When Brett Leonard was 20, as the ‘70s became the 1980s, he left his home in Toledo, Ohio, and headed west. Only unlike most wannabe filmmakers, he didn’t land in Los Angeles. Instead, he found himself almost 350 miles north, in the small student town of Santa Cruz.

For a young guy interested in technology who wanted to make science fiction, it was a good place to be and a great time to be there. Leonard went to parties where he smoked weed with Steve Jobs, meeting and hanging out with many of those who would go on to become Silicon Valley pioneers like Daniel Kottke and Alan Lundell. One day, he went with his friend Jaron Lanier to a 24-hour technical ‘bake-off’ called Cyberthon, where Lanier introduced him to the concept of virtual reality, a term Lanier had coined. Leonard loved it.

Ten years later, Brett Leonard was officially a movie director, with a low-budget slasher about a zombie doctor – 1989’s The Dead Pit – under his belt. Meanwhile, some producers had bought the rights to a Stephen King short story about a man terrorized by a lawnmower that is being telepathically controlled by a Pan-like gardener and was looking for someone to turn it into a film. Leonard immediately knew how it should be done. It needed to be a movie about virtual reality (VR).

As Told By

Brett Leonard (director/co-writer), Michael Limber (visual effects; Angel Studios), and Tony Doublin (miniature photographer).

“Nobody understood what the hell I was talking about,” he laughs now. “I made a 20-minute educational tape [for the producers], me chroma-keyed against all these crazy VR visuals. I wish I could find it because it’s hilarious.”

The moneymen were almost convinced but needed a bit more proof that what Leonard had in his head could actually be replicated on-screen.

“[The company] Pacific Title had a technique called the Gemini process, which took something from digital and put it on film,” he says. “It was literally putting something digital on a high-resolution cathode-ray tube [CRT] screen frame by frame and shooting it with a motion picture camera. This was a digital optical printer essentially.”

No one believed Leonard would be able to create the virtual reality effects in a high enough resolution on his budget, so together with Pacific Title, he created a blind test and pulled young people off the street to see if it would pass muster. “They said, ‘looks like T2 and Total Recall,” says the director. He got his money.

The CGI of Lawnmower Man

Unfortunately, he didn’t get much. Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991) had come out not long before and featured seven minutes of groundbreaking special effects, but cost $120 million. Leonard’s vision of The Lawnmower Man required 27 minutes of FX – he was given $5 million. With the big effects houses out of his price range, Leonard had to think cleverly. He turned instead to engineers and software firms, including, he says, “a company that had been working on Mexican tire commercials.”

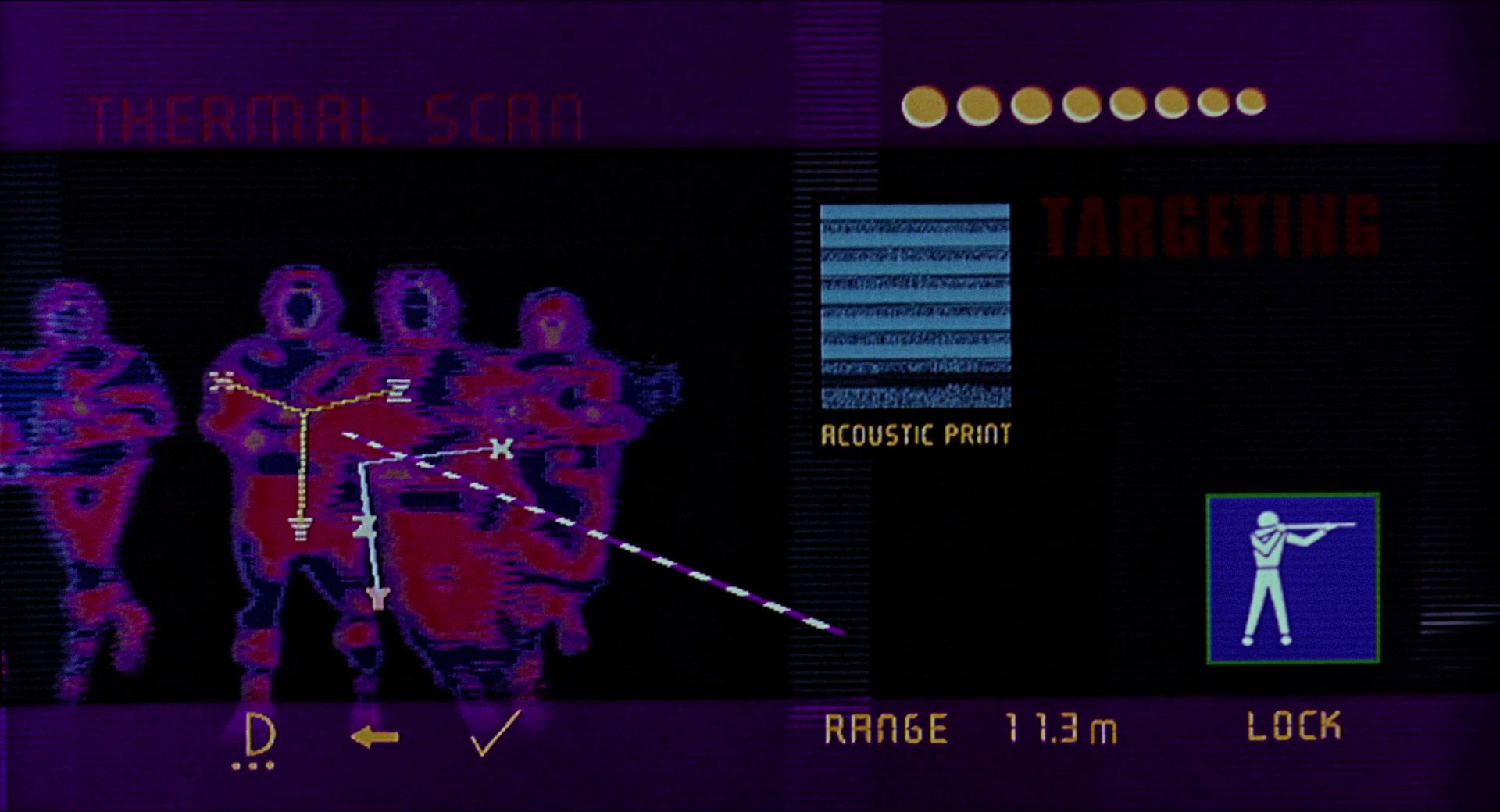

At the time, Angel Studios was a small start-up in San Diego, making TV ads, a few tests for a Star Trek project that never happened, and the odd visualization that was shown at SIGGRAPH, the premier conference for computing innovators. “There were five of us,” says Michael Limber, who worked there. “I think my title was director of computer animation, but it wasn’t like a lot of people to direct.” Limber, along with engineer Brad Hunt and colleague Jill Hunt was introduced to Leonard and agreed to produce eight minutes of effects in eight months, focusing on the VR stuff. Another company called Xaos (pronounced Chaos) was hired to do most of the 2D animation.

