You might remember the scene.

On the ravages of a storm-covered battleground, Thanos the Mad Titan, determined to use the Infinity Gauntlet to wipe out the entire universe, stands triumphant having cast off Captains America and Marvel, Thor, and Iron Man, about to click his fingers and complete his work. “I am… inevitable,” he promises, before realizing Tony Stark has pilfered away the Infinity Stones from his gauntlet, only to channel the same power within him. “And I… am Iron Man” Tony declares as he clicks his fingers, Thanos and his forces crumble to dust, and Iron Man gives his life to save the universe.

The final act of Avengers: Endgame (2019) is hard to forget given how well-earned the sacrifice of Robert Downey. Jr’s Tony Stark was. The film served as the culmination of a decade of storytelling that changed the face of mainstream cinema. Back in 2008, when Jon Favreau’s Iron Man introduced Tony Stark to a world largely unaware of the character outside of the relative niche comic book arena, few audiences could have imagined he would serve as the vanguard of the first successful cinematic universe. Iron Man lacked the cultural imprint of Spider-Man or the global traction of the Hulk, Marvel creations who had long evolved beyond their roots on the page. He was the unlikeliest of characters to bear a transformational development in franchise filmmaking.

It cannot be overstated how crucial Downey Jr. was to this cultural moment. A transformed character himself, having survived the career-destroying scandal of drug abuse and imprisonment after initial Hollywood success, Iron Man (2008) did not just cement a career comeback but turned him into a global mega-star thanks to his charismatic portrayal. This led in no small part to the film, and the moment, that turned a successful series of connected films into a driver of the zeitgeist: 2012’s The Avengers, Joss Whedon’s bravura union of Marvel’s initial assortment of superheroes – Iron Man, Thor, Captain America, Hawkeye, Black Widow, and the Hulk. Whedon’s film changed the game, fully establishing what we understand as the Marvel Cinematic Universe for the first time.

At the root of this universe were Tony Stark and Chris Evans’ Steve Rogers, the Second World War hero thawed out in the modern day; a noble, earnest man out of time serving as a deliberate counterpoint to Tony’s slick, fast-talking billionaire. Their initial friendship, and ultimately both the geopolitical and highly personal factors which drive them apart, existed as the backbone to the first three ‘Phases’ of the MCU, a name given to delineate the chapters in a broader story that began to form around the key touchstones of the latticework of MCU films. The Avengers (2012) was the first, Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015) the second, and Avengers: Infinity War (2018) the third. The confluence of characters and storylines in these films informed what came before and what was to happen next.

Introduction: The First Few Episodes

In this, the Marvel Cinematic Universe very quickly differed from blockbuster franchises of old, especially that of the comic-book cinema it followed. 1978’s Superman, from Richard Donner, could be seen as the bedrock of what comic-book cinema was before the MCU; a big-budget adaptation of pulp material that took seriously Clark Kent and the tragedy of him being the last son of Krypton. “You’ll believe a man can fly” went the tagline, and it was true. Audiences did. They wanted more. And the 1980s witnessed the true birth of the superhero sequel, buoyed by the rampant success of George Lucas’ Star Wars and the arrival of popular American blockbuster entertainment, which saw three Superman follow-up films, mostly made up of diminishing returns.

Sequels had existed for decades in Hollywood, stretching back as far as the 1910s and the birth of silent film, but not until the 1980s did cinema truly cement the sequel as a form boasting a continuing story, whereby audiences would revisit characters they enjoyed and witness the development of their lives. Star Wars established the concept of the movie ‘trilogy’ which for many years became prevalent in blockbuster franchises – take Indiana Jones, The Lord of the Rings, or The Matrix as examples. Many of these later adopted a fourth or fifth movie, or the properties expanded as they transformed into a franchise, but the initial scope was more limited. Some told a continuing story. Others, such as Indiana Jones, merely placed the character in a new and different scenario.

Hugely successful and popular as many of these film series were, none of them undertook the scope later propagated by the MCU. Comic-book cinema handed the baton from Superman in the 1980s to Batman in the 1990s, after Tim Burton’s wildly successful 1989 darker, Gothic take on a character primarily known to audiences for the enjoyably camp 1960s show. Though the Batman series varied in quality, it provided enough of a barometer for success to make the adaptation of Marvel properties, as the 2000s beckoned, a going concern. The Spider-Man trilogy from Sam Raimi became hugely popular, as did what could be argued as the first significant ongoing comic-book franchise – the Bryan Singer-instigated X-Men series, which spanned nearly 20 years and almost ten films.

