Imagine you and I are Starfleet officers on shore leave. Rather than jet off to Risa (the ‘pleasure planet’) for the 20th time in a row, we make a quick 40-light-year trip to the planet Trill instead.

When we arrive, we bypass the popular Hoobishan Baths and head down into the depths of the planet to find the Caves of Mak’ala, a series of tunnels filled with glowing, interconnected pools of milky water.

We watch as worm-like creatures a little smaller than our forearms swim around the pools. It’s not long before a robed Guardian approaches, who (begrudgingly, we’re hanging out in a very sacred space, after all) explains these are Trill symbionts. He tells us that they can stay here in the pools or, if they want to get out, they can be ‘implanted’ into a Trill humanoid host.

A network of caves and worm-like creatures that need a human host. It sounds more body horror than a holiday, right? That’s no surprise. Sci-fi has taught us that symbiotic relationships don’t end well for the host.

Think of the Facehuggers in Alien (1979). They latch onto a host’s face, use their chest to incubate a baby Xenomorph, and leave them very dead when they burst out. The parasites from The Faculty (1998) burrow into a host’s brain through their ear and then take over their bodies. And there’s the ‘thing’ from The Thing (1982), a parasitic alien that infects and assimilates its hosts before imitating them.

A similar bug-like being also nearly led to the downfall of Starfleet and the murder of Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) in Star Trek: The Next Generation (‘Conspiracy’ – S1, Ep25) when an army of pink parasites took residence at the top of their hosts’ spines.

But don’t worry, that’s not how things work here on Trill. When we meet the ‘joined’ Trill Jadzia Dax (Terry Farrell), one of the main characters in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, we learn that it’s a great honor for Trill humanoids to become hosts. They work hard, train hard, collect degrees like you collect Pokémon, and compete with others for the privilege of becoming a host. Even if we wanted a Trill symbiont implanted into our stomachs at this point, we wouldn’t stand a chance.

The Trill’s style of symbiont-host relationship certainly isn’t as typical in sci-fi as the chest-bursting, brain-controlling variety. However, science shows us many different types in the real world—some much closer to home than you might realize.

Symbiosis Explained

“Symbiosis was originally a term coined by Anton de Bary [a German botanist, microbiologist, and mycologist] to mean two organisms, differently named, living together,” says Irene Garcia Newton, an Associate Professor in the Department of Biology at Indiana University Bloomington who specializes in microbial symbiosis. “It is a very broad definition meant to encompass negative and positive interactions, as long as they are long term associations.”

Newton says the key thing you need to know about symbiosis is: it’s everywhere. “Pretty much all animals and plants have microbial symbionts—sometimes bacteria, sometimes fungi, sometimes both,” she explains. “Everything has a symbiosis, even you.”

However, as we’ve learned from several of the sci-fi examples earlier, symbiosis can look drastically different on a case-by-case basis. This is why there are three types: commensalism, mutualism, and parasitism.

Commensalism; or, Don’t Mind Me

Commensalism is a type of symbiotic relationship where one living organism benefits and the other doesn’t benefit or suffer. They simply don’t get anything out of the deal.