Rosco the Chimp is killed by VSI security in the opening sequence of The Lawnmower Man (1992). | New Line Cinema, 1992.

Leonard wrote the script with his then-partner Gimel Everett (she sadly passed away in 2013), turning King’s brief tale into the story of Jobe (Jeff Fahey), a gardener with learning difficulties who is used by scientist Dr. Angelo (a pre-Bond Pierce Brosnan) to show his malevolent corporate bosses that his pioneering work in virtual reality should be used to improve people’s minds, not weaponized. Unfortunately, Jobe becomes all-powerful, literally becoming pixels so he can infect computers everywhere and destroy the inferior human race.

Work began in earnest, as the filmmakers built scenes showing the characters inside the VR environment – whether that was racing on spaceships, learning, or having sex. “This was the beginning of the indie use of computer graphics,” says Limber.

“Silicon Graphics was making these machines – my phone probably surpasses it now. Back then, it was a big box the size of a large shipping crate. We had three of those and we’d render all night long. Then, you know, frame 72 would crash and we’d have to reboot.”

“You were writing your own code to do it as you went along,” he continues. “We visited Jeff Fahey at home and we drew a grid on his face with, like, eyeliner. We took these photographs of many expressions and then we just digitized those to get all the facial expression stuff.”

Jobe (Jeff Fahey) in his virtual reality ‘Ccyberjobe’ form in The Lawnmower Man (1992). | New Line Cinema, 1992.

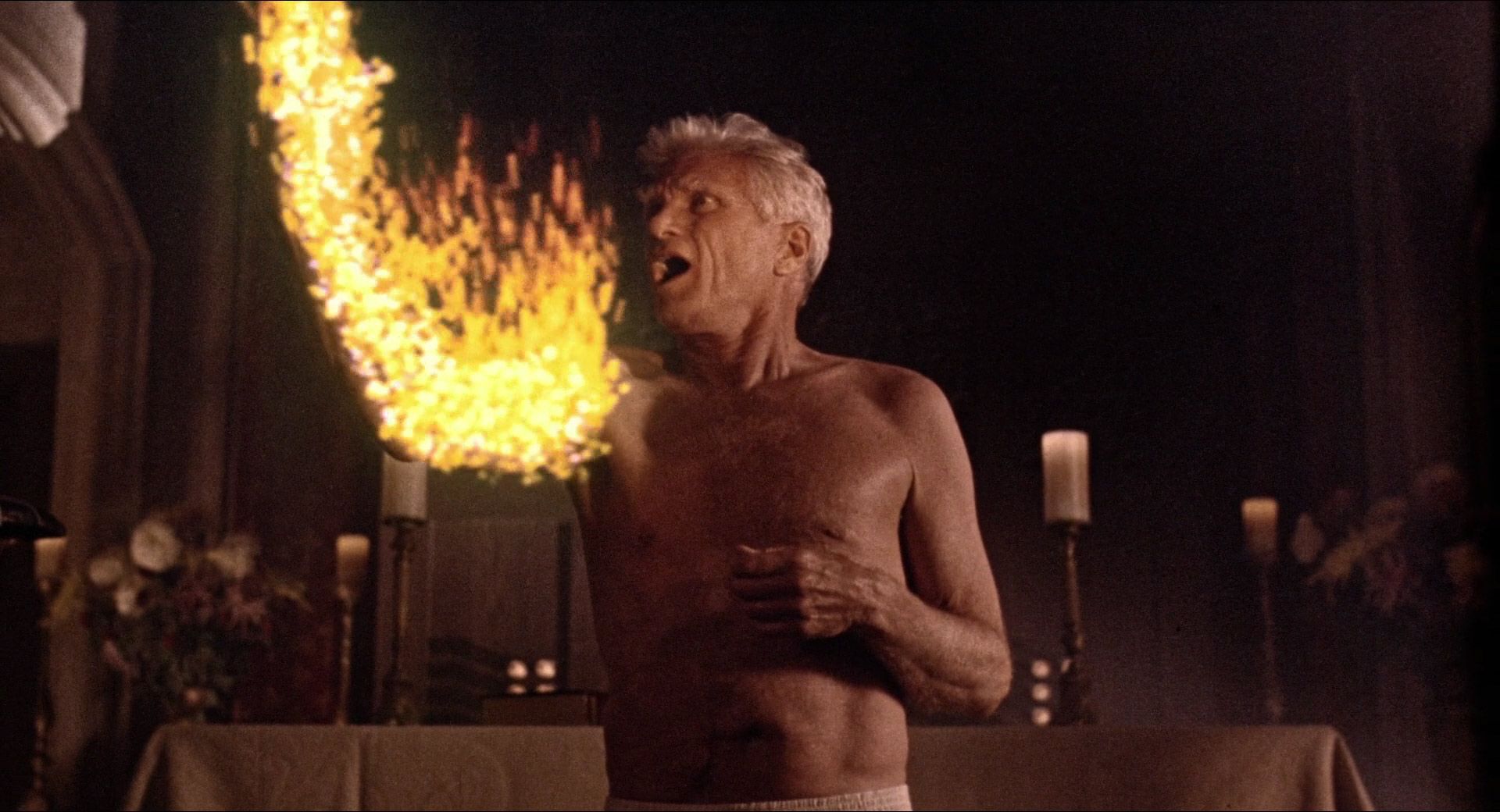

“Cyberjobe – when the character finally transforms from human to only existing inside the computer – is one of the first [on-screen] virtual humans,” says Leonard. “The [virtual] body was done with brute force because we didn’t have well-executed motion capture that we could afford at the time. There is one shot in the film that is done with motion capture, one of the first-ever done. It’s when a priest is set on fire and becomes a fire being.”

