There’s always been a fair amount of contention around Neon Genesis Evangelion. Like anything else that becomes as popular as it did (especially with anime, which attracts its fair share of possessive fans), people can get very particular about what they expect. The most recent iteration of this came in frustration at Netflix when they acquired the streaming rights to the show in 2019. As well as changes to the dubbing actors and a new translation, there was plenty of fury over the absence of the numerous end-credit covers of ‘Fly Me To The Moon’. It feels strange for a show that began in Japan 25 years ago to still stoke this feverish reaction.

This was all minor compared to the show’s historic finale. Received with confusion and then vitriol upon its release, creator Hideaki Anno infamously received death threats, images of which supposedly made their way into his eventual feature-length reworking of the ending, Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (1997). The two-part television finale (episodes 25 and 26) and the film are often presented as an either-or choice. Those who prefer the original praise its seemingly more empathetic presentation. The film often wins favor because of its comparatively higher budget thrills and bewildering aggression. Rather than being a binary choice between two drastically different conclusions, both endings are far more alike than their differences let on.

First, some context. Neon Genesis Evangelion was created by Hideaki Anno, an animator who studied under Hayao Miyazaki of Studio Ghibli (his work includes the utterly immense God Warrior sequence in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, 1984). Post-Ghibli, Anno’s career saw him serve as an animator on Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise (1987), as director on the series Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (1990-1991), and his wild, underrated, and highly emotional mecha OVA (original video animation) Gunbuster: Aim for the Top! (1988-1989). Evangelion might be Anno’s most recognizable work – and also his most personal.

