Star Trek fandom was in a strange place in the mid-’80s. The original series’ initial run was long gone, with fans left to sate their Trek appetite on limited TV and VHS video appearances. In cinemas, the unofficial rule regarding the movies had just begun to kick in.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) and third movie, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984), demonstrated for some the maligned ‘odd number is bad’ theory, while second outing Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) shone a lone beacon as the sole even-numbered ‘good’ entry so far. Soon, a fresh series in Star Trek: The Next Generation and the fourth movie The Voyage Home (1986) would re-invigorate the franchise. But in 1985, it was looking a bit grim for fans.

Early Star Trek Games

For gamers, it was worse. Ever since 1971, when three students at the University of California devised a text-based space strategy game on its SDS Sigma 7 mainframe computer, unofficial Star Trek games had flowed from developers eager to recreate their favorite sci-fi series without bothering about any nonsense such as an official license from Paramount. “Those computer people who happen to be Trekkies have adopted the Star Trek theme as their own,” said the description of Byte Magazine’s Star Trek listing in its March 1977 issue.

“Everybody under the sun has been programming games based loosely on Star Trek.”

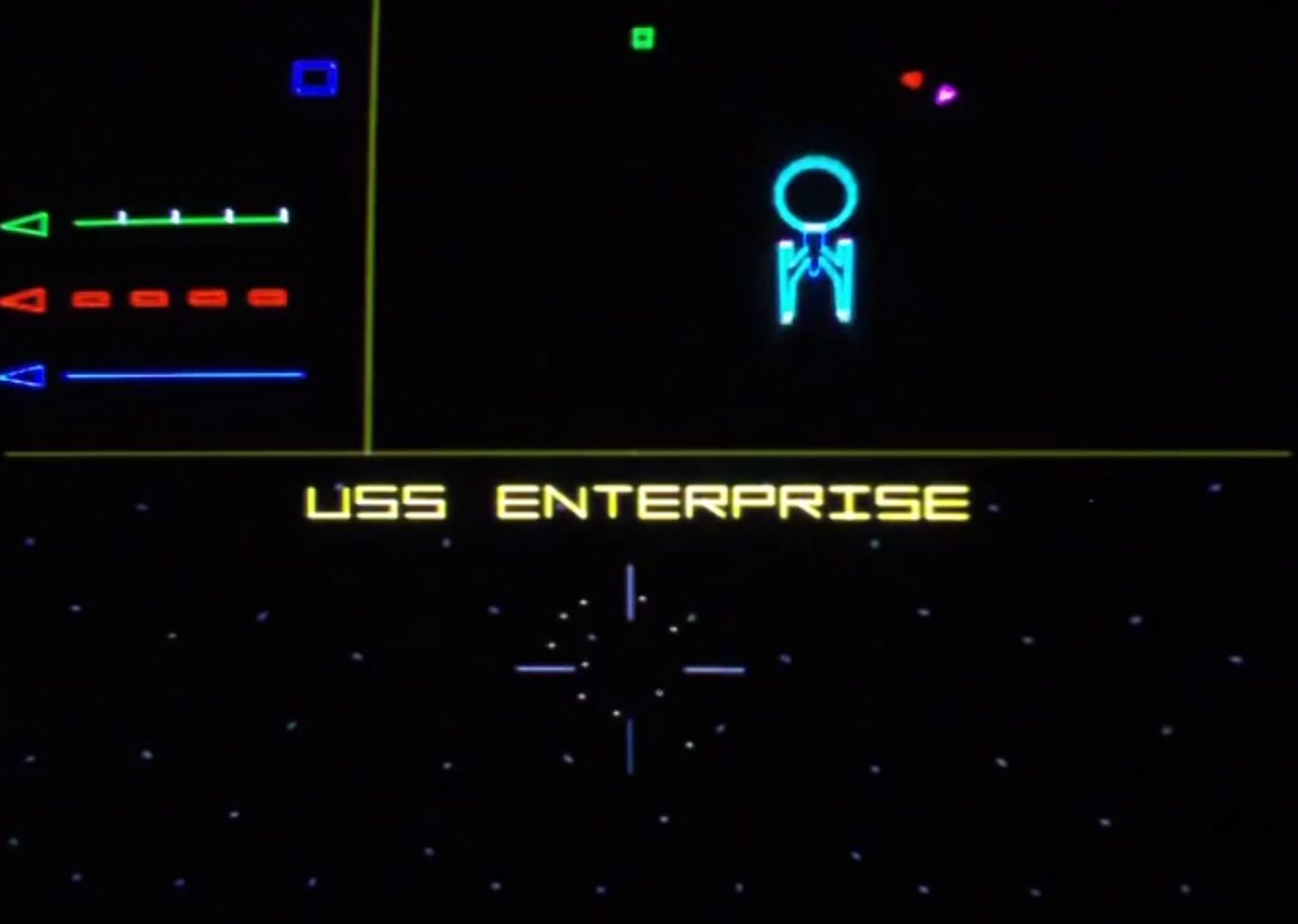

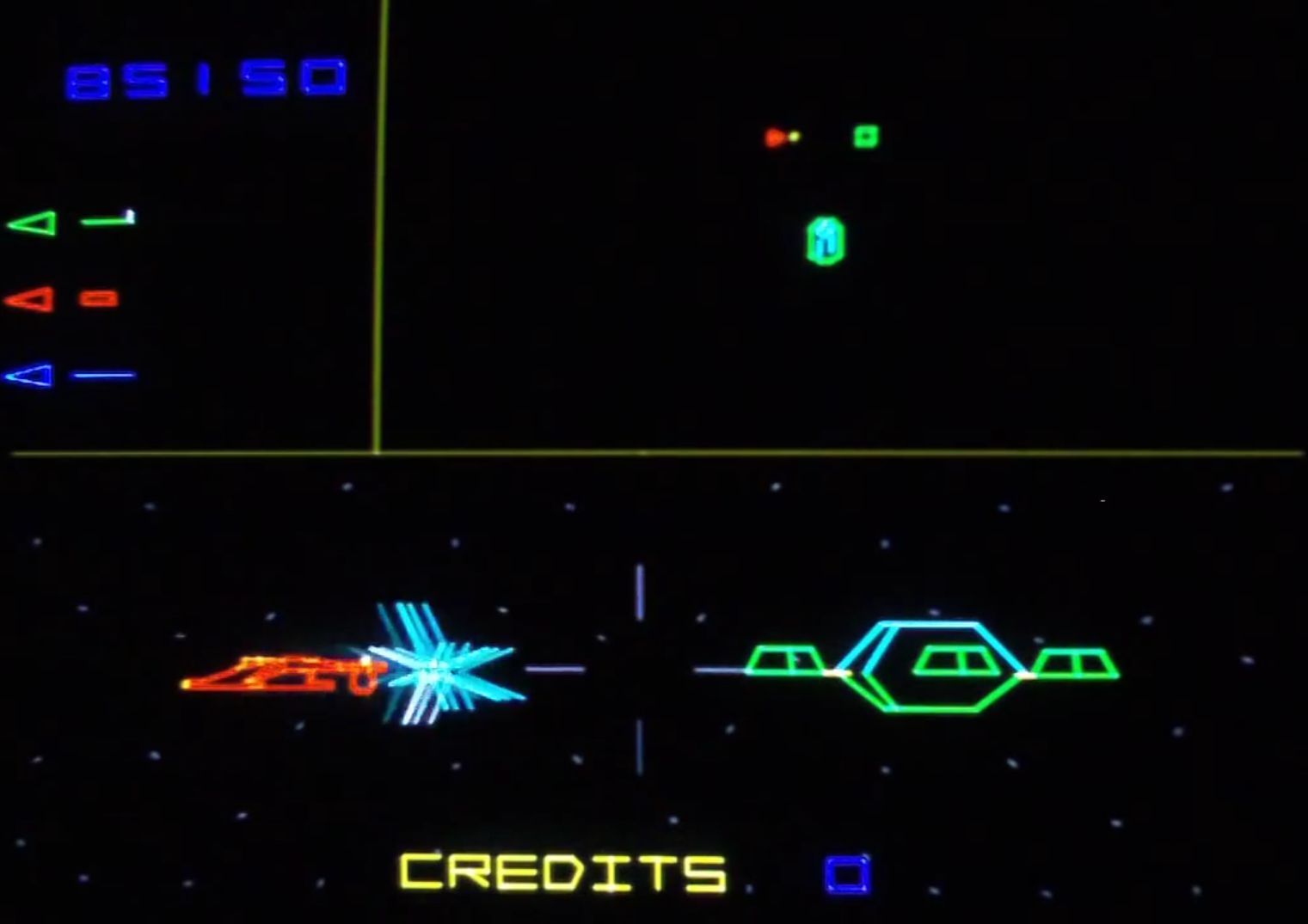

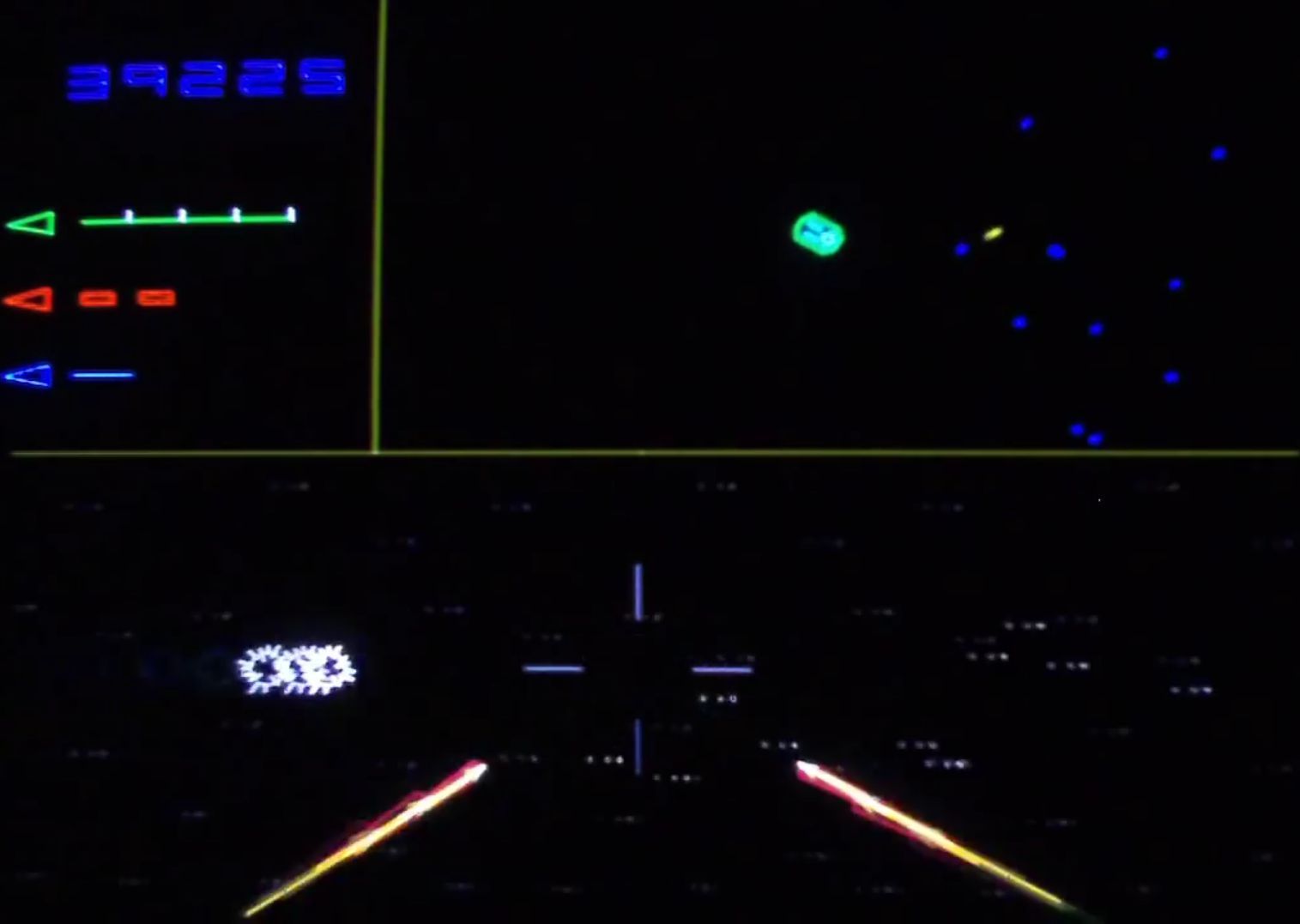

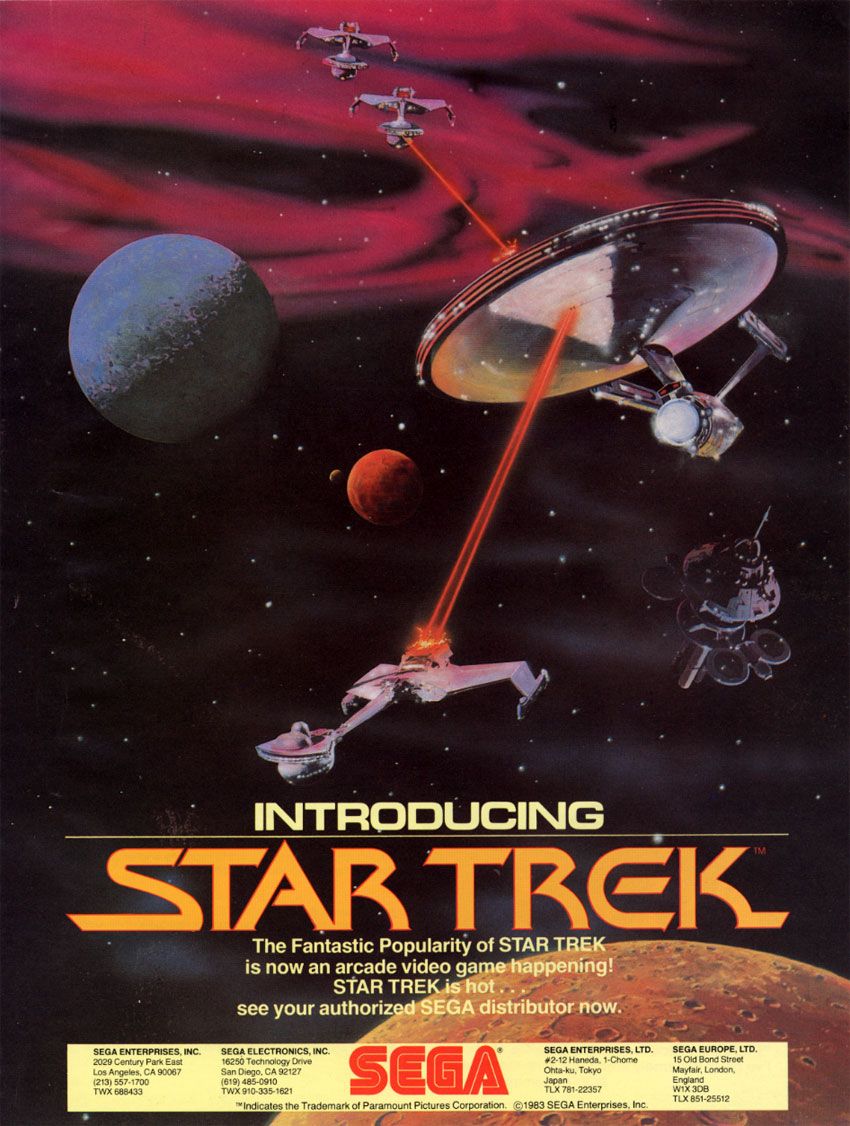

Despite a 1982 arcade game from SEGA (punchily titled Star Trek: Strategic Operations Simulator) that lent a beautifully clean vector display to the starship battles, there was precious little gaming for Trekkers during the ’80s, bar publisher Simon & Schuster with text adventures that eschewed graphics almost as much as that innocent mainframe effort from 15 years earlier. The untapped world of Star Trek waited for the game that would most do it justice: a space-based exploration story where the player combined tasks such as managing a crew, discovering new worlds, negotiating with aliens, and combating them where necessary.

In 1986, it finally came, and as with the majority of Star Trek video games up to this point, it came from the fans – and was totally unofficial.

Introducing Starflight

We warp back to 1982 and a new software company called Ambient Designs, latterly Binary Systems. Founded by Rod McConnell, the purpose of this short-lived venture was to create an ambitious sci-fi RPG for publisher Electronic Arts. The original concept for what would become Starflight was devised by genre nut Jim Yarbrough; together with McConnell the pair slowly developed the idea, enlisting technical and design help in the process.

