The Star Trek shows can be seen virtually all around the globe, in countries ranging from the Czech Republic to South Africa or Indonesia. The show has, since its inception in the mid-1960s, presented itself to audiences as a science fiction program that explicitly sets out to compose a future in which people of all races, species, and genders live together harmoniously.

Gene Roddenberry, the man who created Star Trek, cast himself in the role of a visionary whose quotable insights into the destiny of the human “race” became the core of the program’s market identity. Among such often quoted soundbites were, for example:

“Intolerance in the 23rd century? Improbable! If man survives that long, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures.” - Gene Roddenberry, qouted in The Making of Star Trek (1968).

Or

"Diversity contains as many treasures as those waiting for us on other worlds. We will find it impossible to fear diversity and to enter the future at the same time." - Gene Roddenberry, quoted in Creating The Next Generation (1995).

Star Trek’s effort to construct for itself a multicultural image can be traced to primarily two strategies. First, the program has been striving for a diverse cast of characters, from The Original Series featuring a Black woman and an Asian man among its bridge crew, to Deep Space Nine and Voyager showcasing an African American (male) and a (White) female in their respective captain’s seats. The second strategy lies in the kinds of stories Star Trek chooses to tell. With reliable regularity, the program features self-conscious ‘issue’-episodes that are obviously designed to tell a parable on current political issues.

These episodes follow a typical pattern in projecting real-life racial (or other) issues onto alien species. In ‘Let That Be Your Last Battlefield’ (TOS – S3, Ep15), the crew of Enterprise encounter the humanoid alien Lokai, whose face is half black and half white, and who is apparently on the run in a stolen shuttlecraft. Soon, a law enforcement officer, Bele, comes hunting after Lokai. The two look exactly alike, only Lokai is white on the right side of his body and black on the left, while Bele’s colors are distributed the other way around. When Lokai urgently pleads with the Enterprise crew to grant him political asylum, they learn that the aliens’ planet is riven by a deadly race war, a war which, by the episode’s end, will have killed all life on the planet. When confronted with the madness of ultimately genocidal hatred, the crew of Enterprise tries to make sense of it by putting the conflict in the context of their own (human) history:

Chekov: There was persecution on Earth once. I remember reading about it in my history class.

Sulu: Yes, but it happened way back in the 20th century. There is no such primitive thinking today.

- ‘Let That Be Your Last Battlefield’, The Original Series – S3, Ep15.

The episode is thus able to address the late 1960s’ reality of brutal race riots in a safe and unthreatening context. It simplifies the complex structure of race relations by locating the source of all tensions in each race’s dislike of the other’s physical appearance, a difference the episode seemingly strives to make as superficial and ludicrous as possible. The dialogue between Chekov and Sulu then affirms that humanity has long overcome this state of racial prejudice, thus casting themselves in a role of enlightened superiority. In striking similarity to the (ideo-)logic of the colonial encounter, the crew of Enterprise attempt to educate and save the “primitive” aliens, yet they remain unsuccessful. The episode concludes with disquieting and unresolvedly painful images of an eventually genocidal race war.

Considering this general representational practice, the rare cases in which Star Trek does not follow its own rule deserve particular attention. One such exception is that Star Trek addresses one, and only one, ethno-racial group directly—Native Americans.

Paradise Lost

Star Trek’s choice becomes even more interesting when one takes into consideration that the program explicitly hails from the cultural tradition of the Western—both Roddenberry’s oft-quoted description of Star Trek as “Wagon Train to the stars” and TOS’ and The Next Generation’s designation of space as “the final frontier” in their respective title sequences evidence this cultural association. Indigenous Americans emerge from this context as a group that evokes a highly idealized and distorted image of one period in American history, mostly set in the 19th century, that mainstream American culture nostalgically yearns for as a cultural scenario that epitomizes ‘America’ like no other. On the other hand, however, Native Americans also represent the United States’ history as a colonizer, a history the cultural narratives of the frontier repress just as vehemently as Star Trek represses the colonial implications in its own interstellar “exploration.”

Three episodes cover the whole range of Star Trek’s representation of Native Americans from the earliest instance in Star Trek: The Original Series to Star Trek: Voyager’s recurring Native American character, Commander Chakotay. First, in TOS ‘The Paradise Syndrome’ (S3, Ep3), Enterprise arrives on an alien planet, where an accident wipes out Captain Kirk’s memory. He is soon after found by the planet’s inhabitants who resemble Earth’s Native Americans. Due to the circumstances of Kirk’s sudden appearance, the tribe takes him for a god and adopts him into their community. The amnesic captain, taking on the name ‘Kirok’ for a time enjoys the simple life, he gets married and is happy to learn that his wife is pregnant. After a while, however, the tribe finds out that ‘Kirok’ does not have supernatural powers, and they stone him and his wife. At the last minute, Enterprise, having finally found its Captain, steps in and beams the two away from the site of their execution, yet while Kirk can be saved, his wife and unborn child die.