Pioneering Motion Capture

In their exhaustive search for innovation, the filmmakers found an Italian motion capture company working in the very much non-Hollywood area of golf training. (The same process which failed Total Recall, finally succeeded with The Lawnmower Man)

“We put the Italian system onto an actor,” says Leonard. “They performed the gyrations and then we added digital fire.”

Father Francis McKeen (Jeremy Slate) is set alight in an early example of motion capture in The Lawnmower Man (1992). | New Line Cinema, 1992.

As the effects companies produced computer graphics and put rough versions of them on VHS, Leonard and his editor – who cut the movie on celluloid film – would sit in the editing suite, look at those tapes and then film them so they had rough versions of those effects which they would eventually cut into the work print, using the Gemini process the director had employed for his original pitch.

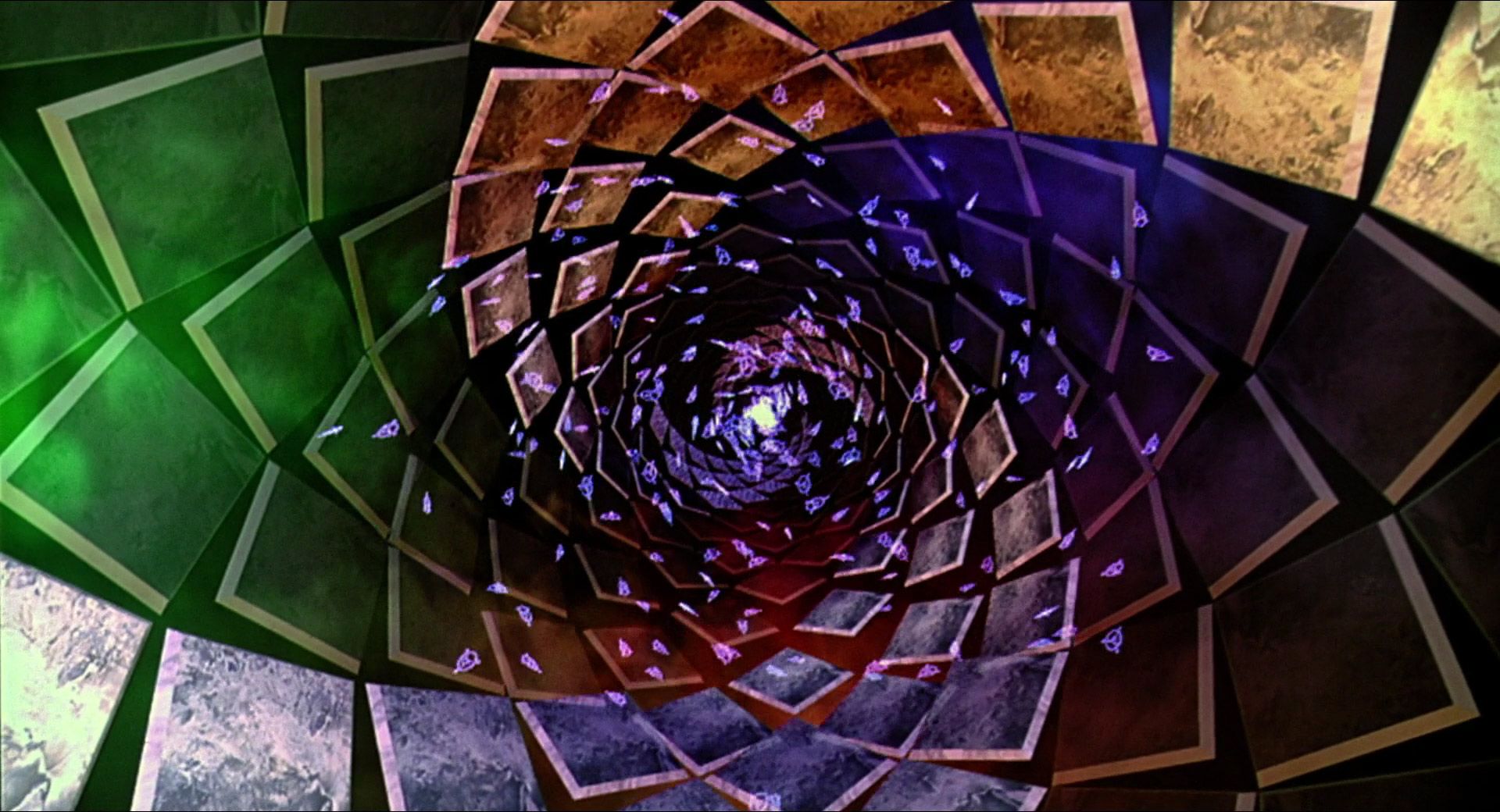

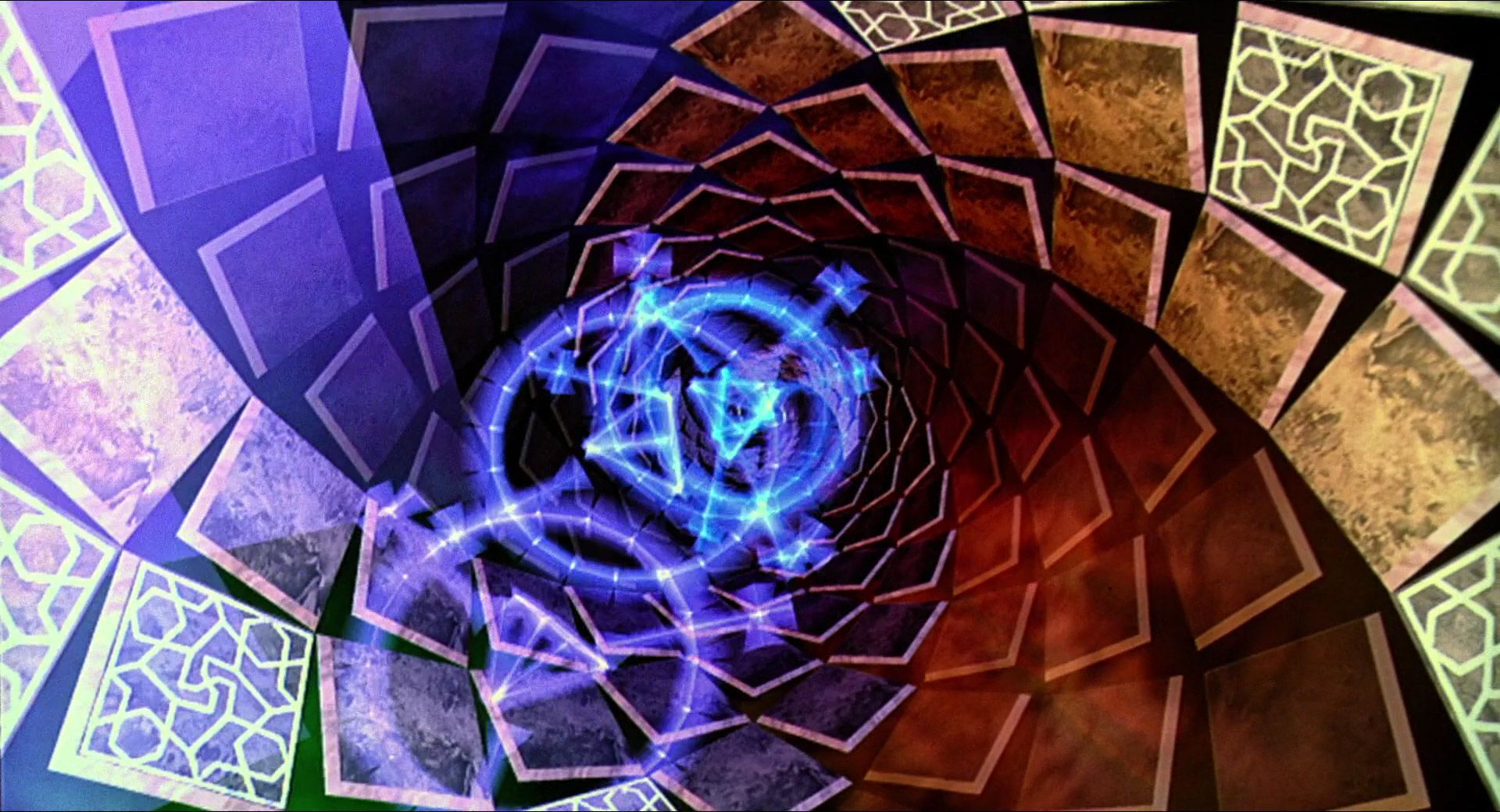

If you watch the film now it may seem as though the effects are dated, but that was actually always part of the movie’s aesthetic.