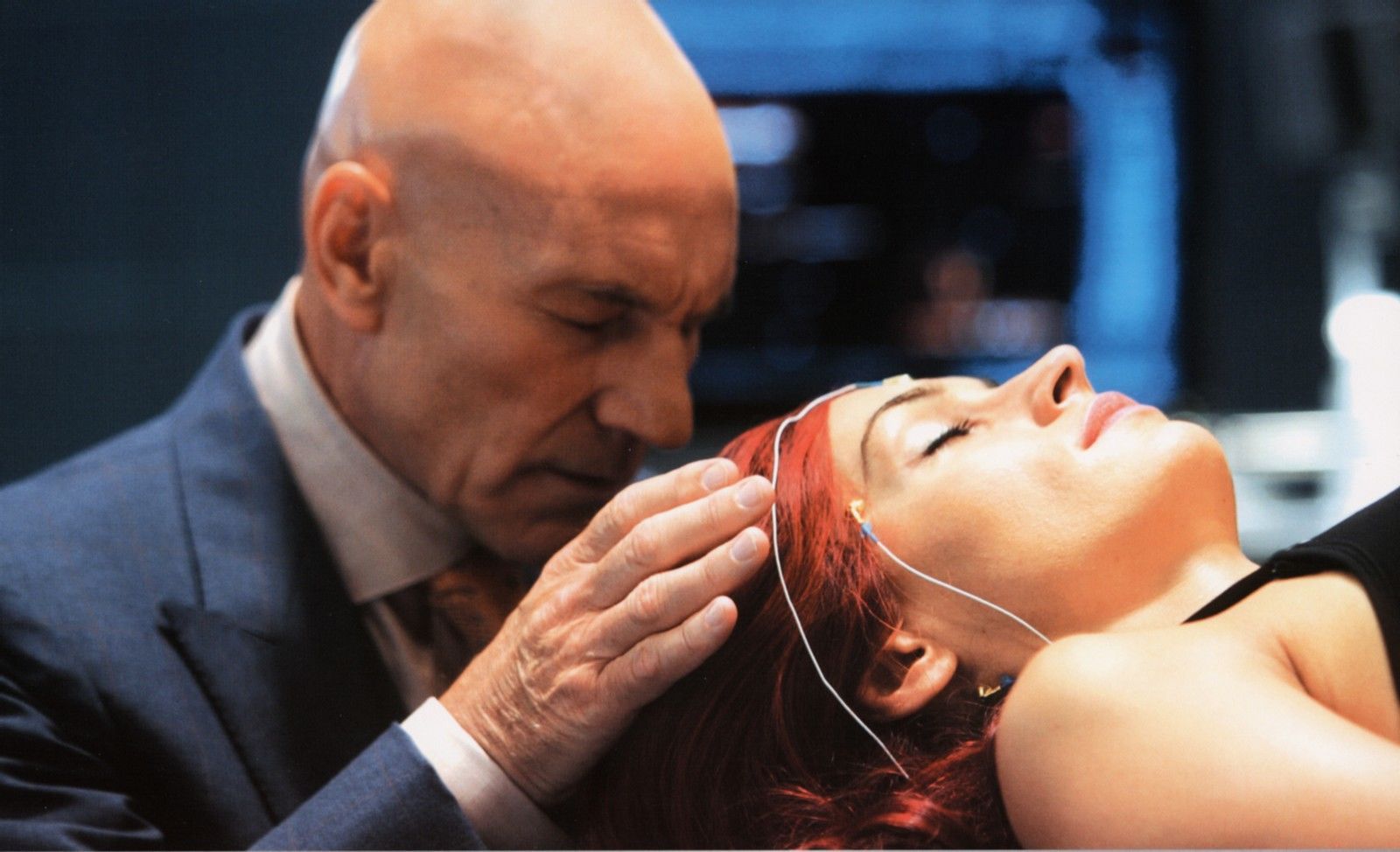

What none of these series or franchises did, however, was provide a joined-up narrative with consistency. Actors were often recast between films. Storylines were adapted and then sometimes dropped. Directors were hired and fired, many of them bringing new stylistic approaches to the films, characters, and storylines that had already been established. For example, Brett Ratner took the decision in X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) to kill off Patrick Stewart’s Professor Charles Xavier yet leave a hint that his consciousness existed in a clone body. When Stewart returned to the role almost a decade later in X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014), no mention was made of the mechanism for his resurrection on screen, despite the film taking place within the same continuity. These narrative incongruities were common in this era of world-building.

This changed significantly with the arrival of the First Phase of the MCU. Iron Man (2008) introduced a rarely utilized narrative idea into the cinematic mainstream – the post-credits sequence, which Marvel swiftly employed as a mechanism both to provide a final comic beat or, most frequently, tease a development in the broader universe to come. Iron Man introduces Samuel L. Jackson’s Nick Fury, director of S.H.I.E.L.D., who expressly mentions the ‘Avengers’, thereby sowing the seeds for a film Marvel already intended to make. This would not be the third film in a trilogy. By the arrival of The Avengers (2012), the MCU was already made up of five movies featuring the heroes who came together in that film, many of whose storylines in even minor ways overlapped.