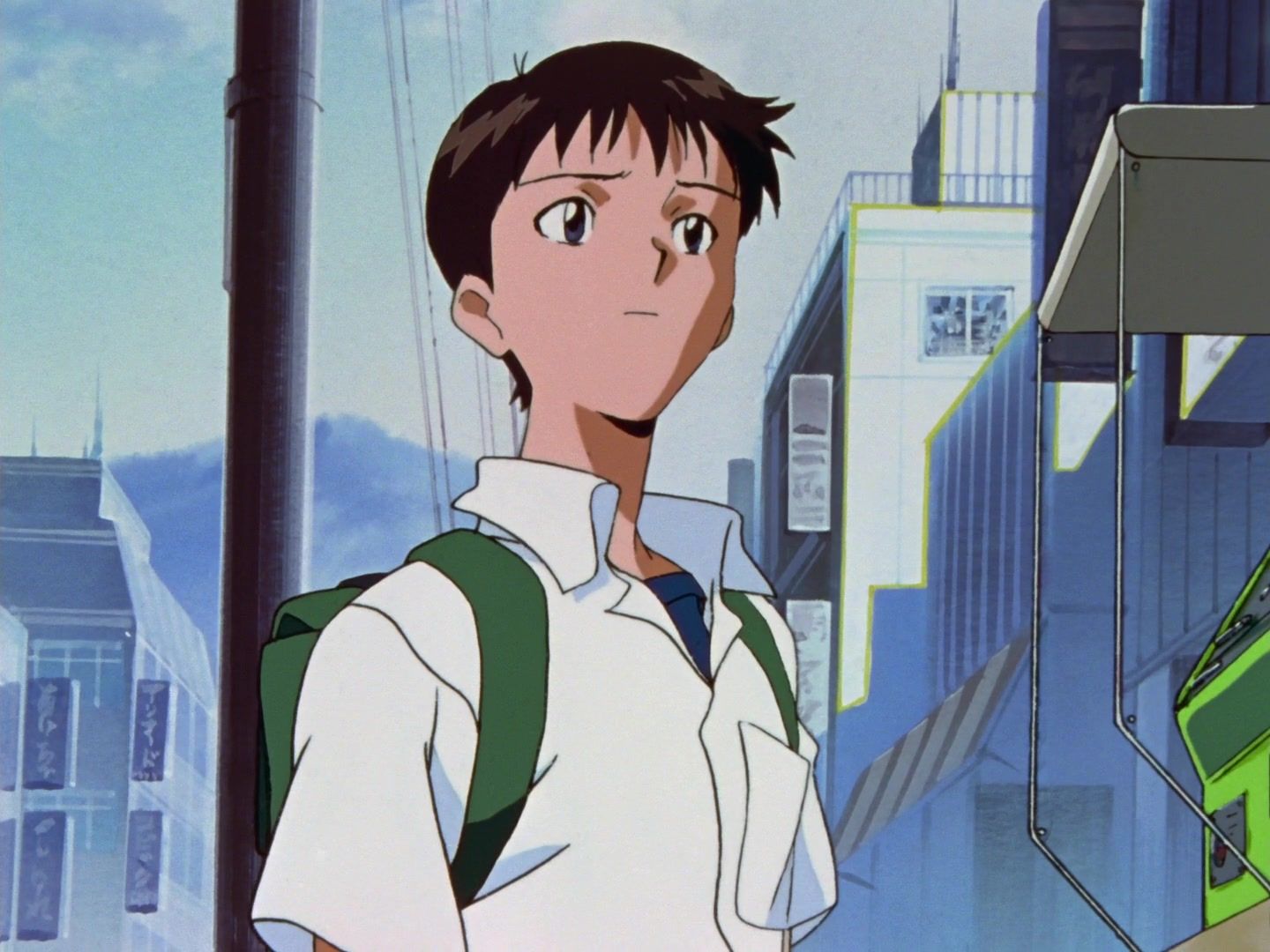

Broadcast on Japanese television from 1995 to 1996 and then followed up with a few movies, Neon Genesis Evangelion centers around troubled teenage boy Shinji Ikari. He is recruited by his absentee father in order to pilot a giant robot (that’s not really a robot) called an Eva, to fight the monstrous enemies called Angels that are attacking the futuristic city of Tokyo-3. Shinji loathes his father and fears fighting, resulting in a series-length identity crisis for the ages.

The show eases into this intensive emotional arc – beginning Misato and Shinji’s relationship as that of a goofy, bickering odd couple. Misato’s volatility comes off as comical at first. Still, as with the other characters, her actions are shown to be rooted in a trauma similar to Shinji’s, and her carefree wildness proves to be a facade for deep insecurity. Their time together is littered with bizarre humor that sometimes feels like it’s reaching for the bottom of the barrel but is charming nonetheless – and also serves to draw a connection with the pop culture that it is deconstructing.

The Genesis of Neon Genesis Evangelion

Throughout the series, Shinji fraternizes and clashes with a few other pilots – the taciturn and mysterious Rei Ayanami, and the brash and confident Asuka Langley Soryu, both of whom have plenty of neuroses of their own. Despite settling into a sort of monster-of-the-week rhythm for its first half, even the early episodes hint at Shinji’s immense inner struggle. Each episode seemingly brings Shinji closer to understanding, then sets him back again. For its final third, the series becomes increasingly abrasive and upsetting, diving deep into the neuroses of Shinji as well as Asuka and Rei during (often involuntary) metaphysical journeys of introspection.

None of this is to say that giant robot shows weren’t thoughtful before Evangelion came along. The pioneer of what is now referred to as the ‘real robot’ genre of anime, Mobile Suit Gundam (1979-1980), was laden with complex anti-war thematics and similarly starred a pilot, Amuro Ray, who wanted nothing to do with big robots. Neon Genesis Evangelion is often held up as a grand deconstruction but – especially in its visuals – it delights in the tropes of the genre, with spectacular fights between the titan Evas and various eldritch horrors of the Angels. It’s hardly the first to put the inner lives and emotions of the pilots at the forefront – after all, this is how Gundam made its name.

