It is difficult to overstate the cultural impact of Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 Ghost in the Shell, now regarded as one of the greatest ever works of science fiction. As a filmmaker myself and lover of the genre, it undoubtedly shaped my approach to storytelling in similarly futuristic worlds. There’s a depth in both its cerebral narrative and beautiful animation that remains a high bar to reach, and its visual and philosophical influence can be seen from The Matrix (1999) and AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001) in the 90s, to recent sci-fi series like HBO’s Westworld.

Having recently immersed myself in dark, futuristic worlds for my own short film, Venus, it’s the perfect time to revisit this classic ‘90s masterpiece. The story of Venus explores similar themes, especially around the autonomy and representation of the body from the perspective of a female cyborg, which I was very mindful of during production. With those considerations in mind, how does Ghost in the Shell represent its ‘shells’, and to what extent is the female form objectified?

The story follows a team of elite security agents, led by Major Motoko Kusanagi, as they track down a mysterious hacker known as the Puppet Master. Much of its short runtime is devoted to philosophical questions about transhumanism and identity, with occasional bursts of gory violence. Ghost in the Shell was instrumental in introducing Western audiences to anime, and along with 1982’s Blade Runner, remains a touchstone of cyberpunk cinema.

Ghost in the Shell in Context

For context, what is ‘cyberpunk’? As a subgenre of sci-fi, it’s generally described as ‘high tech, low-life’. Thematically, it explores futuristic ideas of bodily augmentations, artificial intelligence, and what it means to be human, often against a backdrop of extreme social inequality. Time will tell how much the recent release of the massive videogame Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) will influence public consciousness, but the game encompasses the well-trodden tropes even the most sci-fi-averse audiences will recognize: bustling neon-lit streets in the underbelly of corporate-ruled megacities, with violence and shifty characters around every rain-soaked corner.

Despite technological anxiety being part of our lives more than ever, cyberpunk has remained a rather static genre, thematically and aesthetically, since the release of Ghost in the Shell. The surface-level appeal of cyberpunk is creeping in everywhere we look, from music videos to unironic advertising. How can these retro-futuristic worlds, with all their classical film noir influences and the resulting archetypes, be brought up to date?

In particular, for a genre so interested in the body and the extent to which it defines our identity, there’s a real lack of stories on-screen exploring gender and directly engaging with crucial issues of objectification, rather than indulging in them. Setting out to tell such a story, Venus is about the relationship between a mother and her daughter, Iris, who is torn out of her idyllic digital world and uploaded into a stolen synthetic body designed for sex and violence. The film’s co-writer, Tara Shehata, and I intended to tell a character-driven and thrilling cyberpunk story from a female character’s perspective, breaking away from the usual ‘male gaze’ that dominates these worlds.

Ghost in the Shell immediately sets itself apart from much of the cyberpunk ‘canon’ with Motoko driving the narrative but is her body sexualized, and to what extent do her mind and her body define her identity?

In the year 2029, an ‘organic’ human is an anomaly; most of the population have “cyberbrains”, and Motoko herself is a cyborg with 100 percent artificial components, though indistinguishable from humans. We witness her “birth” during the film’s title sequence: an unambiguously robotic body is intercut with the visual of a brain being scanned and converted into code, concisely synthesizing the mind’s ‘ghost’ and the body’s ‘shell’. The next shot tilting up from her legs to her breasts would be typical of the male gaze if it wasn’t for the fact that this is a skinless body with exposed muscles and robotics: decidedly unsexy (to most, I assume).

The liquid process of her construction, which the Westworld recently paid homage to, melts and flakes away to reveal her “perfect” female form. It is far more typical of the way women are often framed in sci-fi, her rotation allowing the camera to linger on every angle of her curves. However, it could be said more generously that the way the scene is constructed, with its standout score creating an air of sadness and spirituality, presents this objectification in the context of a birth; Motoko plunges into the water in a fetal position as a humanizing and naked newborn, yet the image is stripped of its innocence through its voyeurism. It is one of several scenes in the film signifying birth or rebirth, in this case, a perfect and meticulous construction of a body – it is literally a military operation, and she is subjected to this gaze and lack of autonomy from the very beginning.