Although standing apart from the other, later episodes featuring Native Americans which are all linked through a common narrative thread, the episode introduces important aspects of Star Trek’s representation of Native Americans, a representational practice that quite clearly continues traditional Western image-making of the ‘Indian’. The Native American tribe (inspired to some extent by the popular image of the Sioux people), whose presence the narrative rather clumsily explains as being brought there by some mysterious aliens who wanted to save them from extinction, serves as the symbolic counterpoint to the technologically and socially advanced life on a starship. The social ‘evolution’ Star Trek so stresses for humanity seems not to take place within Native American culture—the tribe’s way of life in the 23rd century still resembles that of the 19th century.

The image the episode draws of Native Americans clearly hails from the racist notion of the ‘noble savage’ – the ‘positive’ version of the Western image of the ‘Indian’. It entails a romantic yearning for the simple life Native Americans come to represent, a life decidedly free of technology and complex social structures, while at the same time marking that way of life as clearly inferior (and therefore doomed to extinction).

The episode evokes this inferiority in several ways, employing well-established cultural strategies. For example, it is quite typical that the White individual coming into the Native American tribe ‘naturally’ takes on a leadership position, thus implying that, even without any of the institutional power he might be able to draw on in his ‘civilized’ life, his superiority is so obvious that even the ‘native’ notice it. In addition, the apparent lack of social development the episode implies also designates Native Americans as inferior to humanity as imagined by Star Trek. This aspect of the tribe’s image is particularly important, not only because it makes Native Americans different from the core group in Star Trek’s most central social quality, but also because it rules out the possibility of Native Americans ever joining the core group. A community that is unable to adapt to changing social and technological conditions, it seems to be the lesson in Social Darwinism the episode inevitably entails, will have to die sooner or later.

Fellow Travelers

Taking the highly conservative ‘The Paradise Syndrome’ as a point of reference, it is interesting to look at the ways in which subsequent episodes both perpetuate and change Star Trek: The Original Series’ representational practices. Chronologically, the next episode is The Next Generation’s ‘Journey’s End’ (S7, Ep20), in which Enterprise is ordered to remove a community of Native Americans from a planet on which they had settled. This time, the episode gives a more elaborate explanation of the tribe’s presence on the alien planet: The community left Earth many years ago in order to search for land where they could build a new home. The episode makes clear that the Native Americans had to go on that journey only because they had been robbed of their homeland and that they were looking not just for any piece of land but for one with which they could enter a spiritual relationship as they had done with their original homeland.

Looking more closely at the role in which the episode casts Native Americans reveals a highly interesting colonial narrative. ‘Journey’s End’ is able to address colonialism directly—an issue it uneasily strives to reject in the subplot concerning Captain Picard — only in a narrative that, first, draws on the Native Americans’ role in a historical colonial encounter, and that then imagines a scenario in which it reverses that role. More specifically, the episode can only develop a convincing narrative of a colonizer who refuses to give up the land of which he has taken possession by casting a group in the role of the colonizer who has previously undergone the experience of being colonized. Within Star Trek’s multicultural framework, Native Americans emerge as (possibly) the only group who can explicitly act as colonizers and still motivate audience sympathies.

There is another subplot in ‘Journey’s End’ that points to a second narrative function Native Americans serve in Star Trek’s contemporary multicultural economy. When Enterprise becomes involved in the business of re-locating the tribe, Wesley Crusher, the son of the ship’s doctor, happens to be on board. Currently training to become a Starfleet officer, Wesley is in a deep personal crisis concerning what he wants to do with his life, a crisis that manifests itself in rebellious behavior against authorities as well as against his friends. A member of the Native American tribe takes interest in him, who later turns out to be the alien ‘the Traveler’ who had predicted for Wesley an extraordinary future several years ago and who had now returned to take Wesley with him on a search for new levels of existence.

Significantly, then, this alien, who represents one of Star Trek’s most esoteric storylines, chooses a Native American identity to motivate the discontent white teenager Wesley Crusher to pay attention to his spiritual self. Even more so, once Wesley has made the decision to join the Traveler in search for places “where thought and energy meet,” the alien instructs Wesley to begin his studies in the Native American community because they supposedly have special insights that could lead him on the right path.

Native Americans clearly take up the function of spiritual mediator here. They fill a void in the image of Star Trek’s core group, which the program so insists on imagining as rational and forward-looking that there seems to be no room for developing a spiritual identity. This phenomenon allows two conclusions concerning Trek’s representational politics. First, it points to contemporary multiculturalism’s need for spirituality, a need that apparently grows more urgent the more the multicultural core group stresses its own tolerance, which is a decidedly rational concept. Second, it illustrates how multiculturalism is still incapable of fusing that spirituality and rationality.

Spirituality needs to be represented by some ethnic Other, a role, Star Trek demonstrates, that Native Americans still fit exceedingly well. The fact that the rational self can never be spiritual, however, inevitably implies that the spiritual Other also cannot be rational. This conclusion not only imposes itself by conversion, but also because, otherwise, the Other would be superior to the member of the Eurocentric core group, a hierarchical distribution Star Trek’s evolutionary logic has certainly not intended. Traditional White images of the ‘Indian’ silence any suspicions of aboriginal superiority by making sure to mention the natives’ impending genocide, a narrative element that not only produces the sentimental effect but also clearly states that spirituality is a luxury in the evolutionary struggle for existence.

