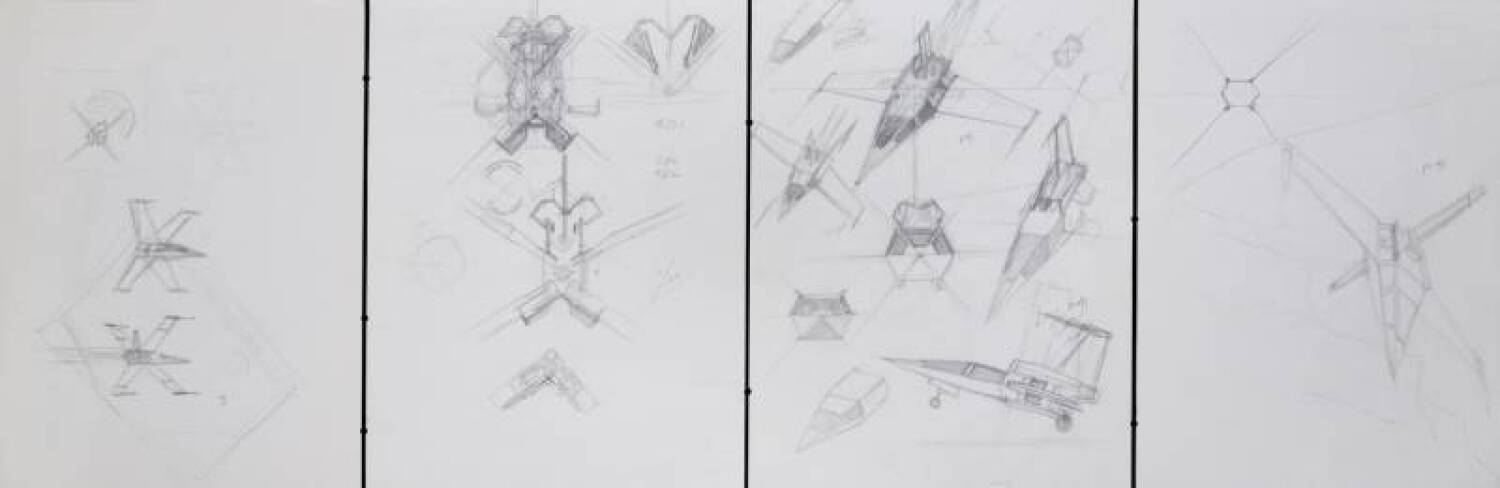

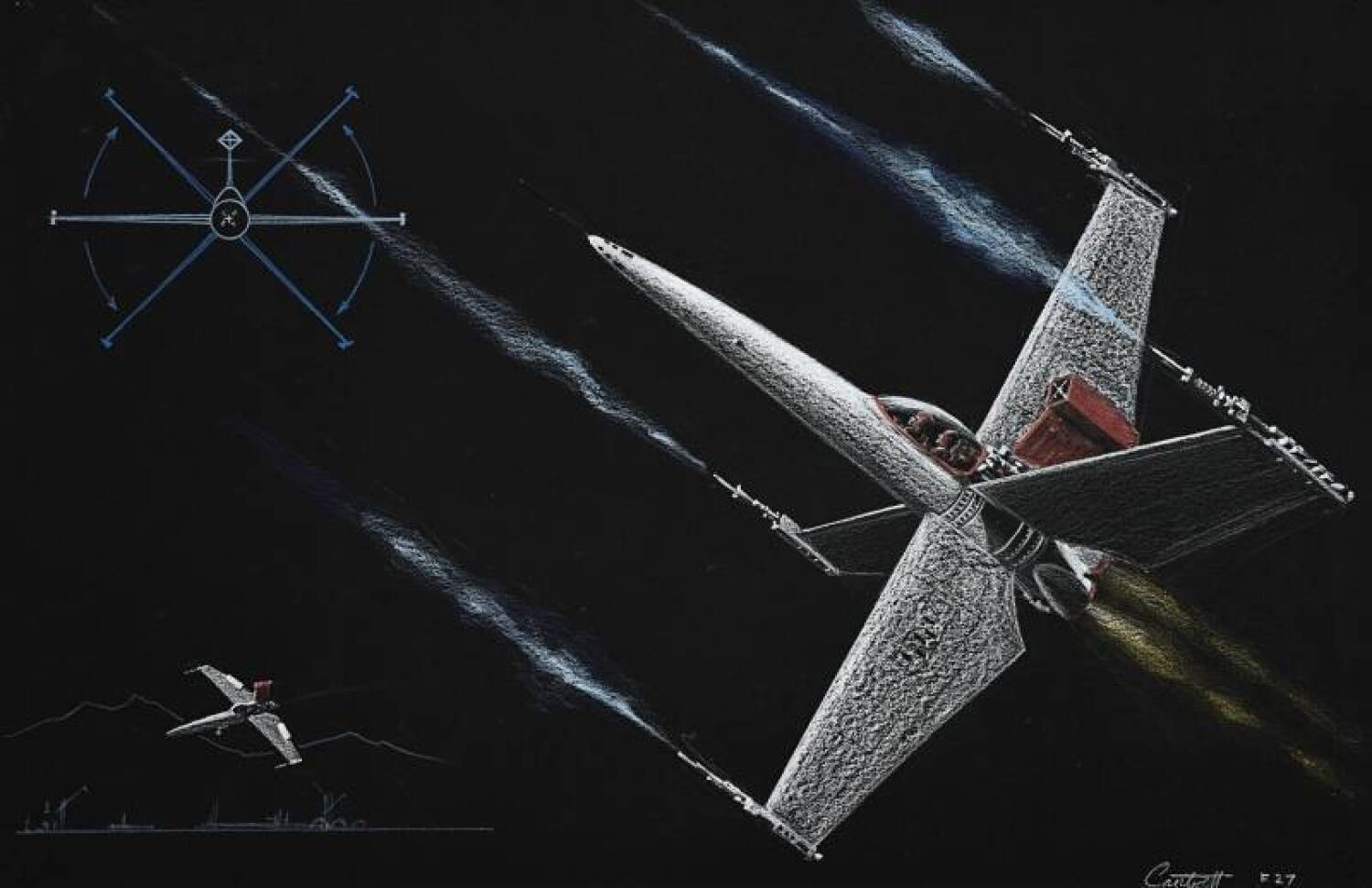

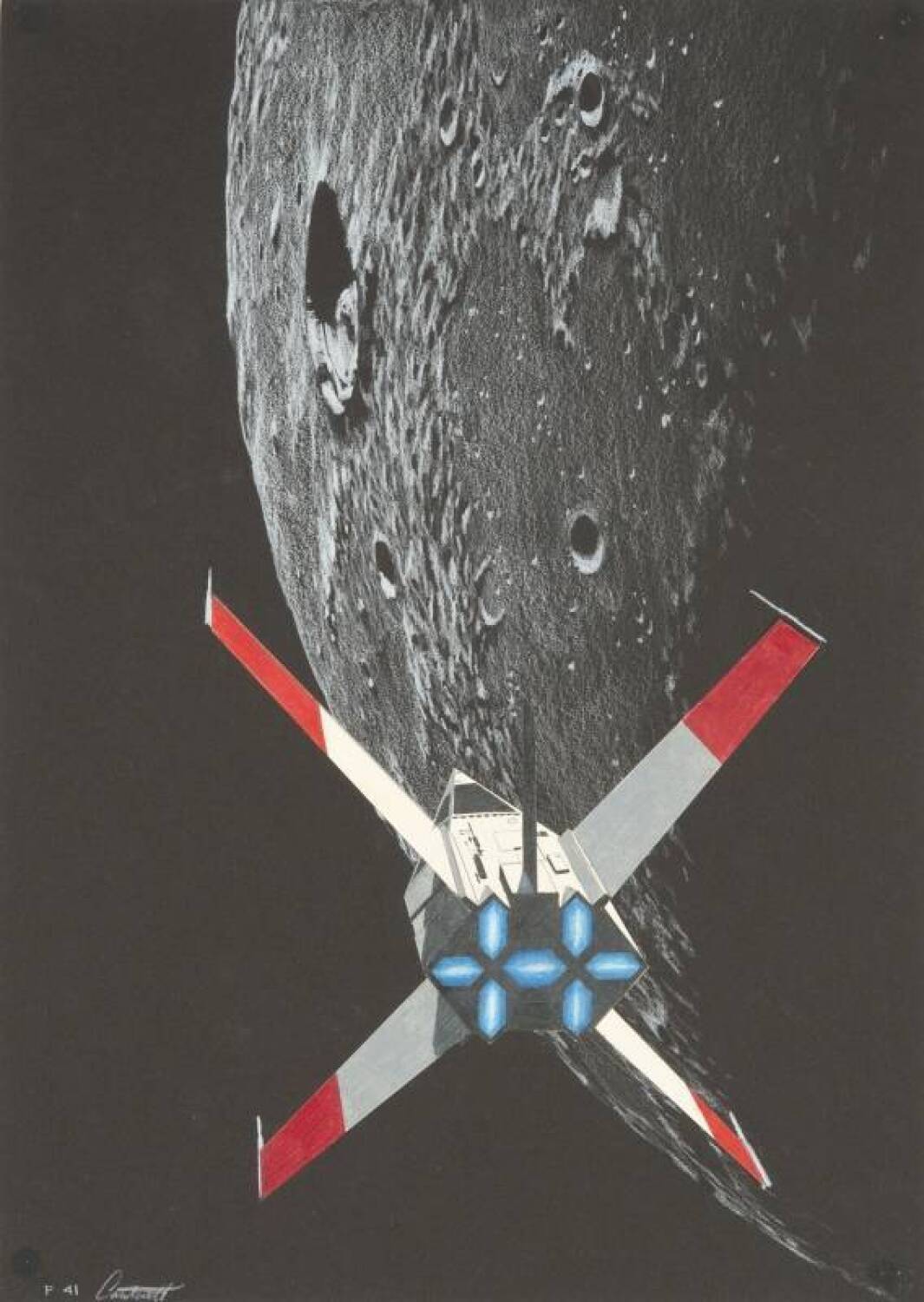

But who would design the iconic spaceships that became the cultural touchstones of a generation? Even before the film was in production, Lucas turned to concept artist Colin Cantwell, to visualize his screenplay. Cantwell began creating spaceship concept designs while Lucas was still looking for a studio. The concepts were drawn with pencil on dark paper, better mimicking the environment they would operate in.

Concept art and pre-production sketches by Colin Cantwell for what would become the iconic X-Wing starfighter in Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. | From JuliensLive.com.