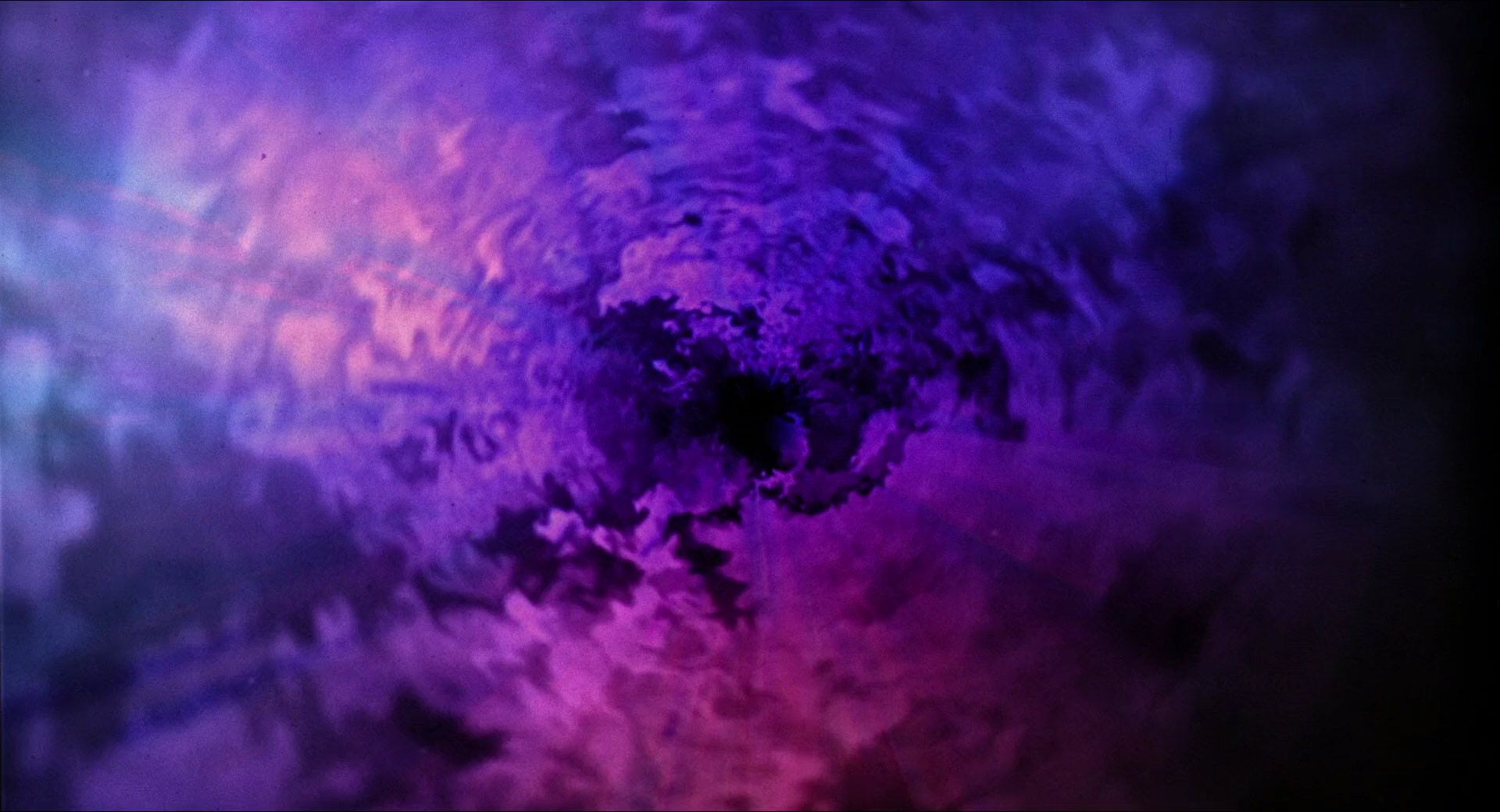

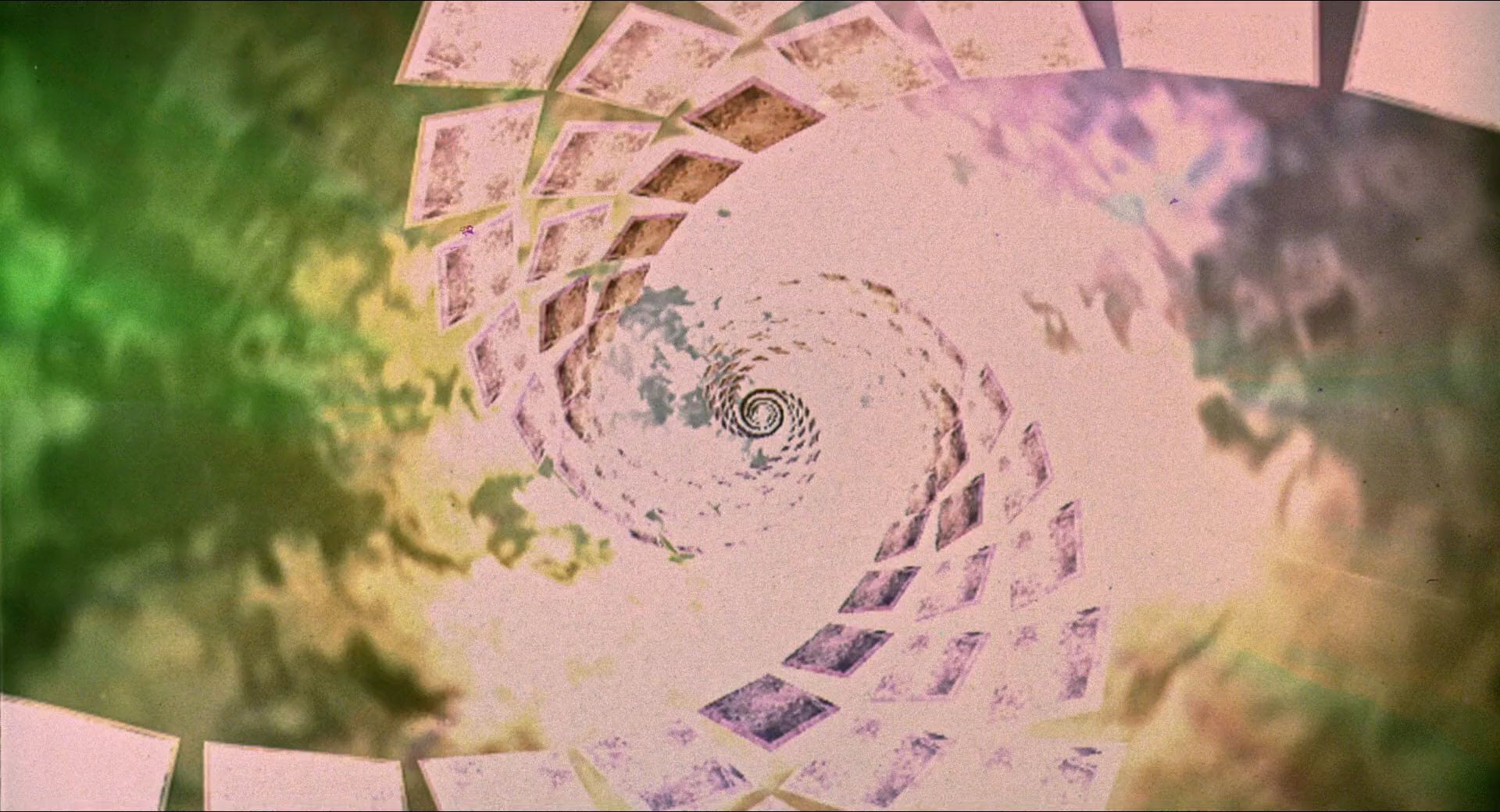

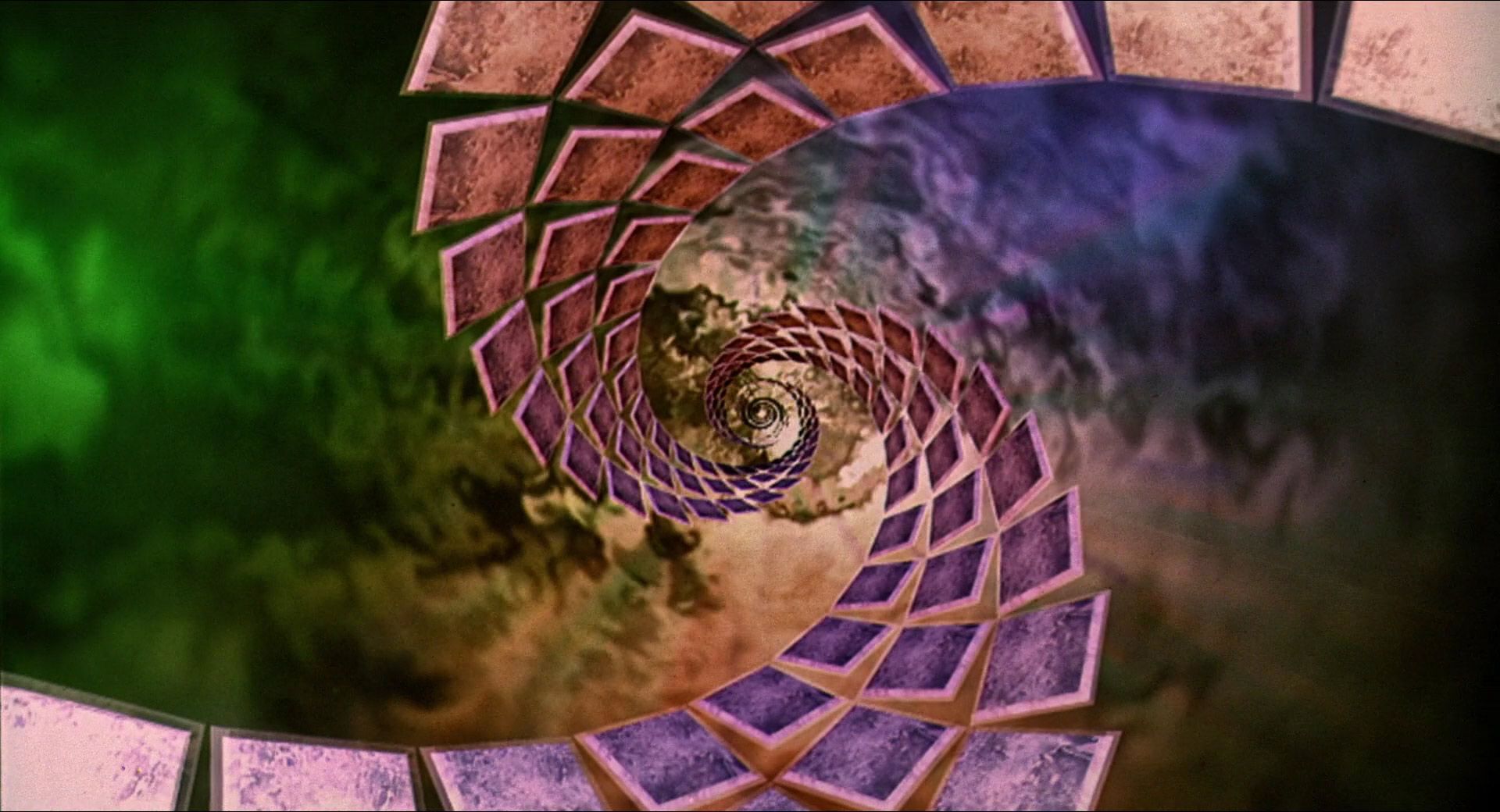

“The way to talk about it aesthetically is that it was cyberdelia,” says Leonard. “It celebrated the look of actual computer graphics as opposed to trying to make computer graphics look quote-unquote