A Cuchi Moya

Although Star Trek seems to be aware of the ludicrousness of a Native American culture that remains unchanged through centuries of dramatic social and technological development, the program still cannot shed the mutually exclusive logic of rationality versus spirituality. Already ‘Journey’s End’ attempts to update the Native American culture it imagines by having the members of the tribe not just encounter their own spirits in their vision rituals but also the gods of other species. The effort to portray a Native American culture that convincingly fits in the 24th century becomes even more obvious in the context of Commander Chakotay.

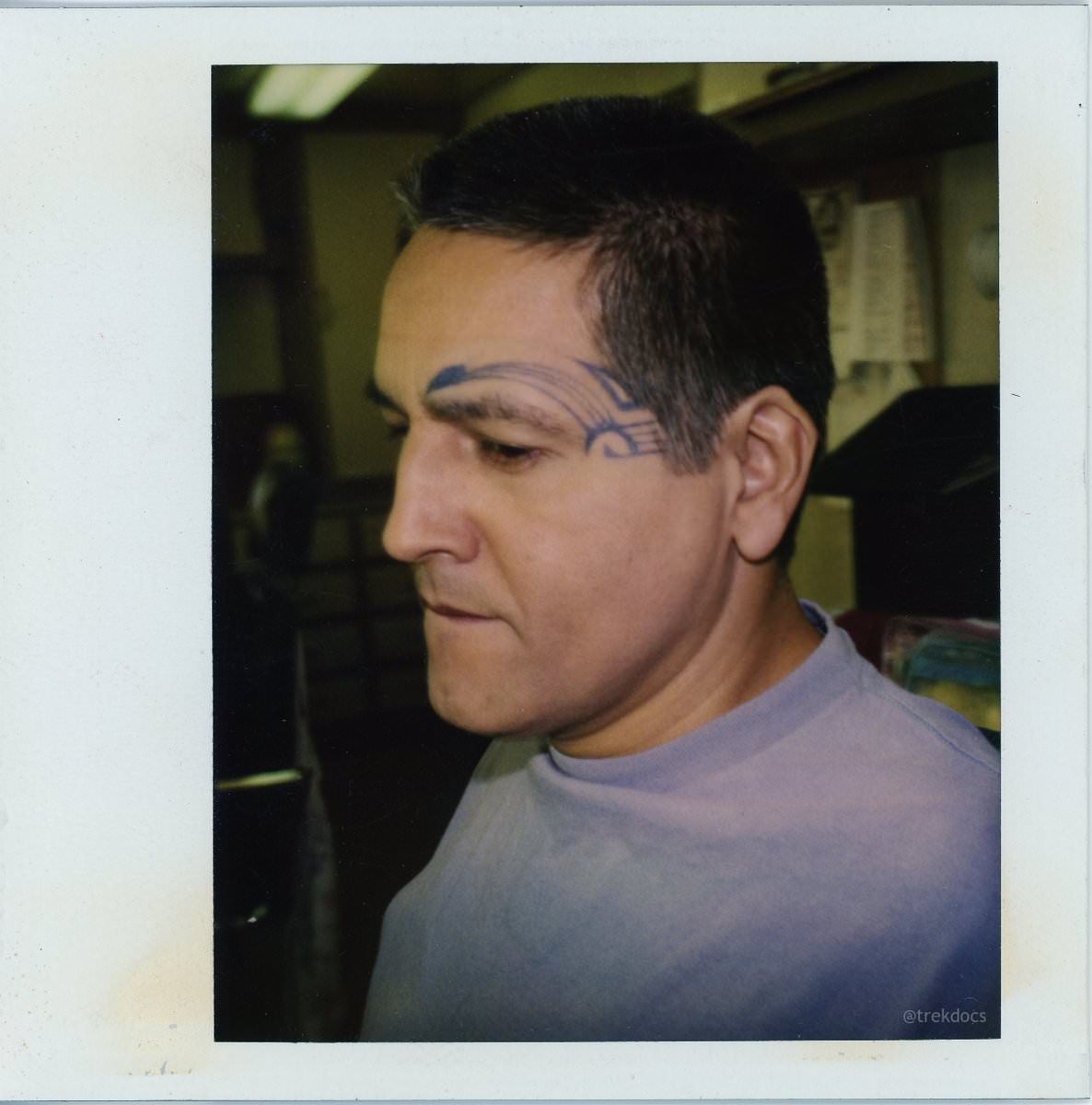

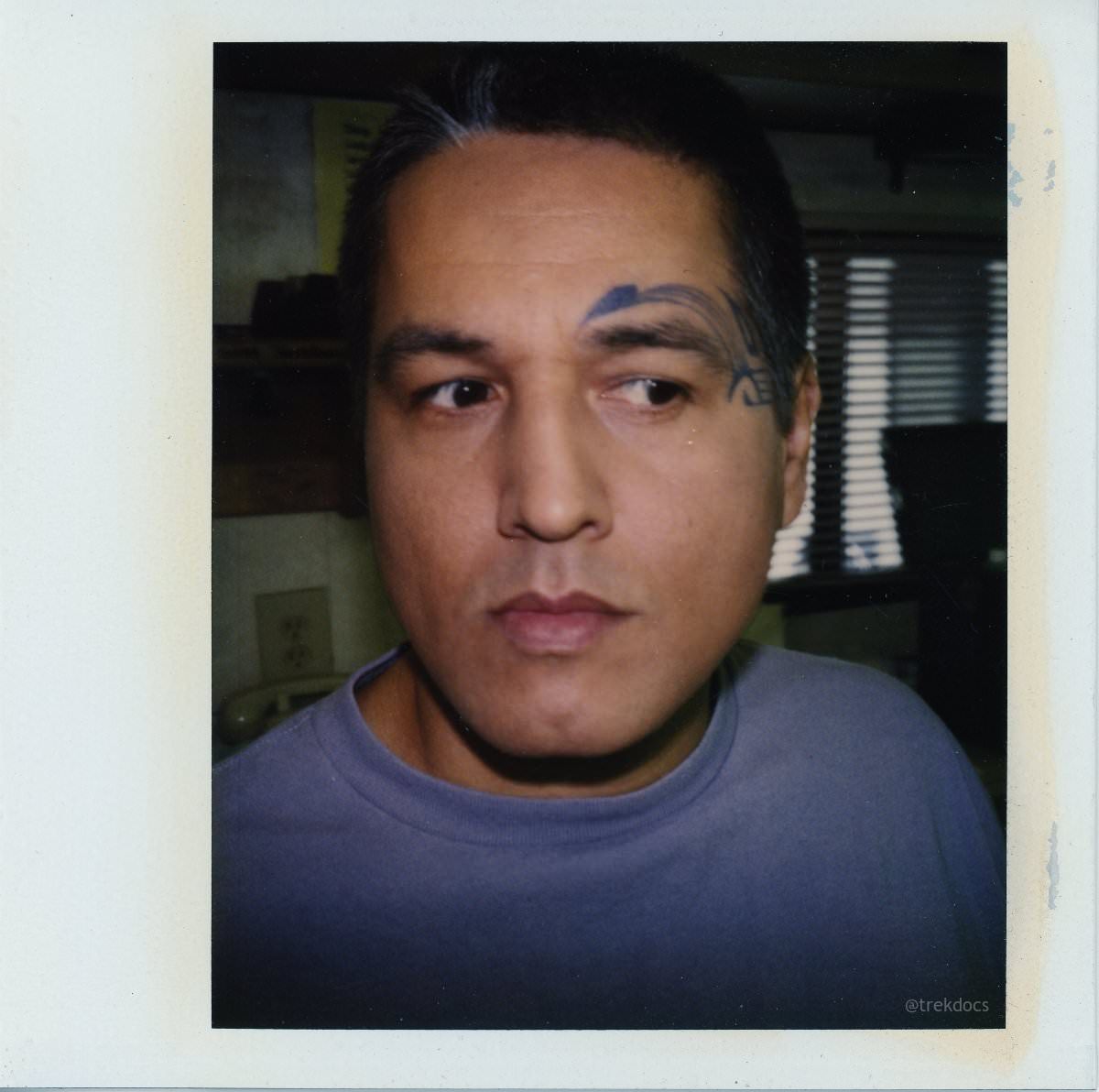

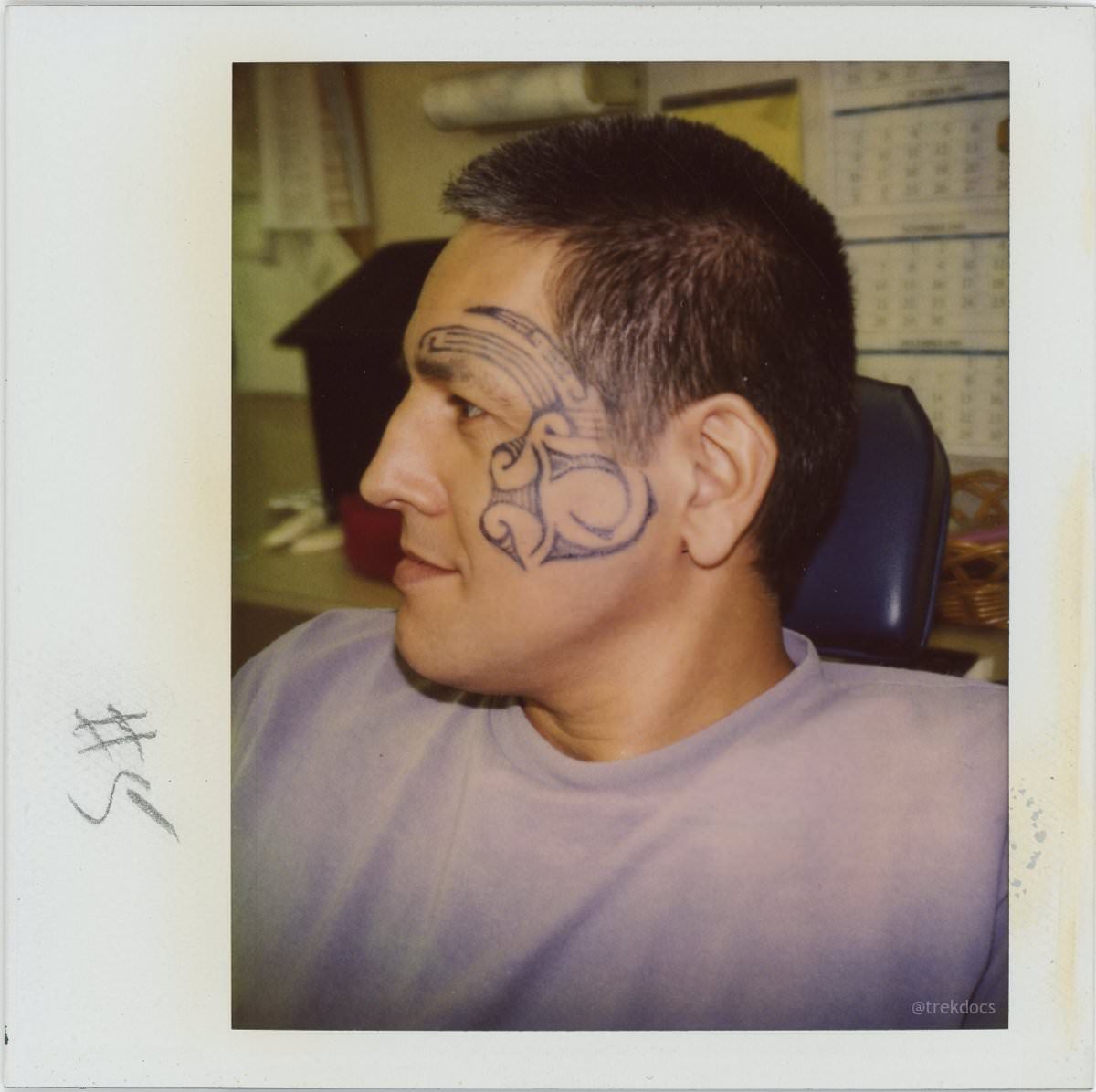

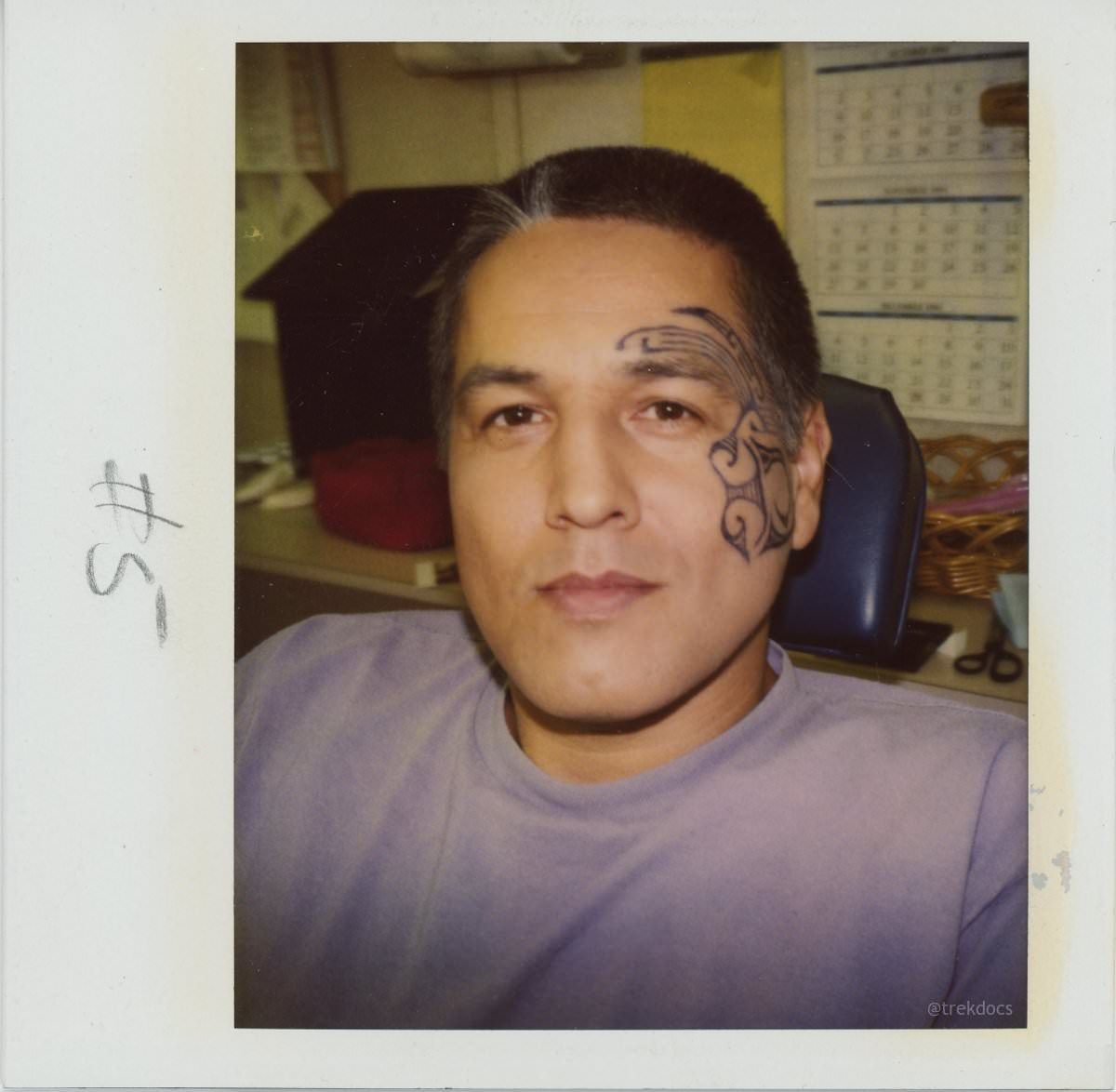

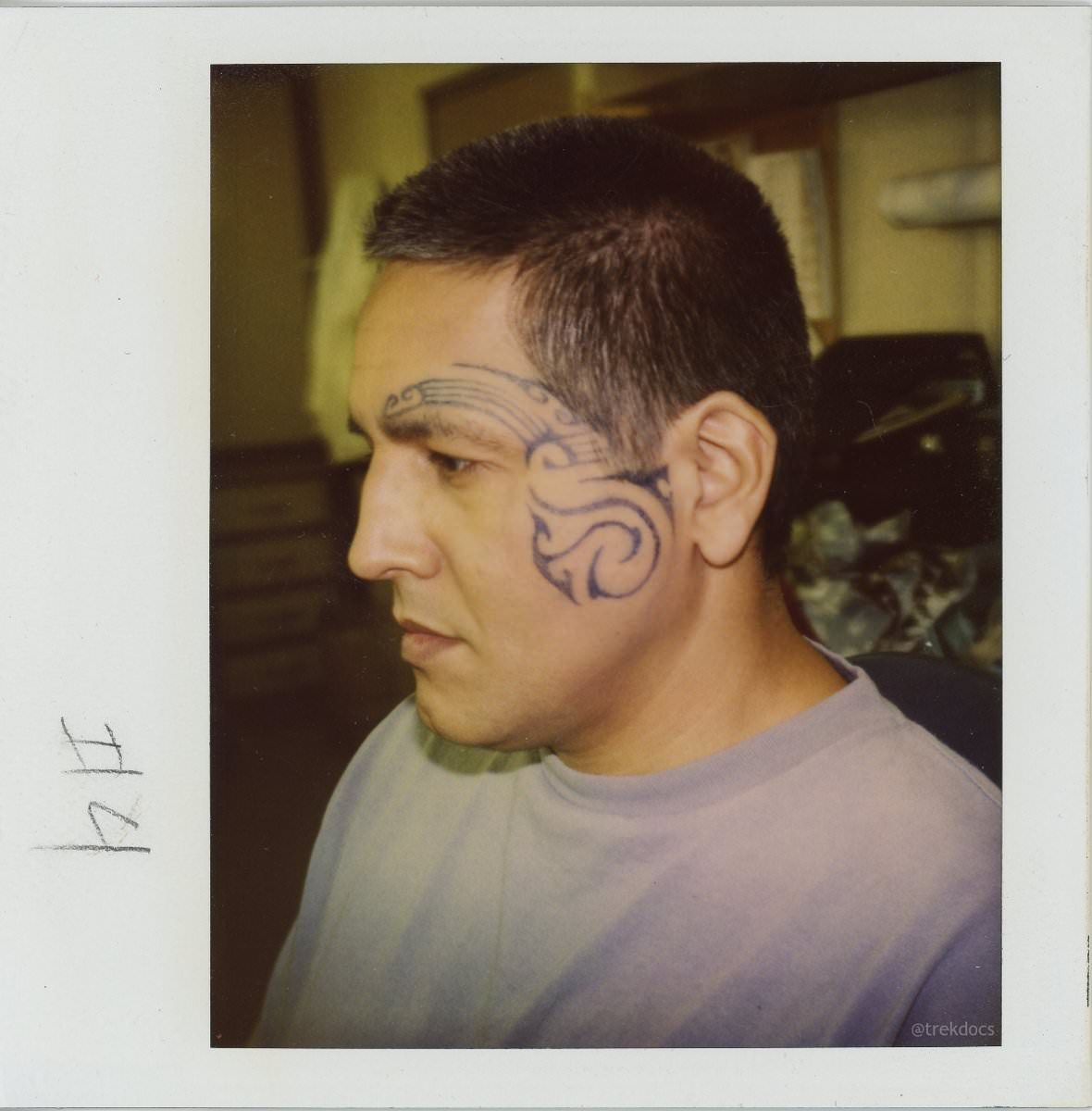

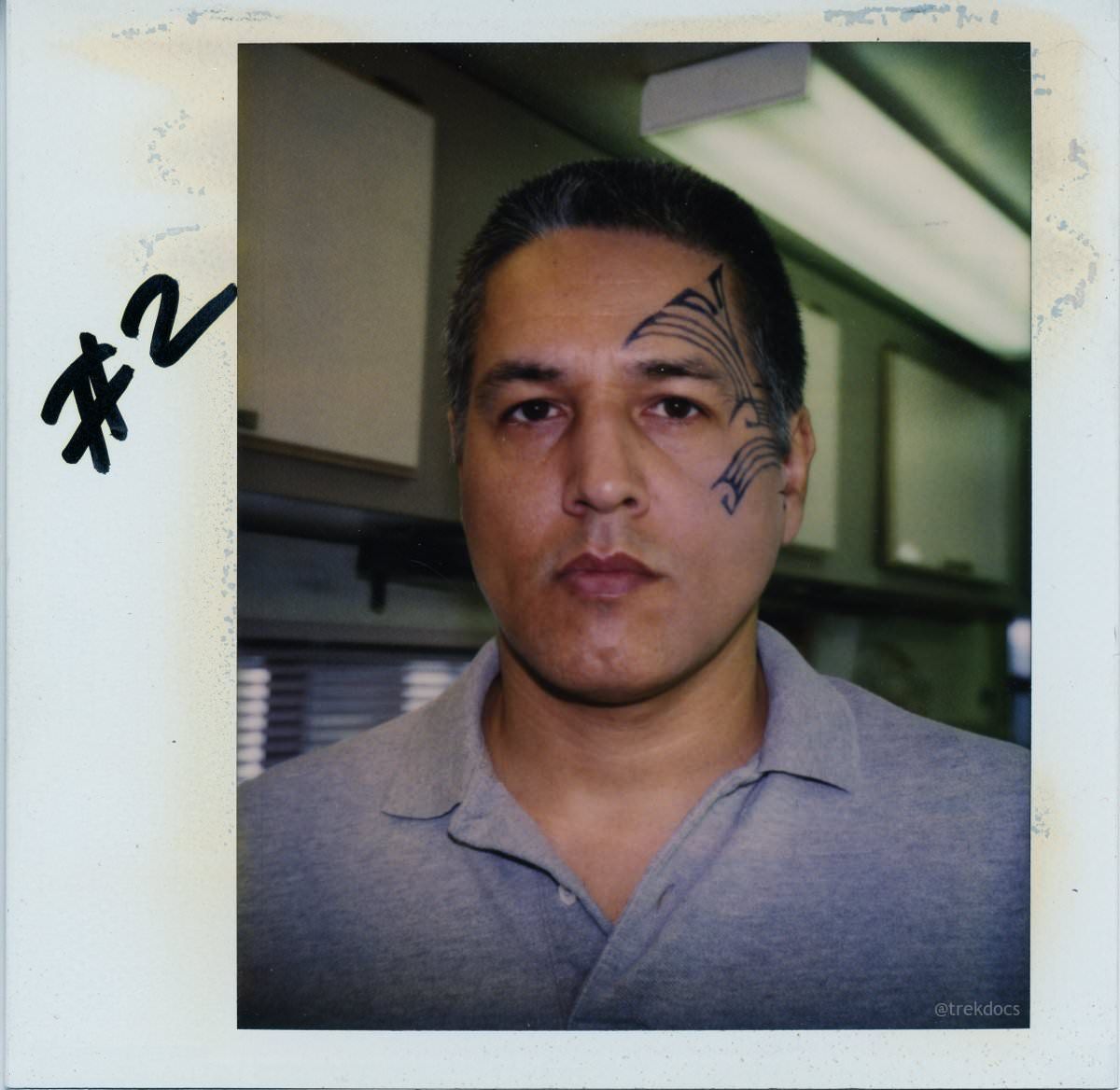

That Voyager character initially does appears to personify the synthesis of rationality and spirituality: He is a