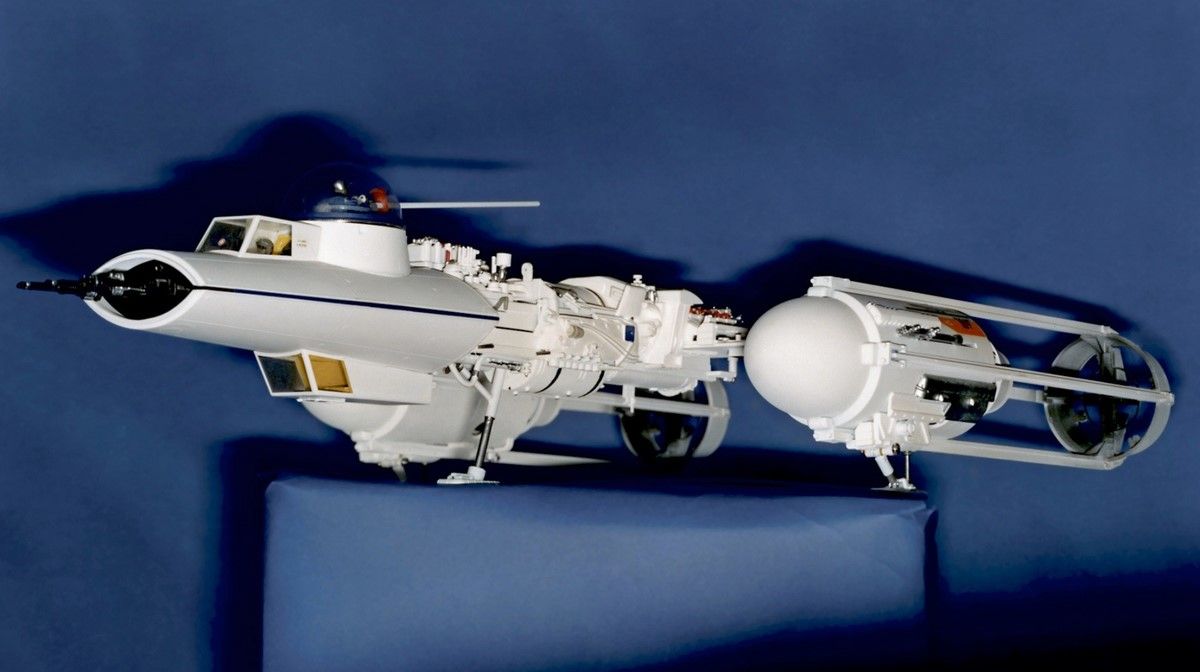

Once the concept designs were agreed upon and finished, Colin sketched schematics of the various ships in more detail, before creating a prototype from which the special effects teams could create their models. “I do not believe that his actual models were used in the movie,” says Sierra Dall, on behalf of her husband. “Except Luke was playing with Colin’s model of the Skyhopper in the first few scenes of A New Hope.” He had a hand in the earliest designs for the X-Wing, Y-Wing, TIE fighter, Star Destroyer, and Millenium Falcon – the latter repurposed as the Rebel Blockade Runner whose attempted escape opens the movie.