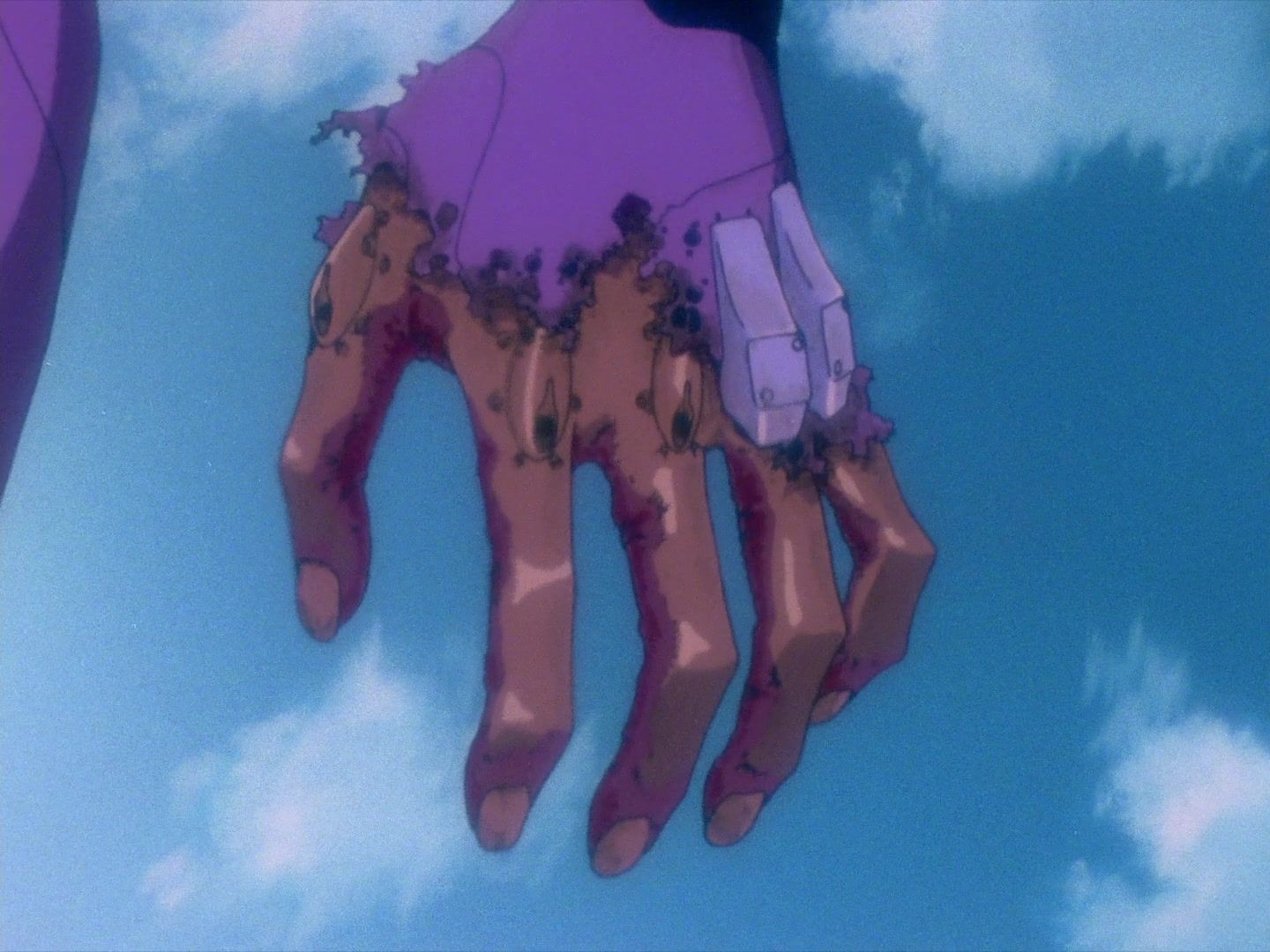

Where Evangelion stands apart is its turn toward abstraction and impressionistic experience over realist detail. A lot remains vague until the very end of the show. It’s also far more grotesque – starting with the Evangelion themselves, which are more symbiotic than robotic. Rather disturbingly, they bleed. Worse still, they’re psychically linked to their pilots and the giant machine’s pain and physical injury are shared with the pilot. All is done so to increase the immediate trauma of piloting one of these things and any thrill is often short-lived.

The world of Evangelion is just as fragile as the psyches of its characters, constantly under threat of total collapse. The main city it takes place in, Tokyo-3 (the last two were destroyed), is one of the last fortresses for humanity following a cataclysm known as Second Impact. Again, this may all sound like familiar ground for anyone who has watched a mecha anime (or even just Gundam), but its formal construction immediately differentiates it. Anno and co. pack the show to the brim with Judeo-Christian and downright Freudian imagery, packed alongside references to Jungian archetypes (particularly that of the anima and the animus) and Kierkegaard. As well as the interior lives of its characters, Evangelion also engages with the nuts and bolts of bureaucracy, espionage, and the secret organizations shaping the future of humanity, in the incredibly complex mythology that can only be managed by multiple Wiki pages.

Existential Crisis in Episodes 25 and 26

Upon the first release of the show’s US DVD boxset, writer Mike Crandol said of Evangelion’s appeal for Anime News Network: “It can be enjoyed at face value as an expertly realized sci-fi action-adventure, but it is also a bleak satire of the genre, a coming-of-age parable, and a treatise on confronting loneliness and uncertainty in the adult world.” Those more conventional elements of Evangelion begin to break apart as the show goes on and Anno becomes more intensely interested in psychoanalysis, focusing more and more on Shinji’s depression.