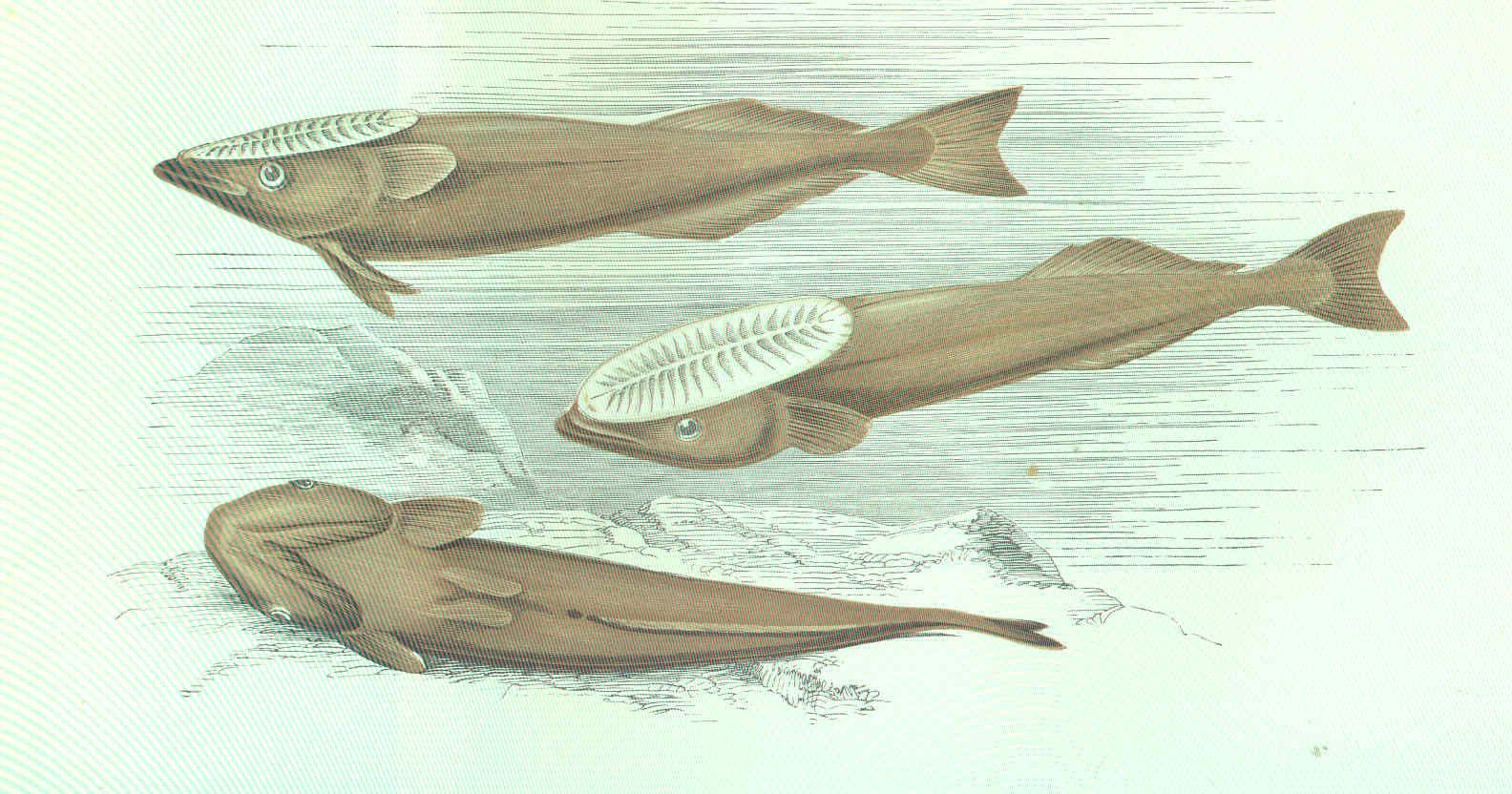

There are many real-world examples of commensalism. Jackals separated from a pack have been spotted following tigers around and eating their leftovers. Hermit crabs use the shells of dead creatures to upgrade their homes. The remora fish is one of my favorites, which hitches a ride on the side of giant sea creatures for transport, protection, and to eat the bigger animal’s leftovers.

Out of the three, this is the type of symbiosis with the fewest examples in science fiction. I think that could be because there’s not much drama compared to mutualism and parasitism, which we’re about to encounter next.

However, in Star Trek: The Original Series (‘Wolf in the Fold’ – S2, Ep14), we do hear of (but, unfortunately, don’t meet) a species called the Drella that feed on love, which could be commensalism, but we never get to find out for sure.

Star Wars fans might also argue that the midichlorians, which Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) calls “a microscopic life form that resides within all living cells,” are an example of commensalism. It’s these life forms that channel the Force, allowing those sensitive to it to tap into its power. Then again, we don’t know enough about the fictional science of the midichlorians, and this could be mutualism instead.

Mutualism; or, Everybody Wins

Mutualism is a symbiotic relationship in which both living organisms benefit. We see this type of symbiosis loads in the real world. For starters, more than 80 percent of plant and tree species depend on mycorrhizal relationships with fungi. They give the fungi sugars, and the fungi provide them with water and other kinds of nutrients.

Many birds have this relationship with larger animals, like the oxpecker, which picks parasites off big mammals, like rhinos—a good meal for the oxpecker and better health for the rhino.

Anemones and clownfish (or anemonefish) have a similar close bond. Anemones have stinging tentacles that subdue prey, like crabs and fish. But clownfish are immune, so they hide from predators among the anemone, a win for the clownfish. But they also keep the anemones free from parasites, and provide them with nutrients from their feces, and their bright colors might even lure in prey, a win for the anemones, too.

There’s also mutualism inside your body. Your gut microbiota helps you digest food, and it gets a place to live and things to eat in return. It’s a similar story for the microbes that live on your skin, which help promote immunity and prevent infection.

The Babel Fish in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1978) might be my favorite sci-fi reference. Pop one of these tiny yellow fish in your ear, and it’ll feed on the brain waves of everyone you encounter while also serving as a universal translator. It’s “possibly the oddest thing in the universe”, according to The Guide, but mighty handy, too. There’s also a Futurama episode called ‘Parasites Lost’ (S3, Ep2) in which Fry gets infected with worms that make him stronger and more intelligent.