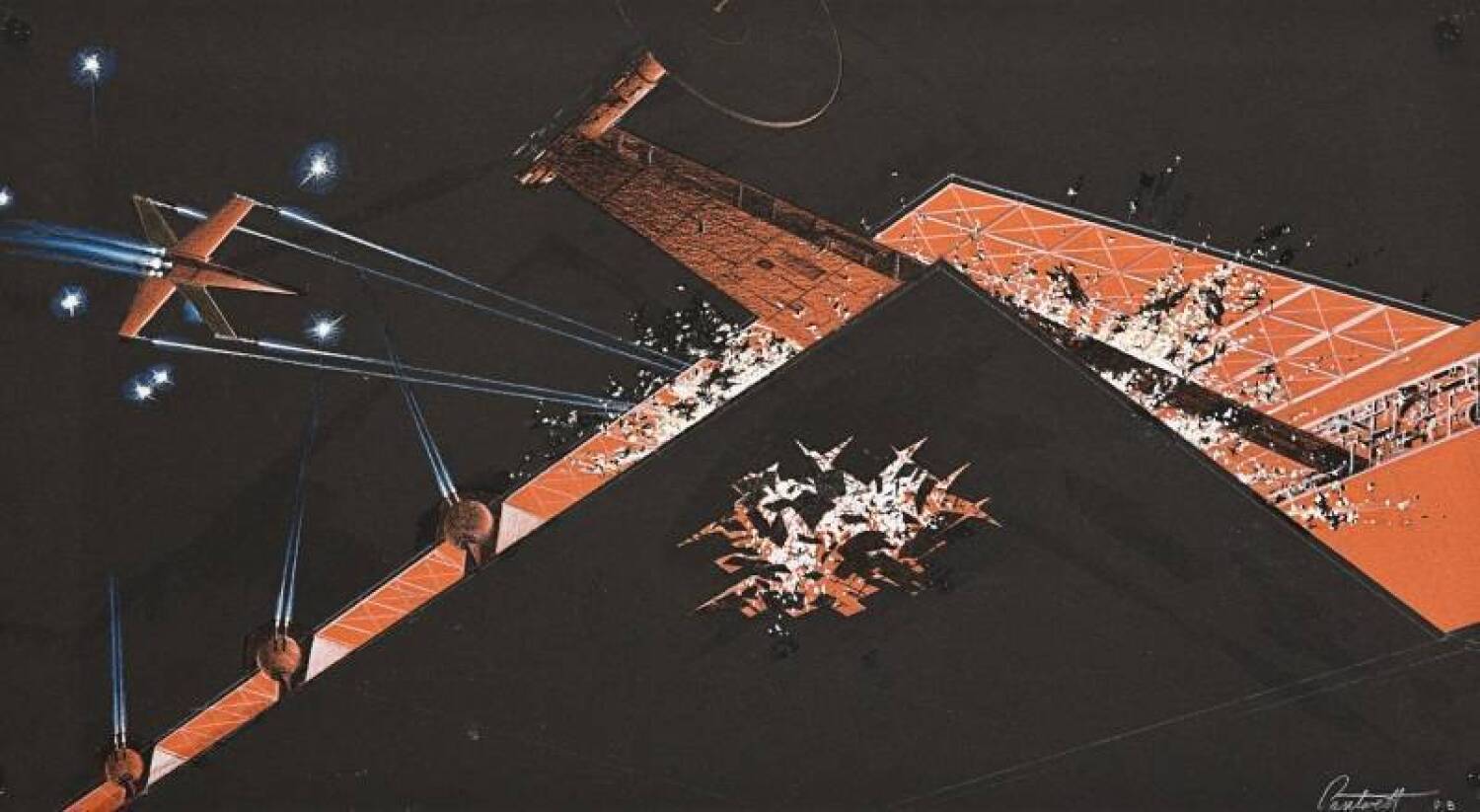

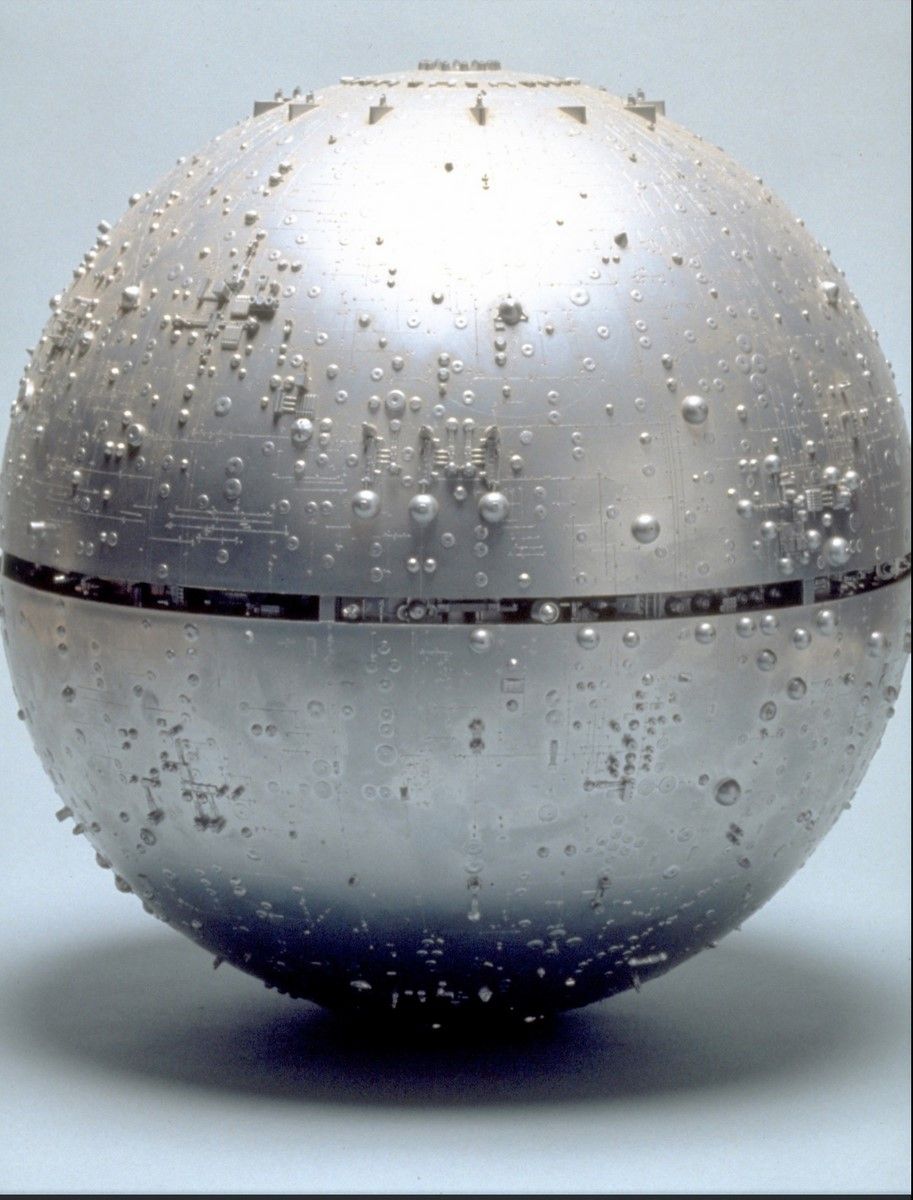

Cantwell originally envisioned the Death Star as a perfect sphere. To create the Death Star model, Cantwell ordered a styrene globe. Unfortunately, when the globe arrived, it was in two halves. After scribing each half in detail, Colin began fitting the two halves together and discovered that the edges of the equator had shrunk.

This became a source of concern, as a shrunken equator meant that the Death Star would no longer be the sphere that he originally proposed. Smoothing the connection between the two halves, to the point where it would no longer be visible, was nearly impossible. Discussion the issue with Lucas during a telephone call, Cantwell suggested having a trench around the equator of the Death Star. As well as solving this problem, it would also provide the Rebel spaceships with something to dive in and out of, while being shot at from either side of the trench.

A selection of Colin Cantwell’s original kitbash models for the TIE Fighter, Death Star, X-Wing, and Y-Wing. These designs, which were later refined by the ILM model shop, would all play a vital role in the climax of Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. | OriginalProp.com.

To jump forward by several decades, during the production of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), it became clear to the team at VFX house Industrial Light and Magic that the Death Star trench attacked by the Rebel Alliance is not in fact the equatorial trench, but a different trench running north-south. ILM lead artist Todd Vaziri wrote about the process on his blog, FXRant, undoing generations of misunderstanding about the changing geography of the Death Star.