real. Even though people can look at the graphics now and say they’re dated, it’s not really that dated because there haven’t been a lot of things that have just explored the computer graphic aesthetic for what it is – an abstract form of art.”

So they were they emulating the VR environments of the time? “No, we were extrapolating,” he says. “But you know what they do look like? They look like the VR environments that are happening now.”

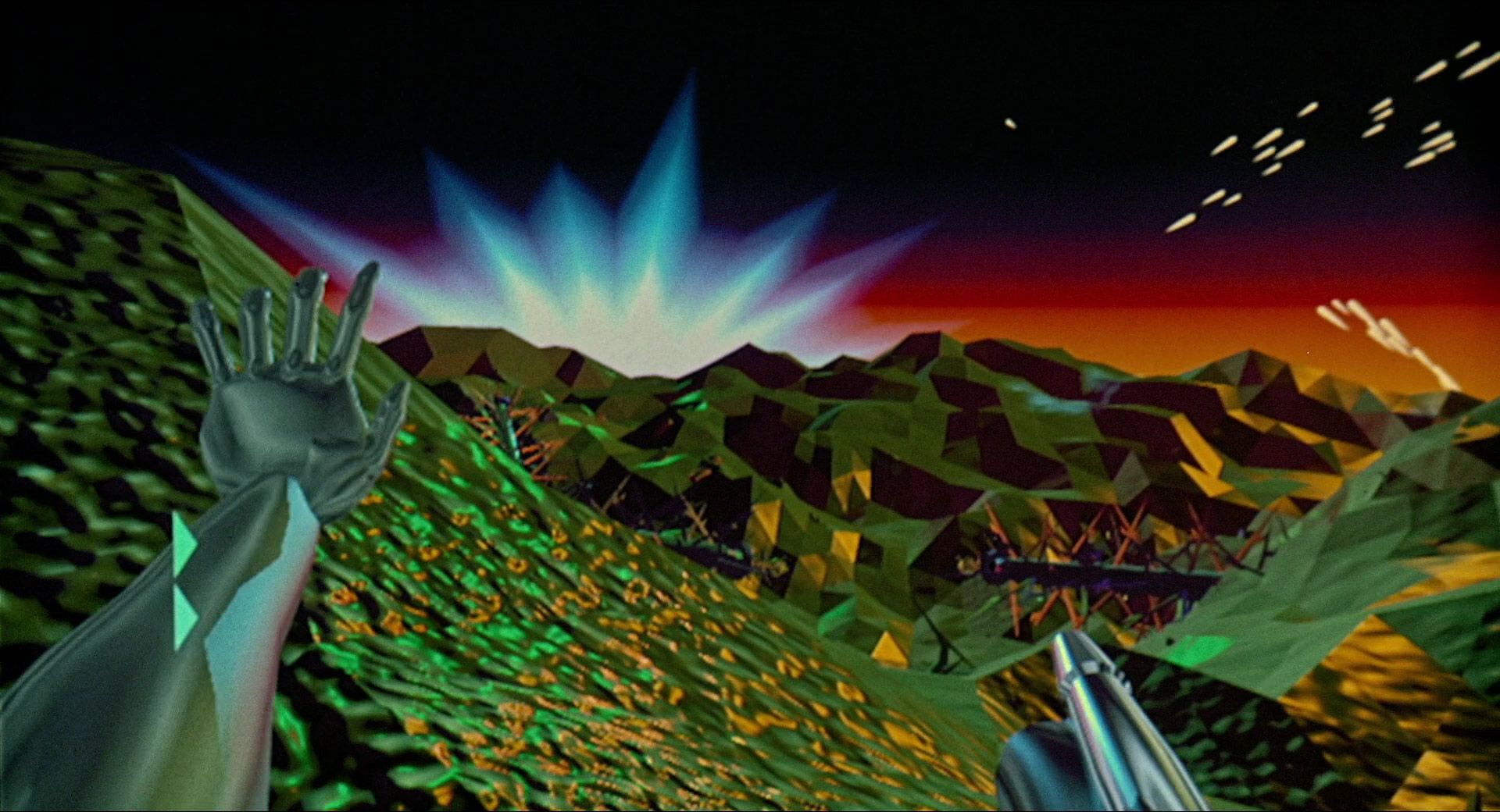

This can be seen in scenes like the ‘brain stem sequence’, in which Dr. Angelo, using VR hands, ‘throws’ information into Jobe’s pulsing virtual brain.