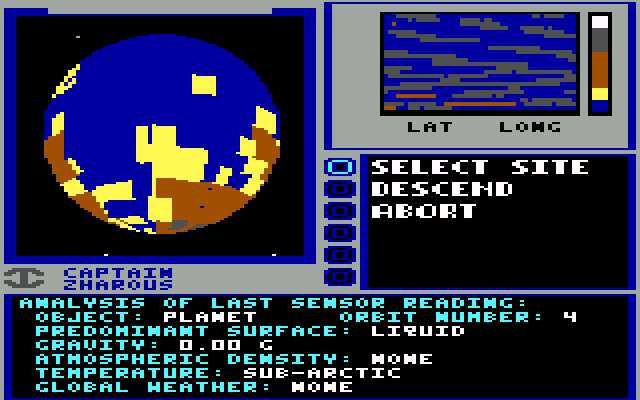

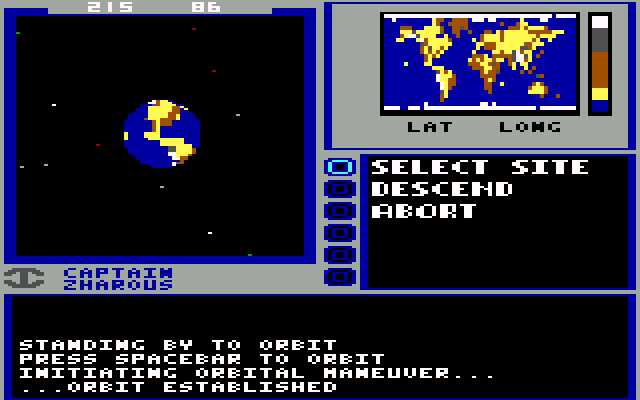

The result, released in 1986, was Starflight and it is truly a modern concept created in the mid-’80s. Taking control of a sleek starship, the player enlists and assigns the various crewmembers before exploring space as they see fit. There is no set path. The whole galaxy is open and ready to be searched, yet behind this brave new world of exploration and discovery, there’s a potentially cataclysmic event brewing. Stars are flaring up throughout the galaxy, destroying any planets within their fiery reach. Today, for fans of epic RPGs, it’s easy to trace a direct line from Starflight to the Mass Effect series in particular. In 1986, 21 years before BioWare’s hit, the common line was to a TV series from ten years earlier.

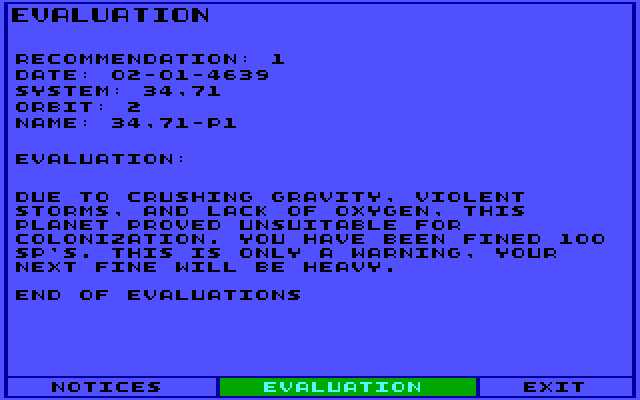

Starflight begins aboard a circular starbase orbiting the player’s familiar-sounding home planet of Arth. From here, personnel files can be created and accessed, and the important roles aboard the starship assigned. This amounts to six critical – and recognizable – positions: engineer, navigator, communications, science officer, doctor, and captain. Across the rotunda is the Interstel operations room, and starting the game will instigate an informative notice from the corporation. Here, in black type, are the instructions and primary objectives of this space adventure, and an obvious indicator of Starflight’s chief influence: “At this stage of the operation our primary goal is to gather information,” states the notice, before listing the eight goals of the mission.

“Seek out and explore strange new worlds. Establish contact with any sentients. Record alien life-form data. Bring back any valuable minerals.”

And in case you are still unsure of where all of this is heading: “Boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Further information is scant. As with Captain Kirk and the crew of USS Enterprise, this is a mission of discovery and path-finding. Knowledge, or rather the acquisition of knowledge, is the primary driver – knowledge about alien cultures, history, and the worlds they inhabit. To add an extra frisson to the mission, two previous spacecraft have disappeared and smaller scouts have begun to report back a modicum of useful information. A high density of minerals has been discovered within the mountainous region of one planet; another area, given the coordinates 135,84, has been red-flagged due to the disappearance of earlier spaceships. And most pertinently, there lies evidence of an ancient civilization inside another sector. These are the scraps of knowledge that strike a chord inside the pioneering mind as this particular space adventure begins.

And no space adventure is complete without a spaceship.