Also influential were Cantwell’s illustrations of the X-Wing – its characteristic S-foils inspired by the Old West gunslinger drawing his irons – and the TIE fighter, both of which made it to the screen largely unchanged. A prolific ‘kit-basher’, Cantwell created prototypes of the dueling starfighters (“The early versions were very close to Colin’s original designs,” confirms Sierra), and ILM’s model shop was tasked with crafting their cinematic counterparts.

The Death Star itself – and its subsequent explosion – was a task for John Stears. Stears had been making a name for himself with the James Bond films. He had designed James Bond’s Aston Martin DB-5 for Goldfinger (1964), as well as the avalanche in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). However, by the mid-1970s, following The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), Stears had become disenfranchised by the James Bond films.

Thus, in 1976, Stears received a telephone call from Lucas, who was a fan of the James Bond films and wanted to know if Stears was interested in creating mechanical and electrical effects. As well as creating the Death Star, Stears was also credited, along with the special effects artist John Dykstra, for the film’s climactic dogfight.

Dykstra was hand-picked to lead the newborn ILM team – his fractious relationship with Lucas saw him removed from the production, but not before developing techniques that would net Star Wars Academy Awards for best special effects and special technical achievement. The computer-controlled ‘Dykstraflex’ system effectively allowed the dynamic model shots against a blue screen to be matched to a carefully programmed background shot, creating groundbreaking compositions that echoed the energy of aerial combat in a way that had never been previously possible.