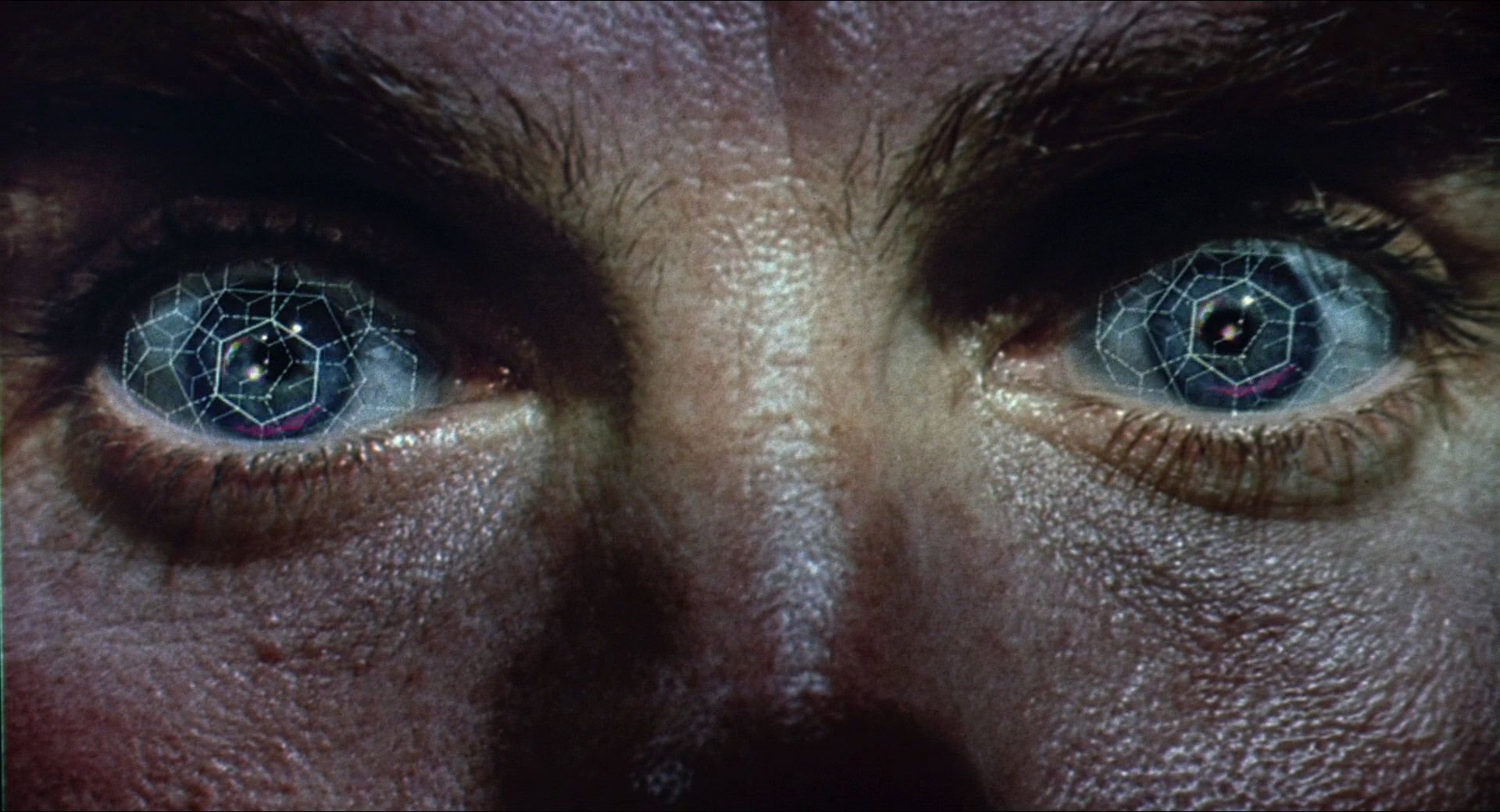

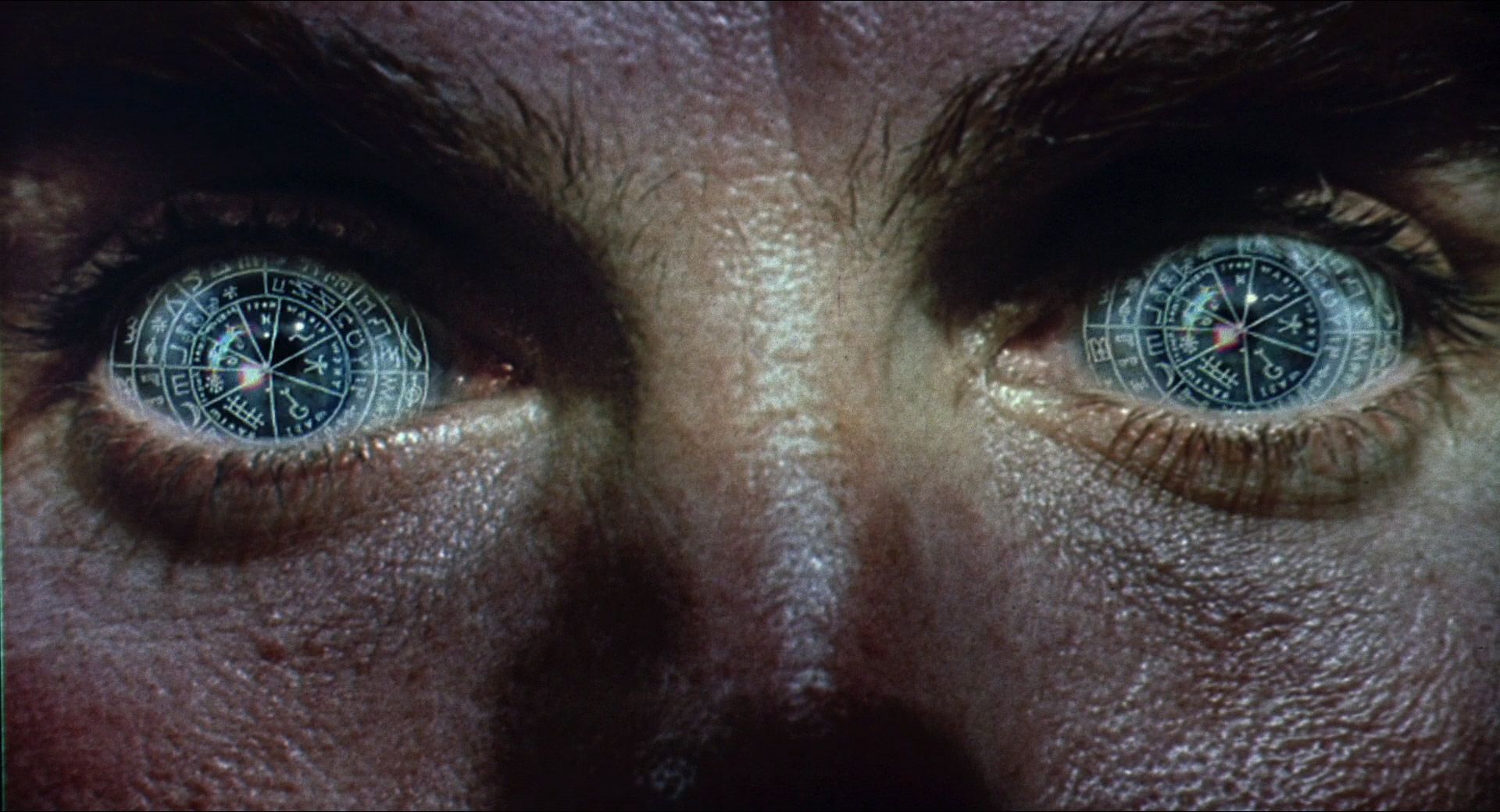

“It’s the kind of interface you see in some current VR environments,” continues Leonard. “As well as the use of streams of sacred geometries being flashed into Jobe’s eyes in VR. We scanned hundreds of actual sacred geometries [created by our] sacred geometry consultant Bob Gulnick – to this day people send me stills of those sequences on Twitter.”

Sacred geometry – based on the belief that certain mathematical formulas in certain sacred patterns prove a divine intelligence – is flashed into Jobe (Jeff Fahey)’s eyes in The Lawnmower Man (1992). | New Line Cinema, 1992.

It’s interesting to remember that alongside these cutting-edge effects were some rather more traditional ones. Tony Doublin did the miniatures work on the film, building a scale model of the Brandeis Institute in the Simi Hills for the movie’s finale, in which Dr. Angelo’s lab explodes as Brosnan and his neighbor – a young boy – barely escape with their lives. Doublin had to build the replica – the original of which they used just after Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991) had vacated it – in two parts and on wheels in order to get it into the parking lot where they could blow it up.

“We didn’t have enough budget for miniature trees,” remembers Doublin. “So we buried buckets in the model and then went around nurseries and found small-leaf trees that were about the right scale. We planted them on the miniature!”

Dr. Lawrence Angelo (Pierce Brosnan), Carla (Rosalee Mayeux), and Peter (Austin O’Brien) escape the burning VSI building in The Lawnmower Man (1992). | New Line Cinema, 1992.

For the climactic scenes where fire takes over the building, they built a corridor and planned to use a series of propane tanks and air mortars, but it didn’t exactly go according to plan. Doublin was by one of the cameras when action was called.

“I thought, ‘I’m going to get under a blanket, just in case’,” he says. The first charge went off on schedule and the fire started to rush down the hallway. “The pyro charge to set off the propane on the second one didn’t go off, so all of a sudden, the gas coming up from the bottom hits the unignited gas at midway, and the camera and I are engulfed in flames. [The people below] started yelling because they couldn’t see me, they were freaking out.

“I’m about to say my prayers and then it’s all gone, because that’s the way propane is. When we had to do take two, I got the hell out of there!”

Lawnmower Man’s Far-Reaching Legacy