Starfleet officer, obviously capable of functioning in such a highly advanced environment, yet he holds on to his ‘Indian’ roots. This synthesis particularly manifests itself in the character’s visual appearance, wearing a Starfleet uniform yet having his ‘Indianness’ marked by a facial tattoo. Counterbalancing this interesting visual coding, however, is Chakotay’s recurring narrative function as, again, the ship’s spiritual authority. Whenever Captain Janeway is in doubt concerning the decisions she has to make, she consults with Chakotay to, quite literally, borrow his spiritual helpers.

Cliches mark these vision quest scenes as extraordinary, standing apart from the rest of Voyager’ the ritual words Chakotay speaks, ‘A Cuchi Moya’, remain in what appears to be his native language—a rather surprising phenomenon considering Star Trek’s ever-present Universal Translator which automatically translates even the most distant alien language into convenient English—and the scenes are accompanied by a specific musical theme featuring panpipes, an instrument most popularly associated with South American Indians. The scenes thus not only establish a clear contrast to the program’s otherwise ‘rational’ storylines, but they also employ, again, well-worn imagery to evoke romantic stereotypes of the ‘Indian’. Although Star Trek: Voyager hence makes an explicit effort to draw a more nuanced picture of Native American spirituality, the program is still unwilling to complicate the binary of the spiritual versus the rational.