Further Listening: How Mark Seigel Made It at ILM

CGI Fridays | How ‘Monster Kid’ Mark Siegel Made it at ILM - From clown college to CGI, Mark Siegel talks Ghostbusters, Star Wars, ET, and getting into the industry in Ed Kramer’s CGI Fridays podcast.

For example, in the scene above, the X-Wings were shot first, and then in a separate shot, the camera moved along the Death Star trench in a different direction and at a different speed. With Dykstraflex keeping the movements and angle consistent, the two negatives could be printed together to create a single sequence that puts you right at the heart of a daring dogfight.

Creating the Targeting Computer Graphics

Whilst ILM used the latest innovations to render realistic space combat, the team responsible for the X-Wing and TIE Fighter targeting computers relied on more established animation methods. Whilst the bulk of the Rebel briefing used some of the very earliest computer-generated graphics by Larry Cuba, the in-universe graphics for the Battle of Yavin itself were created frame by frame by John Wash, Jay Teitzell, and Dan O’Bannon using an Oxberry camera mounted above a pane of glass – a technique already a decade old.

“When George was doing prep on the movie, we were all working for a company called Universal Commercial Industrial Films,” explained John Wash to The Companion‘s VFXpert Ed Kramer. “Jay and I worked mainly as editors and animators there – George asked about animators and my name got in front of him.”

Watch More: Ed Kramer's CGI Secrets Full Video

Ed Kramer’s CGI Secrets Full Video - In Ed Kramer’s CGI Secrets, you’ll hear incredible stories from the making of some of the biggest sci-fi movies of the 1990s and 2000s

“I went down for this really interesting interview. He was at this little office on Seward Street in Hollywood, I talked to him for maybe half an hour about what he wanted to do and this all involved mainly the trench and the graphic journey down the trench.

“We weren’t going to use any kind of computer technology at all, because most computers at that time were in research facilities and really weren’t open [for] use by the entertainment business or the general public. Both Jay and I had done a lot of mimicking computer animation using downshooters, using animation cameras, backlit gels…”

Backlit gels traditionally create more vibrant colors than front-lit animation, perfect for the luminous tone of Rebel and Imperial computer displays. By moving different transparencies with different gel images on, Teitzell tells us, “built through multiple passes of the Oxberry downshooter, you could get the effect of different color layers moving in an independent way that really mimicked three-dimensional control.

“We had no choice [but to animate it in this way], we knew we had to mimic graphics being displayed by machines of either the Empire or Rebellion. The idea was computer graphics even before… I’m not even sure the term existed.”

Shooting the Pilots of Red Squadron

The special effects team was in place, but people were needed to pilot the X-Wings and Y-Wings. Without them, it would just be models shooting at each other. These pilots would become the face of the Rebel Alliance, facing off against the might of the Empire; where every ship lost would be a pilot who did not survive.

The script for the space battle was 20 pages long and was filmed in London during the summer of 1976. With temperatures peaking at over 35°C, the previously green fields of England were now brown, as the country sweltered in a heat wave, leading to drought conditions. However, those who had been filming the Tatooine scenes in Tunisia had become acclimatized to the heat.

The heat wave and filming process meant many of the actors who played the pilots were often sitting together outside the sound stage between takes. “A lot of us knew each other, particularly the British actors, as we were all in our twenties,” recalls Denis Lawson (Wedge Antilles, aka Red Two), in conversation with The Companion at Wales Comic Con. “The summer of ‘76 was very hot. We would sit outside chatting away, so we naturally bonded. It was through that Mark [Hamill] became a good friend of mine.”

This bond between the actors ensured the dialogue between the pilots felt natural. There was an easy familiarity between them, which came across in the film. This was despite the filming process, which required each actor to say their lines independently of each other.

A wooden platform had been created, mimicking the cockpit, with a screen behind the pilot, upon which the digital effects would be added in post-production. “The floor crew around the platform provided the movement of the aircraft by shaking it – that’s how simple it was,” explains Garrick Hagon (Biggs Darklighter, aka Red Three) to The Companion.

“In front of me was an early type of computer game, in which George [Lucas] advised me to poke at random.”