Almost 30 years on, it’s clear that while it may not be considered a movie classic (although it was a solid financial hit), the techniques and ideas birthed on the set of The Lawnmower Man have rippled throughout the industry and beyond. Angel Studios’ efforts on the film led to them developing material with Nintendo. The company was bought by Rockstar Games in 2002 and is now part of what’s known as Rockstar San Diego, creating some of the most successful and innovative videogames of all time.

“We were able to play in a space that was normally reserved for much larger productions,” says Michael Limber of The Lawnmower Man. “[We] got a cover of American Cinematographer and Cinefex did a piece on us. Those were huge in the film industry. We did the first cyber sex on-screen, although didn’t really make the money you could make from it!”

Brett Leonard remembers bumping into James Cameron not long after the film came out. “He walked up to me, shook my hand, and said, ‘You bastard, you beat me to VR’,” laughs Leonard. Cameron then took almost all of the Lawnmower Man crew to work with him on True Lies (1994) and Titanic (1997).

Stephen King liked the film too, although he sued the producers for promoting it using his name because he considered it to be so different from his original story, winning a precedent-winning case. Years later, Leonard met him during an event at his talent agency and they laughed about the whole thing. A huge fan, the director asked the author just how he managed to be so prolific. “And he goes, ‘Brett, I’ll tell you a secret’,” recalls Leonard. “‘You get a case of Cuervo and a few eightballs of Colombian, you got yourself a novel!’”

Leonard himself now has his own company, Studio Lightship, for whom he continues to explore virtual reality – he calls it virtual experience – and is known as a VR OG. He constantly meets people in the industry who tell him they got into the business because of The Lawnmower Man.

“When Palmer Luckey got the two billion dollars from Mark Zuckerberg to create Oculus, he came out in the press and said Lawnmower Man was one of his primary inspirations,” says the director. “And then I kind of came to know him and so that set me off on a world speaking tour I was on for many years about VR. It feels like I’m walking into the reality of the movie I made almost 30 years ago.”

Limber, who is now the principal designer at a technology company specializing in 3D maps, agrees. “What’s funny is the things I learned back in those days are exactly the same concepts that are still in play today. It’s still triangles and polygons and texture maps. And when VR or AR becomes common, I think there’s a lot in store that we haven’t seen yet.”

This article was first published on December 18th, 2020, on the original Companion website.