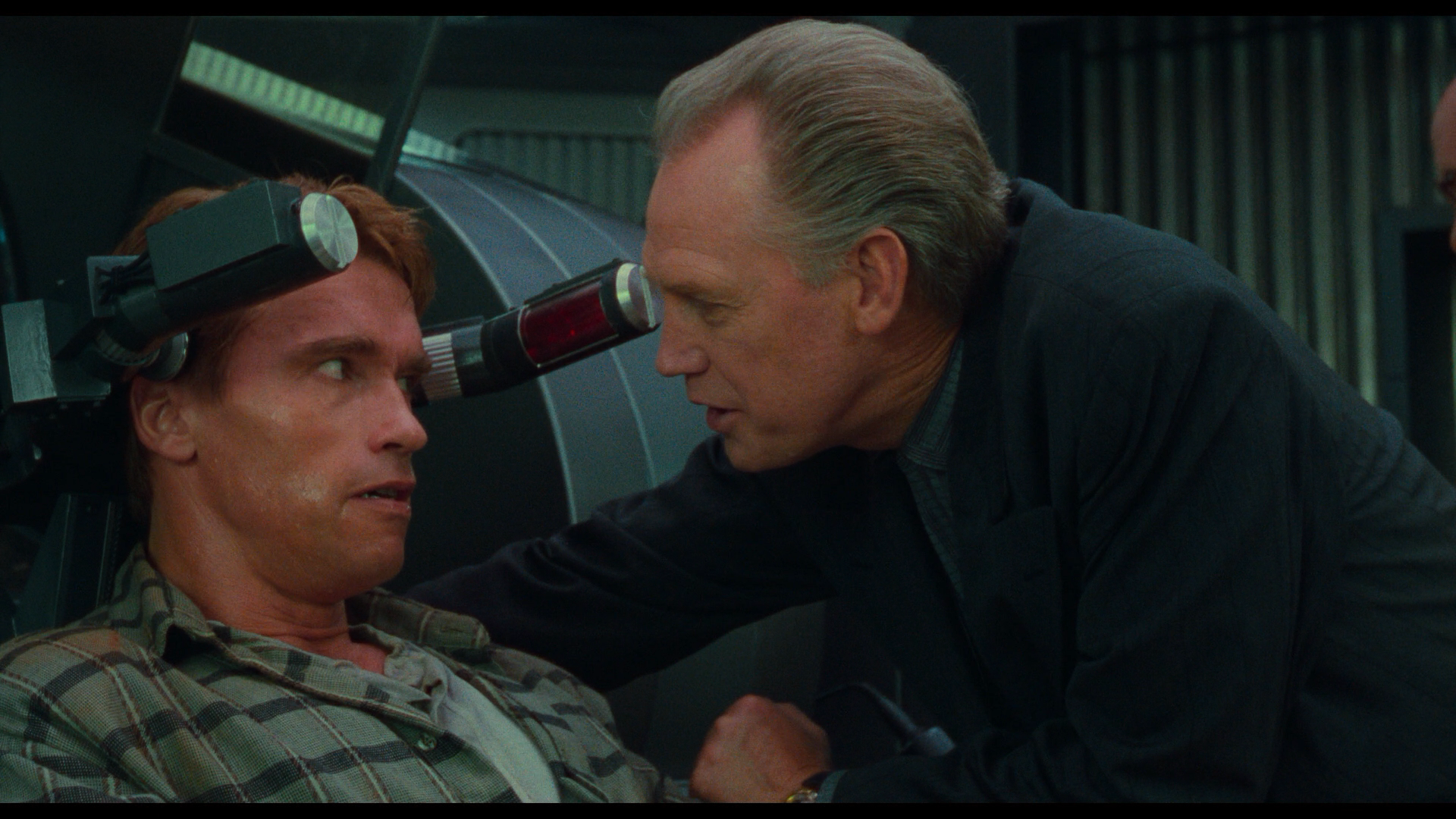

Despite 20 years of frontline psychiatry, I am still yet to diagnose a Schizoid Embolism in any of my patients… but of course, it only exists (so far), within the rich world of Total Recall. The 4K Blu-ray version of the 1990 Paul Verhoeven film has finally been released. This creates a timely opportunity to consider the psychopathology demonstrated in the film and also consideration of the troubles of the source author: Philip K. Dick (PKD), whose 1966 short story We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, provided the inspiration for the screenplay.