This deceptively simple filming technique allowed Lucas to focus on the pilots in their cockpits, whilst the Battle of Yavin raged on around them. The early computer game console gave something for the pilots to interact with, further reinforcing the illusion that they were flying a spacecraft in the middle of a battle.

The motion of the spacecraft was created through a similarly simple technique. Over the heads of the pilots was a wire gantry, upon which a light was attached. This light would slowly move across, giving the impression that the spacecraft was moving in relation to the nearby star. “It was that rudimentary,” says Hagon. “A moving light [was] done by mechanical means and platform shaking done by human hands.”

As only one platform had been built, each pilot had to record their lines independently of each other. “George [Lucas] thought you could just say your lines with no cues, one after the other,” recalls Lawson.

“George was extraordinary, but he was not experienced with actors. You had to explain to George that it doesn’t work that way. What we decided to do was that George would sit behind a camera with the script and shout a line at me, and I would say a line back.”

Saying their lines in response to Lucas’s cues allowed the actors to evoke emotion in their conversation during the battle, giving the scene a “very immediate feel”, as Lawson describes it. Lucas would record several takes of each line encouraging the actors to “Do it faster and with more energy.”

The footage was then sent to ILM, and it was there that the effects were added, bringing to life one of the greatest space battles in cinematic history. “There were directions in the script, but we didn’t really know what was going to happen behind us, because all that stuff was so new,” says Lawson. “The first time I ever heard about a computerized camera, and I wondered ‘What the hell is that?’ That was the first hint of something different.”

Reflecting on the Death Star Trench Run

The first time they saw the finished results was at the cast and crew screening in Leicester Square, London. “That first shot, where the ship came over the top of the camera; it wasn’t just the visual, but the sound quality as well,” recalls Lawson. “I had never seen a shot like that in my life, it was quite remarkable. You really felt ‘This is different’.”

The success of Star Wars: A New Hope paved the way for the future of the Star Wars franchise. Whilst Biggs Darklighter did not survive that fateful assault on the Death Star (nor did his back story with Luke escape the cutting room), Wedge Antilles saw combat again in Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back and Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi. Through this, Lawson, as Wedge, became the face of the X-Wing pilots, inspiring a generation of future pilots.

“A couple of guys have said to me ‘I became a pilot because of you’. I didn’t fly, I just sat in a chair. It’s extraordinary and very unexpected.”

Lawson most recently pulled on the orange flight suit for a cameo in Star Wars: Rise of Skywalker (2019). “JJ Abrams emailed me directly and I rang my agent to ask if someone was taking the piss,” remembers Lawson with a laugh.

Originally it had been envisioned as a more significant role, recorded over five days, with Wedge Antilles being part of the scenes after the final battle. Unfortunately, scheduling meant that Lawson could only commit to one day, leaving us with a single shot of Wedge in the gunner seat of the Millennium Falcon as Lando’s fleet advances towards the First Order star destroyers.

It is unsurprising that the final film in the sequel Star Wars trilogy should end on a climactic space battle, with the fate of the galaxy at stake. The Death Star Trench Run was a ground-breaking moment in cinema, brought about through innovative filmmaking and amazing performances.

“We were just lucky to be in one of the greatest space battles in film,” concludes Hagon with a smile.

This article was originally published on January 20th, 2022, on the original Companion website. Colin Cantwell passed away shortly afterward on May 21, 2022, at the age of 90.

Further Reading on All Topics

- CGI Fridays | How ‘Monster Kid’ Mark Siegel Made it at ILM - From clown college to CGI, Mark Siegel talks Ghostbusters, Star Wars, ET, and getting into the industry in Ed Kramer’s CGI Fridays podcast.

- Ed Kramer’s CGI Secrets Full Video - In Ed Kramer’s CGI Secrets, you’ll hear incredible stories from the making of some of the biggest sci-fi movies of the 1990s and 2000s

- “I Looked Shit-Hot”: An Oral History of Imperial Officers - From A New Hope's Grand Moff Tarkin to Andor's Deedra Meero, Imperial officers are the very human face of tyranny in the Star Wars saga.