The character of Chakotay also surfaces another problematic aspect of Native American representation: casting. For much of film and TV history, producers (until quite recently) frequently hired white and Asian actors to play ‘Indian’ roles, and if they did cast Native American actors “for background action,” they did so completely insensitive to tribal affiliations.

When developing the figure of Chakotay, Voyager‘s producers seemed to have been aware of these as well as other flaws in traditional representations of Native Americans, and they were apparently determined to draw a more correct image. This effort becomes evident in that the Voyager production team not only hired a science consultant—as had been the rule since The Next Generation—but that they also hired an expert, Jamake Highwater, to check each script for accuracy concerning Native American issues. Despite such obvious efforts not to repeat the ignorant white images of Native Americans of the past, Voyager did perpetuate traditional patterns in casting the character of Chakotay.

First of all, while clearly striving to mark Chakotay as Native American, writers and producers seemingly regarded the character’s tribal affiliation as only marginal to the figure’s identity. Initially, Chakotay’s tribal ancestry remained unresolved for a long time. It was then decided upon as Sioux (the Plains Indian again), to be soon after changed to Hopi, to be finally left open again. Indeed, Voyager began employing the character of Chakotay as precisely that kind of generic ‘Indian’, referring to him only as being “‘from a colony of American Indians.’” One contributor to the <native-l@csd.uwm.edu> discussion group summarizes many viewers’ dissatisfaction with seeing, once more, a generic ‘Indian’:

[…T]he show can be faulted for not creating a tribal identity for Chakotay, which would help frame him a little better. All we know about his culture is that he has a tattoo, a spirit guide, and uses a machine to imitate the effects of peyote. Also, haunting, “native” reed in-struments play on those rare occasions we get to see his private living space […].

It was not until audience pressure concerning another representational faux-pas forced the production team to write a specific tribal heritage into the character that this generic ‘Indian’-ness abated.

This second faux-pas concerns the actor cast to play Chakotay. Robert Beltran is Mexican-American, and although he tried to justify his playing an ‘Indian’ role by evoking the Mestizo (mixed European/indigenous) heritage of many Mexicans, many viewers experienced his presence as “yet another non-Indian actor […] in a part that is identifiably Indian and uses trappings from the culture.” Only very gradually, and at Beltran’s own suggestion, did the producers effectively solve the problem of their own casting decision by specifying Chakotay’s tribal affiliation as “south of border”, i.e. Mayan, Aztec, or Inca.

Back to Basics

Although Voyager explicitly sets out to draw an image of Native Americans that satisfies the audience’s heightened sensitivities regarding representation, the program clearly fails in its own project. In this context, it is ironic that the only moments in which Voyager does lastingly disrupt traditional representational politics lie outside of the type of self-conscious multicultural discourse to which Star Trek usually subscribes. This is achieved when Voyager uses humor to address stereotypes of Native Americans. Two such instances exemplify the mechanisms at work. First, in the pilot episode, ‘The Caretaker’ (S1, Ep1), Tom Paris tries to save Chakotay’s life in an extremely tight situation. While Chakotay attempts to dissuade Paris from risking his own life, Paris jokes about how, if he succeeds, Chakotay would be forever in his debt.

Chakotay: You get on those stairs, they’ll collapse! We’ll both die!

Paris: Yeah? But on the other hand, if I save your butt your life belongs to me. Isn’t that some kind of Indian custom?

Chakotay: Wrong tribe.

- Star Trek: Voyager, ‘Caretaker’ – S1, Ep1.

Second, in the two-part episode ‘Basics’ (S2, Ep26-S3, Ep1), Voyager falls into the hands of the hostile Kazons, who maroon the crew on an inhospitable planet. Being robbed of all their technology, the crew has to struggle with the most quotidian problems in order to survive. They, first of all, try to make a fire. When they remain unsuccessful for a long time, Chakotay remarks dispiritedly that he was the only Indian for light-years around and not even capable of making a fire.

In both these scenes, humor is used to relax a tense situation. The scenes do not set out to address Native American culture, they rather evoke ‘Indianness’ in a merely functional way, almost incidentally. In order to achieve this effect of relaxation, the scenes bring up specific stereotypes of Native Americans, which the ‘real’ Indian Chakotay then proves wrong. He does that, in the first scene, by pointing to the great diversity of existing Native American cultures in contrast to the generic ‘Indian’ culture the stereotypical image holds on to, and in the second scene, by demonstrating that the skills stereotypically ascribed to Native Americans belong to a specific historical environment and that they do get lost once they are no longer practiced.

The scenes are effective in challenging the logic of traditional image-making for two reasons. First, they manage to address and effectively critique central problems in the cultural image of the ‘Indian’ which Star Trek: Voyager could not prevent itself from repeating. And, second, the critique works in these scenes precisely because they leave the self-conscious multicultural mode the series otherwise adheres to. The scenes are among the few moments when Star Trek allows itself to acknowledge the existence of cultural stereotypes among its own core group, something the program is only able to do—without disrupting Star Trek’s very premise—in a humorous mode. The laughter these scenes produce allows the core-group-identified audience to interrogate their own prejudice in a context that is unthreatening yet that clearly endorses the Native American point of view, as, to put it casually, the laughs are on the ignorant.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