Parasitism; or, Used and Abused

Parasitism is when one organism benefits and the other suffers. There are many instances in which you might play the role of the host. Think head lice, ticks, the tiny mites that cause scabies, and a whole bunch of tapeworms, roundworms, and other shaped worms that make you very ill.

Several examples of parasitism in nature sound so grim I’m a little hesitant to share them. Like the female hawk wasp, which stings and paralyzes a spider, lays her eggs in its body, and when the baby wasps hatch, they climb out, and their first meal is the spider—which is, horrifyingly, still alive throughout this whole process. If that hasn’t provided you with enough nightmare fuel, Google “zombie ant fungus”. But don’t say I didn’t warn you.

With these kinds of Cronenberg-esque scenes occurring in real life regularly, it’s no surprise sci-fi creators have dreamed up all manner of monstrous parasites of their own. We’ve already covered a few of these, like the parasitoid Alien Facehuggers that use a host’s body to grow a Chestburster, but there are plenty more.

In the very-The-Thing-like episode of The X-Files called ‘Ice’ (S1, Ep8), worms feast on a host’s brain and make them extremely violent. The Goa’uld species in Stargate SG-1 reside in a host’s neck and subsume their personality, transforming them into an absolute drama queen.

In Star Trek: The Original Series, there are several parasitic stories. The flying jellyfish-like parasites on the Deneva colony cause “a pattern of mass insanity” (‘Operation – Annihilate!’ – S1, Ep29). There’s also the Redjac, a noncorporeal parasite that possesses its host, turns it into a serial killer, and then feeds on fear—this is how Trek explains Jack the Ripper (‘Catspaw’ – S2, Ep7).

Symbiosis, Not So Simply

Although classifying symbiosis enables us to understand their differences and spot them the next time we watch a nature documentary or a sci-fi TV show—parasitic! mutual!—Newton warns this is a bit simplistic.

“The word ‘symbiosis’ in common usage has become synonymous with ‘mutualism’. This clouds our understanding of interactions,” she tells me. “The mechanisms and dynamics of mutualisms and parasitisms are very similar and also, mutualisms can break down and become parasitisms.”

We can see this in science fiction, too. For example, I’d class the artificially intelligent machines in The Matrix (1999) as having a parasitic relationship with humans. Humans scorched the sky in Operation Darkstorm, so the machines could no longer use the power of the sun. This wasn’t a problem for long, as the machines then used humans as an alternative power source instead. It certainly sounds parasitic, right? But maybe if you prefer the “juicy and delicious” steak in the Matrix compared to “the same goddamn goop every day” you get on the outside as Cypher (Joe Pantoliano) does, then it could be mutualism?

Let’s also consider the Goa’uld in Stargate SG-1, which might take over a host’s body, but give the host benefits, like an extended lifespan and boosted strength. Is that maybe a little bit of mutualism? The Tok’ra, a faction of the Goa’uld, also believes in the body’s equal sharing between symbiont and host, so not all are necessarily parasitic. (I’d still like them to stay as far away from my neck as possible, though, thanks).

What’s more, the Venom symbiote, which has a long history throughout Marvel canon, doesn’t fully take over its host’s body but often does force them to do pretty dangerous or violent things. Where does that sit on the scale between mutualism and parasitism?

Introducing the Trill in The Next Generation

If we had to categorize the Trill relationship, we’d be looking at mutualism. That’s because the Trill symbionts get to live their lives outside of the pools. And, because the symbionts can live for centuries, the Trill hosts get their accumulated skills, knowledge, and experience.

The symbiont’s personality, memories, and impulses then exist alongside the host’s. Being ‘joined’ also comes with an elevated social status in Trill society, which benefits them both.

But it wasn’t always this way. We learn the most about the Trill from Jadzia Dax, a Trill and principal character in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. But two years earlier, when we first met a ‘joined’ member of the Trill in Star Trek: The Next Generation (‘The Host’ – S4, Ep23), they not only looked different but had a relationship that leaned more toward parasitism than mutualism.

Trill ambassador Odan (Frank Luz) had a ridged forehead, typical in Star Trek: The Next Generation’s ‘alien of the week’ style storytelling. But fast-forward to Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Jadzia Dax has a human forehead and, instead, a series of spots and marks down each side of her face, neck, and body. Some fans have explained this away by saying that they were, perhaps, from different parts of Trill. But, allegedly, the show’s creators simply didn’t want to cover up Terry Farrell’s face.