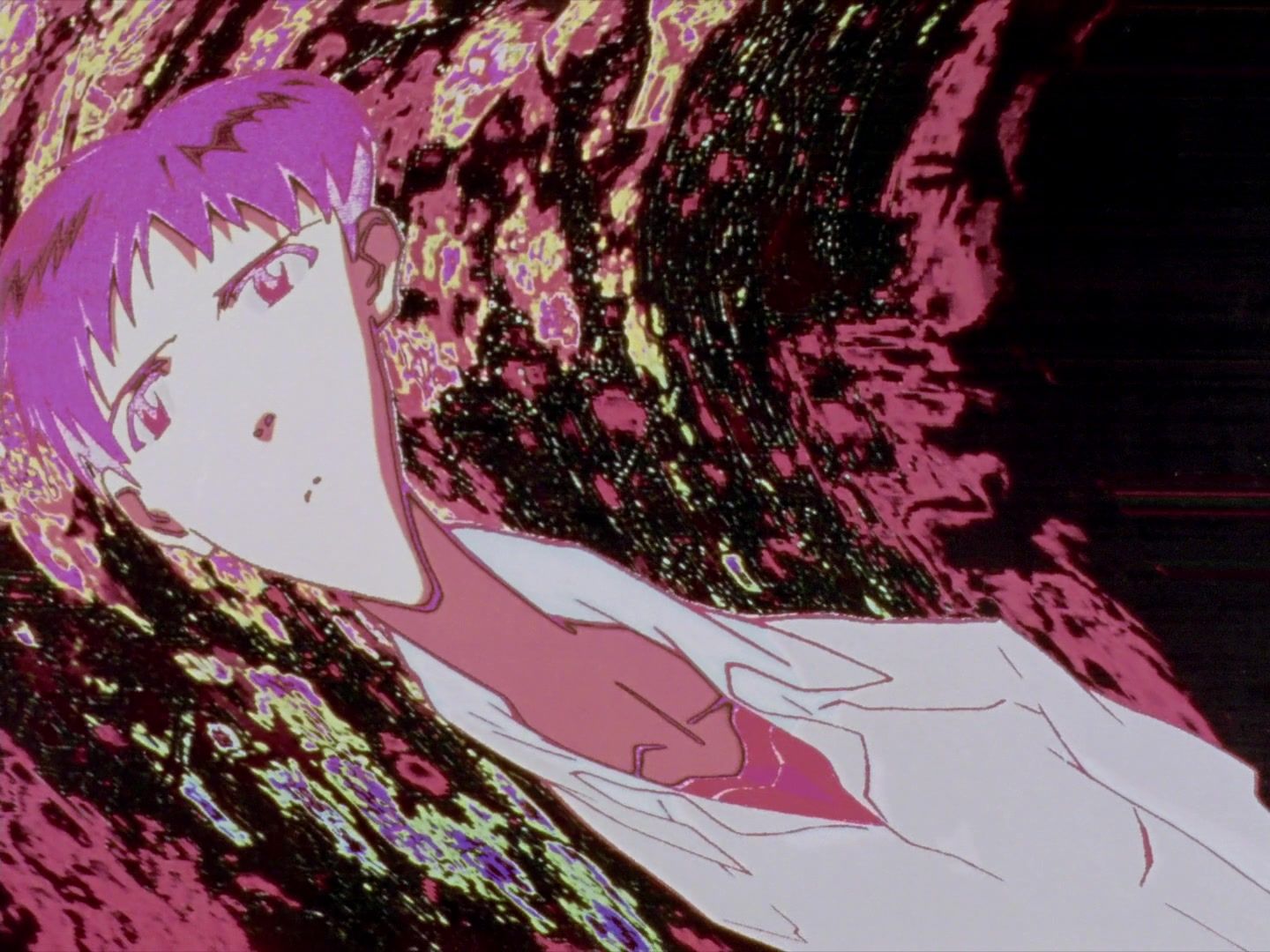

As the end of the show approached, it was behind schedule and out of money, and so the now infamous finale threw out action entirely in favor of a metaphysical group therapy session. The 25th episode, ‘A World That’s Ending’ (S1, Ep25), is the first of a two-part finale in which Anno rebuilds the show into painful, fragmented psychoanalysis, threaded together by reused and altered cel animation from earlier in the series as well as new abstract, trippy animation that embodies Shinji’s confused psyche.