Amanda Tapping: Embracing Mental Health as a Fandom starts at 11 am PDT/2 pm EDT/7 pm BST, and will last for one hour.

Get your ticket from jointhegreenroom.com.

This seminal 1990 film went on to influence such classics as The Matrix (1999) and Inception (2010) and is even more remarkable when you consider it was made largely without using CGI. The 2012 remake with Colin Farrell is somewhat less iconic despite the casting of the luminous Kate Beckinsale as Quaid’s wife, but of course, she is no Sharon Stone.

Psychiatrists are advised not to diagnose those they have not mentally examined and so let’s simply consider the life of PKD and what events may have influenced his writing genius. He was born in 1928 with a twin sister Jane, who tragically died at six weeks of age. Of note the gravestone was also inscribed with his name at her burial; for the next 53 years of his life his funeral plot was secured, only the final date to be added.

We know that twins have a unique bond, after all, they shared the same womb, and PKD’s work often references the phantom twin, normally depicted as simulacra. Does this mean PKD was in touch with his Thanatos? This is the ‘Death Instinct’ described by Freud as “the goal of all life is death.” Perhaps PKD truly had a lifelong understanding of that, writing in his introduction to The Golden Man (1980):

“I want to write about people I love, and put them into a fictional world spun out of my own mind, not the world we actually have, because the world we actually have does not meet my standards.”

And so wrote the man who divorced five times by the age of 45. PKD’s private life was equally as fantastical as his books; allegedly he attempted to push his third wife, Anne, off a cliff in a car in 1963, and she was then later involuntarily committed to an asylum with his petitioning. Then after divorcing her in 1964, he attempted to commit suicide by driving off the road with his then-girlfriend, Grania Davis as his passenger; he certainly wasn’t ideal boyfriend material. Two further marriages followed and other suicide attempts, on a background of a man who was a consistent user of psychoactive substances.

Philip K. Dick’s Substance Abuse

No consideration of PKD’s persona can ignore his habitual use of illicit drugs. His substance of choice was amphetamines (speed – a potent psychostimulant) and many have observed that it probably enhanced and fueled his prolific output of material: over 40 novels and 120 short stories. But from a psychiatric point of view, the phantasmagorical worlds he created suggested an author who was very familiar with hallucinogenic drugs.

Neuroscience has shown that creative processes can be enhanced with the removal of the brain’s normal cognitive dampeners, hence the current trend of “micro-dosing” of LSD amongst programmers in Silicon Valley, but PKD claimed to only have tried the substance once. Perhaps he was fortunate, as overindulgence could have resulted in a Syd Barrett-like incandescence of his creative flame.

Amphetamines are potent releasers of dopamine (a neurotransmitter), which will induce psychosis in anyone if enough is imbibed. In February 1974 PKD had what he considered a profound experience in his understanding of the world when he observed light reflecting off a woman’s necklace who stood at his doorway, creating a “pink beam” which fell upon him.

He described weeks of hallucinations in a 1979 interview with Charles Platt:

“I experienced an invasion of my mind by a transcendentally rational mind, as if I had been insane all my life and suddenly I had become sane.”

As a psychiatrist, this is interpretable as a “delusional perception,” a normal percept with a delusional interpretation, characteristic of psychosis. But what actually is psychosis? It is experiencing a distorted reality with hallucinations, such as voices when no one is there, and delusions, un-understandable ideas that usually have the individual self at the epicenter of the belief. Psychosis is common, about 1 percent of the population will experience it. We know there is a genetic element – it can run in families – and it can be precipitated by drugs or substances that affect dopamine levels in the brain, and episodes of stress.

PKD said that 1977’s A Scanner Darkly was the first book he wrote without the assistance of amphetamines; indeed, it partly features a semi-autobiographical account of his own drug rehabilitation. This was memorably filmed in 2006 using Rotoscoping (a type of animation superimposed on live-action footage) that featured Keanu Reeves as a drug enforcement agent. But perhaps his most prodigious work on illicit drugs is The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (written in 1965), which features his trademark exploration of layers of reality with an intergalactic drug dealers’ war bolted on.

It also features a personal hero of mine, the psychiatrist Dr. Smile who provides therapy, through the medium of a portable suitcase, that is employed to ensure the protagonist, Barney Mayerson, fails the psychometric testing needed to become a Martian colonist. PKD consistently depicted the prospect of being a colonizer as a dismal affair, which could only be made bearable by escaping to alternate realities with illicit drugs.