Marvel’s approach to the narrative was, from 2008 onwards, designed to interconnect and very clearly worked as part of a broader master plan. It very quickly became clear the architect of such design was Kevin Feige, himself a producer on the X-Men saga, who adopted the lessons learned on that long-running series as he worked, alongside key founding fathers such as Favreau, Whedon, and later Joe and Anthony Russo, who would direct both Captain America sequels and the two-part Avengers conclusion, to fashion this series into what we would understand as a Cinematic Universe; not just a series of sequels, or a collection of trilogies, but a unified, interlaced whole that built on what came before.

Complication: The Series Get Into It

Through this approach, Marvel introduced two elements into cinematic storytelling that had heretofore not existed in this manner. Firstly, the structure of long-form television ported into the big screen realm and, secondly, a specific narrative form that existed within such television – a sense of internal mythology or what has otherwise been termed as a ‘Mytharc’.

If the most successful properties within blockbuster filmmaking had, a few outliers such as the James Bond franchise aside, been characterized by profitable trilogies or sometimes ‘quadrilogies’, then long-form television had for years been constructed on the concept of the ‘season’. Beginning in the Autumn and concluding in the early Summer of the following year, traditional network television from the 1980s into the 2000s (and in some cases to this day) followed a seasonal pattern designed to keep audiences watching over a collection of episodes that ran anywhere between 20 to 26 hours each year. Within that format would, depending on the show, exist ‘arcs’ or two or three-part stories that would forward major character or narrative points in the series, and would often be flanked by ‘stand-alone’ stories that played with the conceptual setup of the series.

Outside of the myriad number of procedural cop or hospital TV dramas that followed such a format, so-called ‘genre’ television (roughly designated as science-fiction, fantasy, or offbeat series) would frequently subscribe to such a format. The X-Files, perhaps the most popular genre series of the 1990s, utilized such a format, combining the procedural nature of standalone storytelling with what became known as ‘mythology episodes’ peppered throughout each season; stories that would advance not just the personal lives of protagonist Agents Mulder and Scully but inch forward the so-called ‘Mytharc’ at the heart of the series, and advance the broader world-building of the show while posing more questions and resolving certain mysteries.

It was via The X-Files that the term ‘Mytharc’ was first coined in the mid-1990s. The origin of the term remains somewhat nebulous, though it appears to have been propagated on message board discussions by fans who sought to unify terms that had existed for much longer, that of the ‘Mythos’ and the ‘Arc’. The Mythos in storytelling pulls together the idea of a mythic structure underpinning the world-building of a series (with a good example being the world of horror author H. P. Lovecraft) and the presence of an ‘arc’; the ongoing narrative construction of a journey undergone by a particular character to reach a specific conclusion. Due to the nature of long-form genre television, it was in series such as The X-Files or Lost, or Game of Thrones that this combination of world-building and narrative mythology could bear fruit over hundreds of episodes and multiple seasons.

Frank Spotnitz, executive producer of The X-Files, told me that he felt the term Mytharc was too grand for merely a television series:

“I guess it suggests that there is something archetypal about that storyline. I’m not sure that there is, but I guess that’s better left for others to judge. I suppose it refers not just to the defined plot and characters that are in the alien conspiracy storyline but all of the themes and narrative possibilities it suggests. In the case of The X-Files, every time we answered a question we were sure to ask several more. The longer the series went on, the more questions there were for which the audience expected an answer.”

Such examples of the ‘Mytharc’ often correlated with the work of Joseph Campbell, who in the late 1940s famously wrote The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) and developed the idea of the ‘Hero’s Journey’; the natural path of a hero born from studying the classical comparative mythologies and archetypes of dozens of cultures across history, which followed similar tentpoles in each scenario. The hero would journey outward from a place, seek a ‘treasure’, be guided by a mentor, face a reckoning with a father figure, and finally return to the beginning changed within while influencing the world without. Lucas most famously employed this structure in the Star Wars saga, across two different trilogies, but examples of this exist in well-known television or literary characters such as Fox Mulder, Jack Shepherd, or Jon Snow.

Much has been written on how Tony Stark’s arc as Iron Man corresponds to the Campbellian ‘Hero’s Journey’, how he undertakes from his first movie all the way through to Avengers: Endgame a mythological and spiritual journey outward and inward, before giving his life to save the world. Yet less has been said about how the MCU works to adopt the format of long-form television across the first three Phases of the franchise with a deliberate intention to ape the mythological storytelling approach of numerous of the above examples, and more besides including Babylon 5, elements of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and even less successful shows like Alias and Millennium, or one-hit wonders such as to Odyssey-5 or Alcatraz.