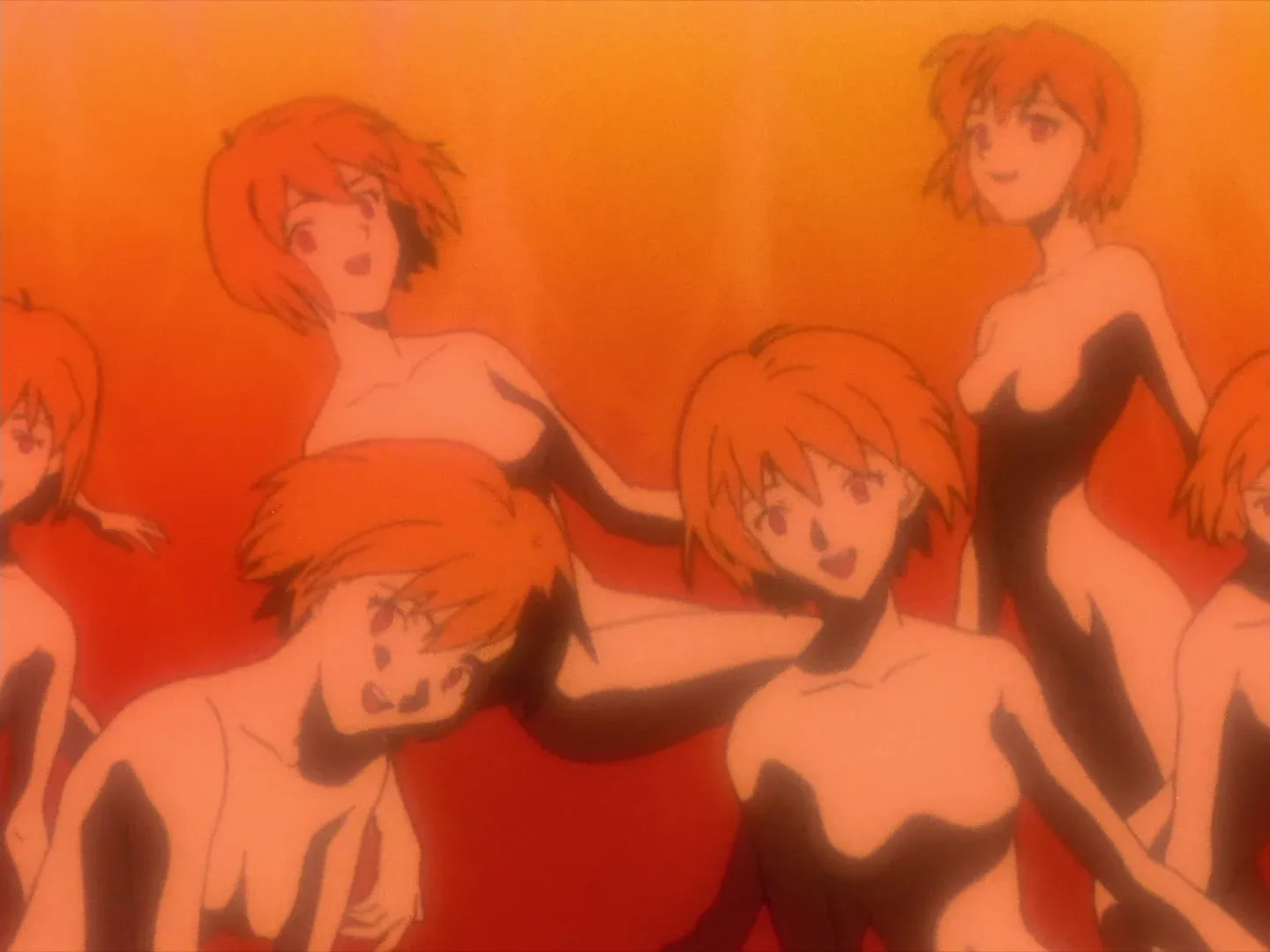

The young Eva pilot’s self-hatred has become so great that he has essentially wished himself into oblivion, aided by the culmination of his father’s ultimate plan for ‘Human Instrumentality’. The idea behind the project is to solve what he perceives as the inherent, inescapable flaw of mankind – that we’re alone from the day we’re born. ‘Instrumentality’ is an escape from loneliness through a return to a primordial state, all people and forms and minds melded together in one big orange soup. To match this deconstruction of the show’s very nature, the animation cels are broken apart and taped back together (during one scene with Misato at least).

The finale is this way partly because Anno was still figuring out what the show meant – it was an extension of himself, and his own struggle with depression. As he became increasingly interested in psychoanalysis, the show began to reflect that interest and the characters all begin to recognize the flaws that drove their actions. Simultaneously they become mouthpieces for Anno to explore his own self-worth.

They still feel like individuals though. Shinji is the only one who (purposefully) feels like a cipher, a person who is only able to find solace when doing as others tell him, and when he is praised for it. The finale is about him claiming an identity for himself. That journey isn’t easy – Shinji’s psyche is revealed like an open wound as Anno cuts right to the core of his fear in two episodes that still feel raw, painful, and candid in a way that few TV series as popular as this had before or since. The episodes explore these ideas purely through sensation and the inner space of the characters’ minds rather than their physical reality, and their interactions with people (or giant eldritch monsters). ‘Human Instrumentality’ occurs in a strange, ethereal plane, we are only privy to glimpses of its physical effects on the world (those frames would later be contextualized in The End of Evangelion).

The pure strangeness and unexpected tangent of those final two episodes weren’t entirely well-received. When the final two episodes aired, Anno infamously got death threats because viewers were so put off by the shift towards the patchwork of voiceover psychoanalysis and reused images from the show, as well as more expressive, rough, and abstract pencil animation. In an interview with the Japanese anime magazine Newtype, Anno said of the finale: “Episodes 25 and 26 as broadcast on TV accurately reflect my mood at the time. I am very satisfied. I regret nothing.” The episode is surprisingly joyous in its emotional breakthrough, and despite some vitriol from a group of loudmouthed fans, those episodes are beloved for their powerful emotional catharsis. What saves the world of Evangelion isn’t a giant final battle, it’s simply the young boy deciding that “maybe I can learn to like myself… it’s okay for me to be here.”

The End of Evangelion

Later, with renewed funding, Anno remade the series finale of Neon Genesis Evangelion as the movie Neon Genesis Evangelion: Death & Rebirth (1997). The first half essentially recapped the show, and the second half added a new ending, this time showing the events of the finale as they occurred in the physical world. This second half would eventually become the first third of Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion, a complete alternative ending to the series in movie form, also released in 1997. Fans of the show were clamoring for a ‘real’ ending, and Anno sure gave it to them. The End of Evangelion is uncompromising in its brutality and misery, putting several exclamation points onto what he was trying to say with the finale. The End of Evangelion, for its first half at least, could be said to be more representative of the sci-fi action-adventure that Crandol spoke of. Still, it’s also more aggressive (and explicit) in its bleakness, violence, and confrontation of loneliness than the show ever was.

Where the show’s final two episodes exist entirely on an abstract and metaphysical plane, The End of Evangelion is about the horrifying physical reality of Gendo’s plan and Shinji’s destructive wish for a world without pain, as all of humanity literally melts into an orange soup. After all that demand, Anno served up the answers that braying fans craved in the most grotesque manner possible. The End of Evangelion is practically anti-fan service, a trip through the worst-case scenario for every beloved character, while the ‘hero’ Shinji remains despondent in the wake of the traumatic act of having killed Kaworu, the person who he thought would be his salvation from loneliness.