Philip K. Dick’s Final Decade

We do know PKD was a poor house guest. While he was speaking at the Vancouver Science Fiction Convention in February 1972, Michael Walsh (a local movie newspaper critic) invited him to stay in his home, but after two weeks he was kindly asked to leave due to his chaotic behavior, with Walsh memorably describing PKD as an ‘alien being’. At one point Walsh played PKD a record that contained assorted dialogue and jumbled sound effects; this provoked a catastrophic reaction in PKD who reportedly said:

“Turn it off! Turn it off! It sounds like the inside of my head!”

This trip was the beginning of PKD’s eventual path into drug rehabilitation.

There is so much more about PKD we could consider if space allowed, such as the incident where his home was ransacked and the safe was blown open, the police even alluding he could have been the culprit – the event providing material for A Scanner Darkly.

The FBI had an interest in him and his second wife, Kleo Apostolides, because of their left-wing views and his latterly reporting academics to them because he believed they were agents of the Warsaw Pact. And, perhaps most incongruous, he expressed the belief that he had also previously lived as a Christian called Thomas, who was persecuted by Romans in the first century AD.

PKD certainly had an eventful life and his works remain popular, as with the 2015 screen adaption of The Man in the High Castle, and other films such as Minority Report (2002). He died of the complications of a stroke aged 53 in February 1982 and was finally laid to rest alongside his twin Jane. It was only a few months before the release of Blade Runner – perhaps it was his time to die.

Philip K. Dick and Malleable Memories

Though not entirely faithful to the book, Total Recall features many of the PKD’s core themes, notably what is real and what is not. If you have lucid memories of a visit to Mars implanted in your mind and, as in the book, are furnished with souvenir artifacts woven into those memories, if the neurochemical framework is the same as having actually been or not been, and the experiences carry the same emotional resonance – what would be discernibly different when recollecting… because neuroscience has shown that memory is fallible.

Famously Loftus and Pickrell’s research in 1995 with the Lost in the Mall experiment showed rich false memories could be implanted in subjects when convincing collaborative material (in their case using narrative booklets) was administered to subjects. This has reverberations not just for the arts, but also for other arenas such as the courtroom.

The film and book have other plot devices that can be viewed alongside psychotic symptomatology. Quaid (Quail in the book), exhibits ‘thought broadcasting’, a key feature of psychosis – whereby others can read his thoughts; PKD often endowed his characters with telepathy and other forms of thought alienation. The film has this played through a transmitter Quaid must remove through his nose; the book gives a less clear explanation with a living psychic entity having been introduced into his brain.

Then there is the psychopathology of dual orientation: Quail is a humble clerk in the book (and a construction worker in the film, better suited to Schwarzenegger’s bulk) and yet displays unparalleled prowess with firearms and fisticuffs – procedural muscle memory which wasn’t wiped. Then there is Sharon Stone as Quaid’s wife Lori, who also believes he’s been to Mars and is an agent – is this a Folie à deux (‘madness for two’), when one psychotic individual is so certain (and usually dominant) that their madness infects another? The film plot has Lori in on the ruse and Quaid’s life is imperiled, whereas in the book she is not part of the deception.

Quaid literally dreams of Mars, with his own death on the surface depicted. We know dreams represent psychological conflicts that haven’t been resolved during the woken hours; Freud described dreams as “postcards from the soul.” So despite his memories of the first trip to Mars being erased, events bubble up from Quaid’s subconscious and he experiences intense emotions of unfinished business. This pulls him into the offices of Rekall, who specialize in implanted memories and offer recollections of perfect vacations, with an added temptation as an option – a chance to take a holiday from you – “The Ego Trip” as marketed. Quaid chooses the character of a secret agent; his very identity, as Hauser, the “agency” has previously erased from him.

The film has the rebel leader Kuato as a (conjoined) twin – though that was not penned by PKD but is one of his motifs, as is his telepathy. And Kuato memorably captures redemption in the film, Hauser (the duplicitous agent) is gone and Quaid is left.

“You are what you do. A man is defined by his actions, not his memory.”

This article was first published on November 26th, 2020, on the original Companion website. The author is a practicing psychiatrist and wishes to remain anonymous.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