Resolution: The MCU Season Finale

If the first three Phases can be construed as being bookended by Avengers movies that tie together numerous character stories, then they should be examined more closely as examples of the long-form storytelling structure of a television season, and via three distinct structural elements: Introduction, Complication, and Resolution.

In many genre shows, the first six or seven episodes would frame themselves around introducing either the setup of the show (if it was the first season) or the setup of the season itself, and in all three Phases we can see the MCU in such an introductory mode. Phase One presents the initial collection of Avengers, before Phase Two provides Ant-Man and the Guardians of the Galaxy, while Phase Three gives us Doctor Strange, Captain Marvel, and Black Panther, not to mention the arrival of Spider-Man in a new guise within this more expansive universe.

The eighth to the 13th or 14th episodes of a long-form season introduce a complication, as narrative and character arcs deepen, further storylines and mysteries compound, and the world begins to expand around them. The MCU combines complication and introduction at the same time with films such as Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) or Doctor Strange (2016), which pry open new aspects of the broader universe in presenting these new characters, allowing the MCU to expand into sub-genres that the traditional ‘superhero’ film would have struggled to adopt – in these cases science-fiction space adventure and magical surrealism. Phases Two and Three utilize the complication of their overarching mythologies to widen the scope of the universe and the possibilities of storytelling.

In the final stretch of episodes covering the 15th through to the 22nd, the resolution phase works to stitch all these elements together, combining the established character arcs and developing storylines and pushing them toward either a conclusion, if it is the final season, or the conclusion of the seasonal narrative while providing a pathway toward future seasons. Captain America: Civil War (2016) and Thor: Ragnarok (2017) serve as key examples in Phase Three of early resolution storylines that combine complication and play into the key concluding films, equivalent to the season or series finale in television terms, of both Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019), which fuses together everything the MCU has developed over the previous 20 films into a climax the audience has spent quite literally years waiting for.

We can see different examples of these styles in TV series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which each season would provide what became known as the ‘Big Bad’, the ultimate villain of the piece who Buffy and the Scooby Gang would have to battle in the finale. If we are to consider the MCU as equivalent to a ‘season’ of television, the Big Bad is arguably Thanos, who is teased in films such as The Avengers (2012), Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), and Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), before fully emerging in the two-part finale. Moreover, we are reminded of Game of Thrones’ sense of delayed expectation in the confrontation with Thanos that even the characters in-universe, particularly Tony Stark, know is coming years ahead, even if they do not know the specifics of what will happen. In Game of Thrones, both characters and the audience from the very first episode are expecting the return of the mythical White Walkers and/or the invasion of exiled dynastic leader Daenerys Targaryen, both of which only happen in the very final season.

In this context, the mythology of the MCU, and the journeys of Iron Man and Captain America that underpin the development of the first three Phases, can be seen as a told and complete story between Iron Man and Avengers: Endgame. Both characters undergo circular, mythological narratives in different ways. Steve Rogers begins as the lost hero of a bygone age and returns to the point he began with a second chance at life with the love he lost. Tony Stark begins as a genius billionaire inventor riven with hubris who makes serious mistakes, is humbled, and later gives his life to save the world, as much a Judeo-Christian journey as a hero’s narrative by the end. Around each of these arcs, which drive the complex web around the Infinity Stones, Thanos’ ideological plan, and the fate of the Avengers, are multiple sub-genre stand-alone origin and sequel stories for characters within the same universe, even if their own tales do not influence the broader outcome of the Mytharc.

The MCU has not ended with the conclusion of Tony and Steve’s storylines, of course. Quite the opposite. Phase Four, as of publication, is engaged in the introductory phase of an era thus far defined by time travel, the Multiverse, and the arrival of new characters and sub-genres into the patchwork, as we have seen before. We do not yet know the shape of this new ‘season’, or the possible new Mytharc in play, but this was true at the beginning of the MCU as Iron Man, Captain America, and the original unified team arrived. Storylines and sweeping narratives take time to grow and ferment, to complicate and then resolve. But the MCU, in creating the concept of a cinematic universe that numerous franchises—from Star Wars to DC Comics and many more—are looking to replicate, has set a benchmark in terms of audience expectation and satisfaction.

In the wake of Avengers: Endgame, social media was flooded with audience reactions to Iron Man’s sacrifice, or Captain America finally wielding Thor’s hammer Mjolnir, which was incredible to behold. Audiences, after investing for over a decade in these characters and the mythology of this world, were thrilled, agonized, and ultimately rewarded for their dedication. If Marvel can pull that off again in what we can logically term the MCU’s ‘second season’, building on everything we have gone through before, then the reward could be even sweeter the second time around.

This article was first published on September 9th, 2022, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