It might also be the sharpest and harshest depiction of Shinji yet. Up until perhaps the final 10 minutes of the film, the only moments where he is capable of being anything more than passive, is when he’s acting destructively, to himself and everyone around him. Neon Genesis Evangelion as a series has caught flak (probably fairly) for its indulgence in the same puerile attitudes towards women that it critiques. Though Misato, Asuka, Ritsuko, and Rei are all deeply flawed individuals with complex inner lives that receive as much focus as Shinji does – they’re still objectified. The End of Evangelion itself seems to reckon with this, having that manifest as part of Shinji’s character, as his moments of desperation and confusion turn him into a violent and even perverse misogynist. When Asuka refuses to help him, he hurts her.

Shinji’s own awfulness couldn’t be more apparent to him, the acts he commits are all part of some twisted self-flagellation, an attempt to drive everyone he cares about away from him as he feels he doesn’t deserve affection. It’s the clearest version of the show’s ongoing critique of ‘otaku’ culture and toxic masculinity in ways that are shocking to see from the hero of a story, giving in to predatory and destructive acts as he begs for someone to save him from despair. Anno also uses The End of Evangelion to interrogate art as a means of connection, in one stunning moment removing the barrier between film and audience as it briefly switches into live-action, even flashing letters from fans on screen. That thorny acknowledgment of both the reasoning behind and Shinji’s culpability in such actions is a depiction of depression that still feels rare, in animation or otherwise. (Perhaps Bojack Horseman could be considered a successor in animation popular in the West – but that doesn’t have giant robots).