The ‘joining’ of the Trill changes from Star Trek: The Next Generation to Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, too. In TNG, the Trill symbiont solely determines the personality, needs, and experiences, whereas the host takes a back seat. In DS9, the symbiont and host have equal footing after they join and then live together as one. When asked to explain how the symbiont and host brains work in tandem, Dr. Julian Bashir (Alexander Siddig) describes them “like two computers linked together” (‘The Passenger’ – S1, Ep8).

Trill as Queer Representation

I couldn’t find an official explanation for what prompted the change in the Trill between Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Sure, it could have been a continuity error, but I think that presenting the relationship between Trill host and Trill symbiont as mutual opened doors to many opportunities.

The most obvious is the storytelling potential and character development of a species built on mutualism rather than parasitism. Choose parasitism, and the creators may always have to tell an uncomfortable story that errs a little too much on the side of horror. Choose mutualism, and they can explore all kinds of themes that might arise when you put two lifeforms in the same body, like those centered on identity, sexuality, responsibility, and morality.

I believe it’s how heavily the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine creators leaned into these themes that made the Trill an interesting species to explore – an interest that endures amongst fans today. I was delighted to find that there’s still so much love online for the Trill. Many fans write about how fascinating they continue to find Trill-centred stories, and some also express how transformative Trill characters were to their own development, understanding, and acceptance.

In the online magazine Lady Science, Rebecca Ortenberg writes about the episode (‘Rejoined’ – S4, Ep6) when Jadzia Dax kisses Lenara Khan (Susanna Thompson) —whose symbionts were married to one another when they had different hosts:

“I think what I saw in Dax was less about representing someone who sometimes kissed the people that I grew up wanting to kiss but instead about something deeper, something queer in a more existential way. At that age, I didn’t think of myself as liking girls. I didn’t think of myself as liking anyone. But I felt a decided “otherness” and uncertainty with my sense of self that I saw reflected on the small screen.”

Similarly, Redditor Hylaia wrote: “When I was a teenager watching DS9, the Trill characters were the first time I ever recall being forced to think about and challenge my conception of the gender binary. It’s probably true for many others too. For DS9 to do that in the mid-90s was such a cool thing and a smart and thoughtful way to push the envelope.”

Many have explicitly read Jadzia and – from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Season 7 – Ezri (Nicole de Boer)’s stories as transgender allegories. They point to parallels between the trans experience and Ezri’s dysphoria, as well as the problems that her joining with Dax had on her personal life. There are also times when both Jadzia and Ezri correct other characters when they use their old host’s name or outdated pronouns. A great example is when Kor, a Klingon, greets Jadzia by saying: “Curzon, my beloved old friend!” Jadzia replies with, “I’m Jadzia now,” and Kor (rather than kicking up a fuss) simply smiles and says, “Well, Jadzia, my beloved old friend!” (‘Blood Oath’ – S2, Ep19)

Women at Warp writer Elissa Harris shares: “Dax, the symbiont who has lived numerous lives in various humanoid bodies… is trans. She may not be explicitly trans, but in terms of the stories that get told through her—about gender, personal change, social discomfort and assumptions based on appearances… she is very much trans […] Whether or not they intended to, the writers and performers on that show made my life better and easier in a very specific way.”

The stories told on-screen make a difference, which is why the ways creators tell them matter, too. That’s why it was so positive to see that the creators of Star Trek: Discovery cast non-binary actor Blu del Barrio and trans actor Ian Alexander in Trill roles as Adira and Grey Tal. Not only might some fans see themselves and their experiences mirrored in the Trill, but in the actors chosen to play them, too.

I rewatched an episode of Star Trek: Discovery (‘Forget Me Not’ – S3, Ep4) about the Trill when I was writing this article. There’s a beautiful scene where all of the past Tal hosts greet Adira Tal and say, “welcome to the circle”. Adira Tal now feels connected to the Tal symbiont and all of the hosts before them. This struck me as incredibly powerful, and I read it as not only a reconciling of past Trill hosts but our own reconciling of our past selves and our ancestors. I like that in each Trill, as in each of us, there can be a sense of belonging. Or, as Admiral Senna Tal says to Adira Tal: “Joining made us more than we could ever be alone.”

I don’t believe we all have to come away from every Trill episode having had a profound moment of realization or affirmation. But I do think the Trill are a special species. After their experience, Adira Tal describes the symbionts as “a gift for everyone” (S3, Ep4), and I can’t help but think they aren’t solely a gift for those in the Star Trek universe but for all of us in ours, too.

Stories of the Trill enable us to cultivate more understanding, compassion, and appreciation of difference, both in ourselves and others, rather than fear it. And this is incredibly important because no one exists in isolation. We are all living in symbiosis with each other.

This article was originally published on February 16th, 2022 on the first Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