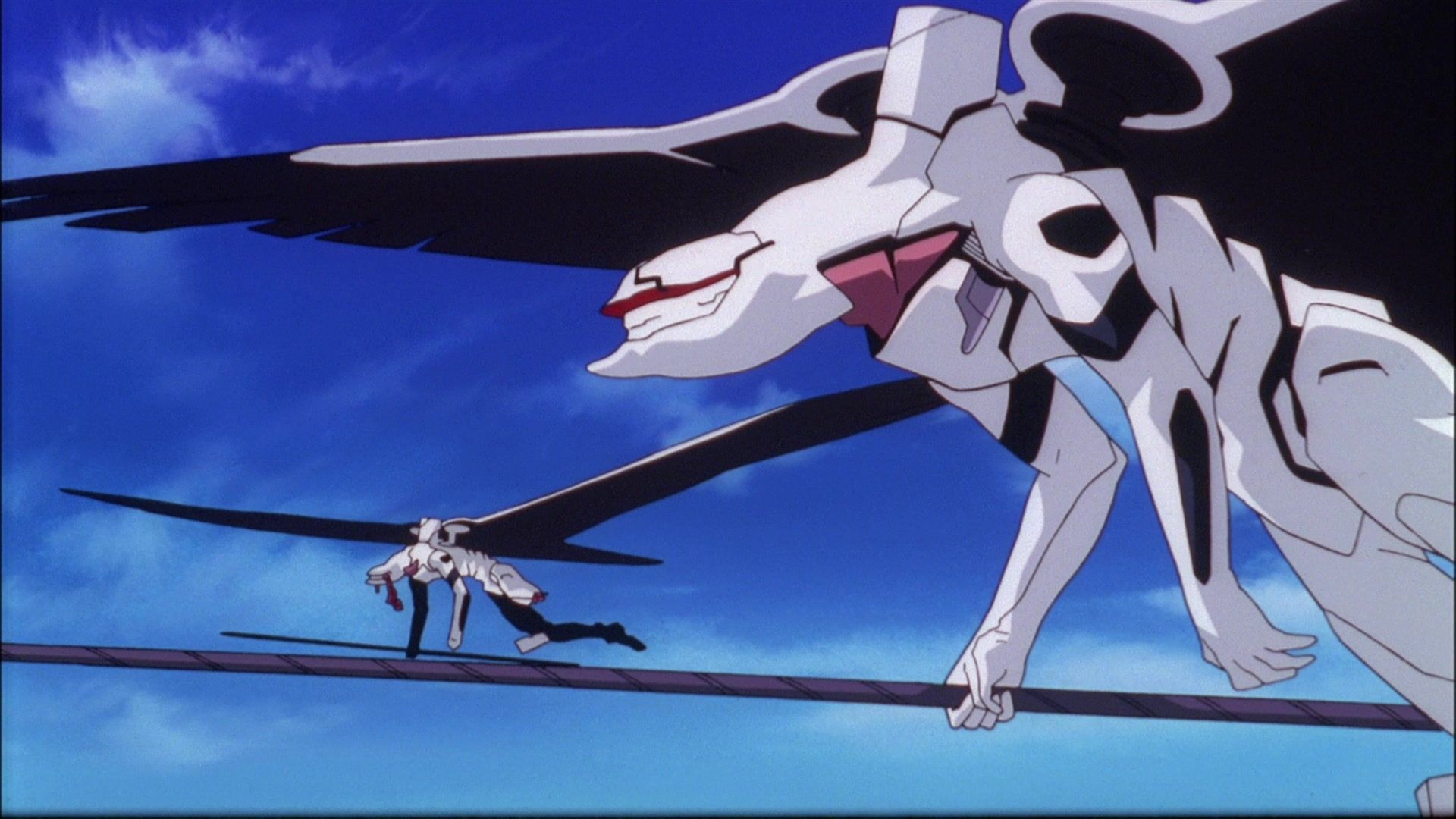

Both the Evangelion finale and End of Evangelion are very simple at their core – they’re about the realization that depression isn’t cleanly fixed, but progress has to come with the willingness to make that progress. In contrast, the dysfunctional Shinji either retreats or seeks out approval from others. Evangelion is a story about understanding and facing trauma again and again, and the self-understanding that is needed to heal. The End of Evangelion is perhaps the most grueling example of that, with moments like Asuka’s final stand against the grotesque, autonomous Eva series, even crushing what seem like rousing victories. The set piece itself is a great example of how the film goes about working through its characters, tracking the same emotional arc for Asuka (the realization that her mother loved her, and the regaining of her self-confidence) through her very movements. It’s a stunning sequence that expertly merges action with character analysis, with Asuka’s state of mind embodied in her newfound ferociousness and grace in piloting her Eva. That she still fails is the final punishment in a long series of them, the film asking the viewer to shoulder the burden just as the characters have.

Both versions of its finale reach a similar conclusion via routes that are superficially different, but thematically the same. In both the film and the series finale Shinji finally finds himself in true isolation, told by an otherworldly voice (later revealed to be that of Rei, who has ascended to godhood as Lilith), that “this is the outcome you wished for.” “For destruction, a world where no one is saved… a return to nothingness. You wished for a closed-off world that would be comfortable for you and only you.” The same is said to him of the ending world in The End of Evangelion, that the only kind of Earth where Shinji would be able to escape from his problems rather than confront them, is one where people no longer existed. But this is running away, something Shinji has been doing since before the series began (“I mustn’t run away” is a persistent mantra when he’s under stress), and a path that has always brought him hurt.

The series finale uses its rough and almost alien animation to embody each character's confusion and mind space. The screen goes completely blank at one point to represent “a world of freedom”, where no rules, and therefore nothing, exists. The End of Evangelion uses similar abstraction, but with more complete and detailed images, and destabilizes its formal content even further by cutting to live-action, and then breaking the fourth wall – displaying an image of the audience watching the film at its first screenings.

As similar themes persist between the two films, so does imagery. The pain of separation between people is emphasized by white spaces in both the series finale and the movie. Shinji’s desperate clinginess and infatuation with all of the women in his life – Misato, Asuka, and Rei – becomes part of that imagery in both. In The End of Evangelion, he is isolated in a train carriage, avoiding their eye out of shame, in the finale he covers his eyes and ears as their ghostly figures surround him. That repetition is key to Neon Genesis Evangelion. In his announcement that he would be returning to remake Evangelion – a project which culminated in 2021 with Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time – Anno said:

“Eva is a story that repeats. It is a story where the main character witnesses many horrors with his own eyes, but still tries to stand up again. It is a story of will; a story of moving forward, if only just a little. It is a story of fear, where someone who must face indefinite solitude fears reaching out to others, but still wants to try.”

The character motivations and insecurities laid bare by the onset of ‘Human Instrumentality’ are still the same. Misato’s uncertainty about her relationship with Kaji and confusion about how she wants to be seen persists across both. Asuka’s insecurities, interestingly, are resolved through action – which perhaps makes more sense for the story, as Asuka’s self-confidence and abandonment issues have always been inextricably tied to the Evangelions, more so than Shinji. Because of that abandonment by her mother, she needs to be the best – and for a few minutes, she is. Her realization that the soul of her mother resides in her Eva (yes, really) is what finally breaks the spiral that started midway through the Evangelion TV series. Because of that use of action in its character work, that final, abstract journey of ‘Instrumentality’ plays out with a more singular focus in The End of Evangelion – it’s all about Shinji’s neuroses.

A Deeper Dive into Shinji’s Self-Hatred

The fate of the entire world now hinges on the fragile mind of a boy who has never known any certainty or security except for the fact that he wants to escape, whether that’s into the comfort of other people or into isolation. That second impulse begins to lead and becomes destructive and hateful. The world ends when Shinji lashes out at Asuka in anger, strangling her when she refuses to help him. It’s a shock because Shinji has remained a passive figure throughout the series and up to this point, you don’t expect him to be capable of it.

The original series never explored that anger. Shinji’s self-hatred turns into cruelty so as to ruin relationships with the only friends he has and extinguish the love he feels he doesn’t deserve. That self-immolation manifests itself in the very imagery of The End of Evangelion, especially in its second half. Bodies are destroyed and devoured, and the planet itself is eventually consumed and ravaged in a moment triggered by Shinji’s emotional state, with imagery ripped straight from the Book of Revelations. Where the series finale left such imagery behind for something more subdued and abstract, The End of Evangelion returns to the series’ blood-soaked mix of Biblical imagery and eldritch horror, building off various foreshadowing that the show’s finale swept aside.

It’s tempting to view The End of Evangelion as the more complete ending, especially with the knowledge of the issues surrounding the production of the original. But the film capitalizes on episodes 24 and 25’s lengthy breakdown of its characters’ insecurities, allowing more shorthand in the film’s final chapter.

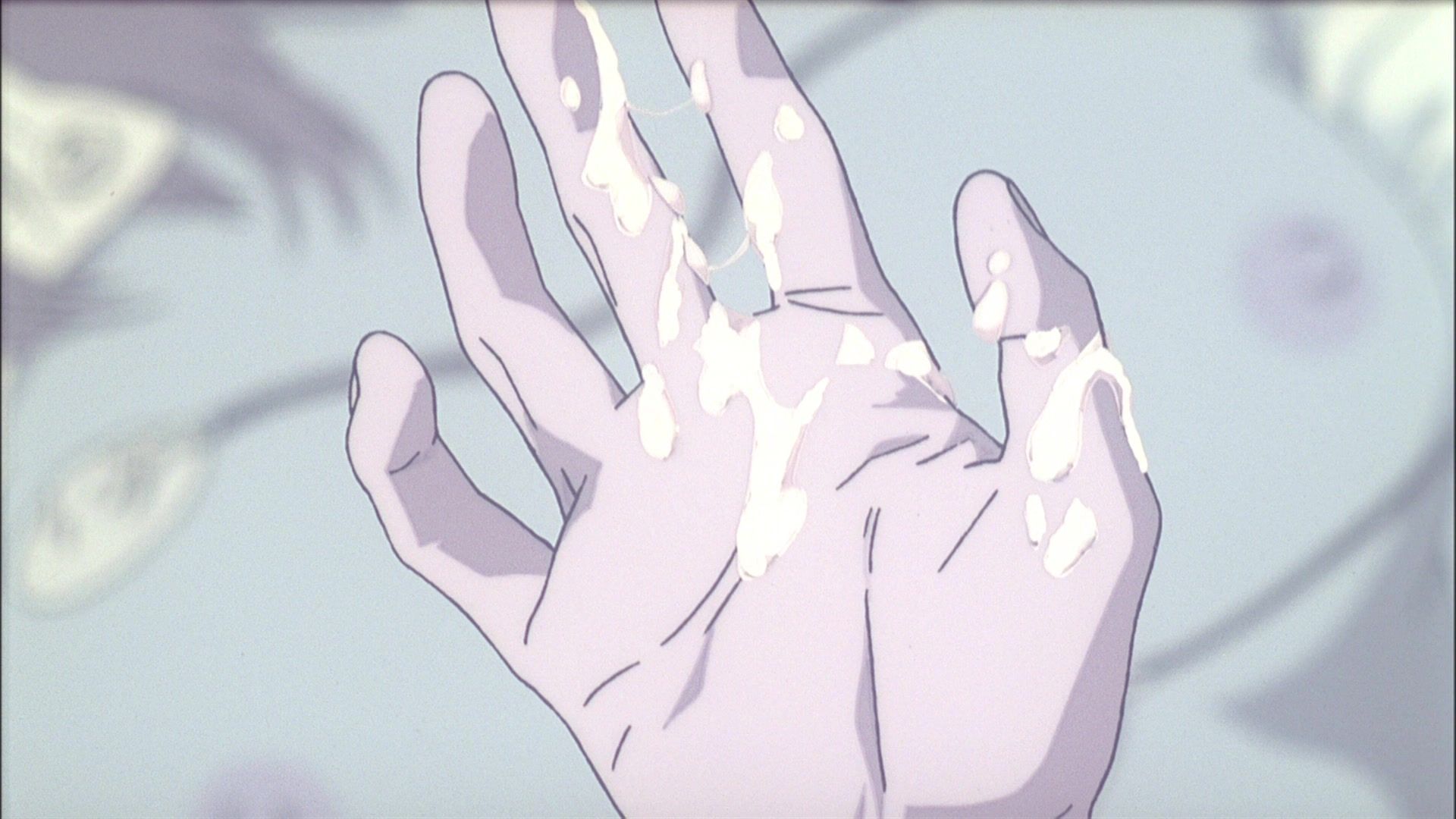

But then they go beyond his own reality, into live-action. The possibilities for Shinji’s life expand beyond such wastefulness and despair, for him to find a connection with someone. It’s reinforced by dialogue with Kaworu and Rei, with ghostly messages from his mother Yui (whose soul also resides within his Eva), and is finalized in the final action of the film – Asuka finally reaching out her hand to him. It’s not to say that Shinji’s ills will be defeated by the comfort of a girlfriend – after all, he had to literally form his own body again and reject the manufactured paradise of Instrumentality through sheer force of will – but that outstretched hand is everything, a final confirmation that there’s hope.

Perhaps the main difference is that The End of Evangelion embodies its themes in its action, whereas the series finale bends the form itself to question the very nature of being. These dual endings aren’t incompatible. In fact, they complement each other, as the final episodes turn the series’ subtext into text, breaking each character down and building them back up with renewed self-understanding. For all of the superficial differences, it all leads to the same breakthrough for Shinji. That moment of hope may be best summarized in ghostly parting words from his (long-dead) mother Yui:

“Anywhere can be paradise as long as you have the will to live. After all, you are alive, so you will always have the chance to be happy. As long as the Sun, the Moon, and the Earth exist, everything will be alright.”

This article was first published in two parts on November 16th, 2020, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