Form and Function in Major Motoko

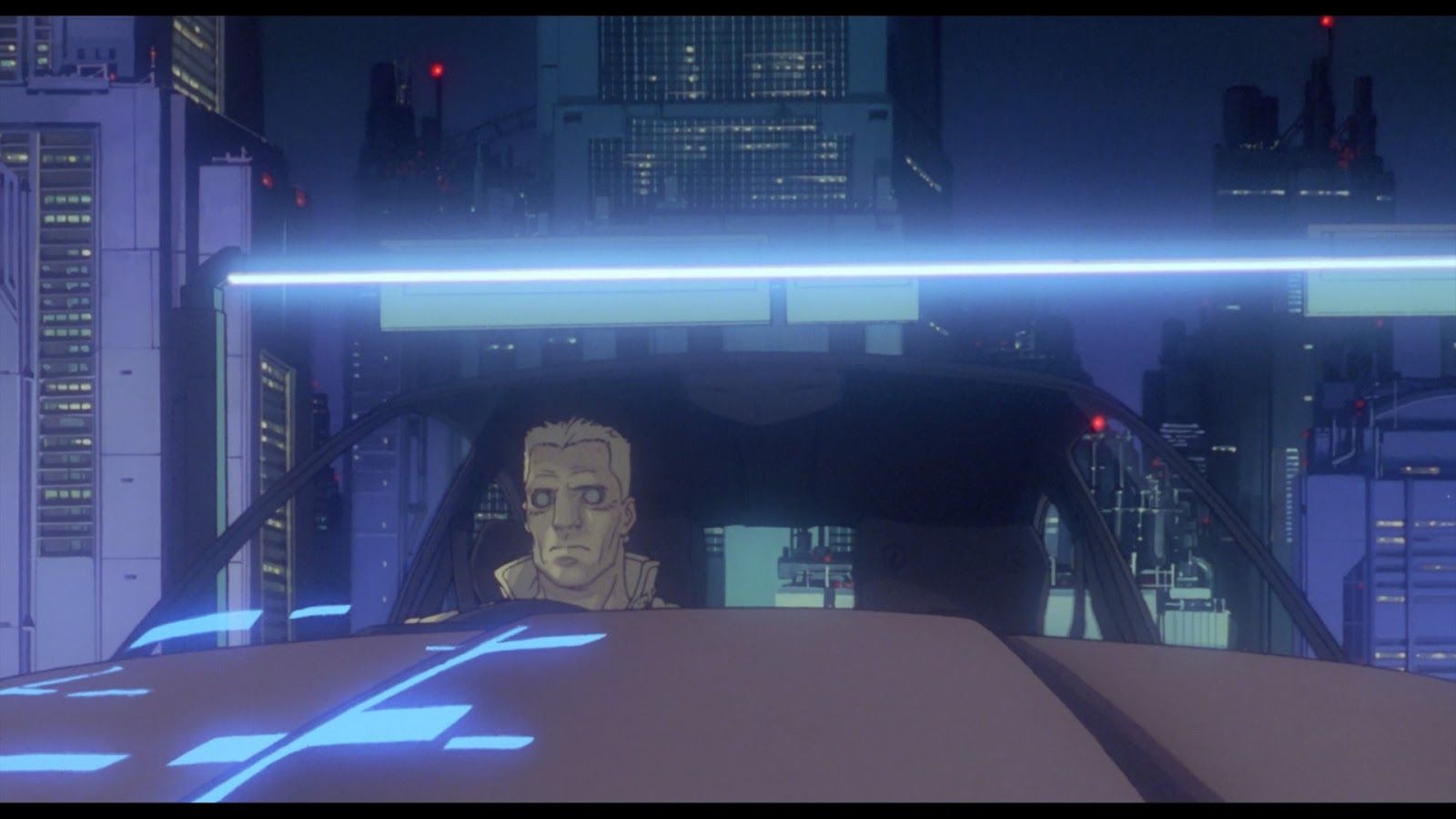

Motoko, in body and brain, is a weapon and property of the government, and if she were to retire, there would be nothing left of her once their assets are returned. She herself does not view her “state of the art” body as anything more than a tool, which she operates with deadly precision and the same strength as her hulking muscular friend and partner in crimefighting, Batou. While they both have autonomy and superhuman abilities, their bodies are defined by their corporate dependence, rather than gender.

During one of the most iconic scenes of the film, which deserves an entirely separate article to fully unpack, Motoko sees an exact double of herself while sailing down the city’s canal. If the body is as tied to her identity as the mind, then how could she be an individual in a mass-manufactured shell? This question is further underlined by Oshii’s decision to end this scene on the static image of limbless mannequins. There are plenty of mirror images of Motoko throughout the film as if she’s looking for a soul behind her eyes and trying to break through a barrier to her true self, including a striking moment in which Motoko rises up to meet the water’s surface while diving. Being underwater in a heavy cyborg body, she “imagines becoming someone else”, but the visual of her breaking through the water clearly brings to mind her artificial birth; even her natural surroundings take on artificial significance through her manmade body and eyes.

On the surface, Motoko’s gender and female form is irrelevant in defining her character; she commands unquestioned authority in Section 9, an agency otherwise composed entirely of men, and her body is never used seductively during her missions. Although the gender associations of Batou’s towering stature and Major’s athletic build are present, they are equal in strength and ability. She herself seems oblivious to social conventions of the body, casually changing out of her swimsuit in front of Batou, who looks away out of modesty. The camera cuts to share his perspective as he looks up at the gleaming monolithic skyscrapers, despite the city being as artificial as the Major’s own body. Though the film is essentially sexless, nudity in this world remains a taboo despite reducing the body to a “shell”.

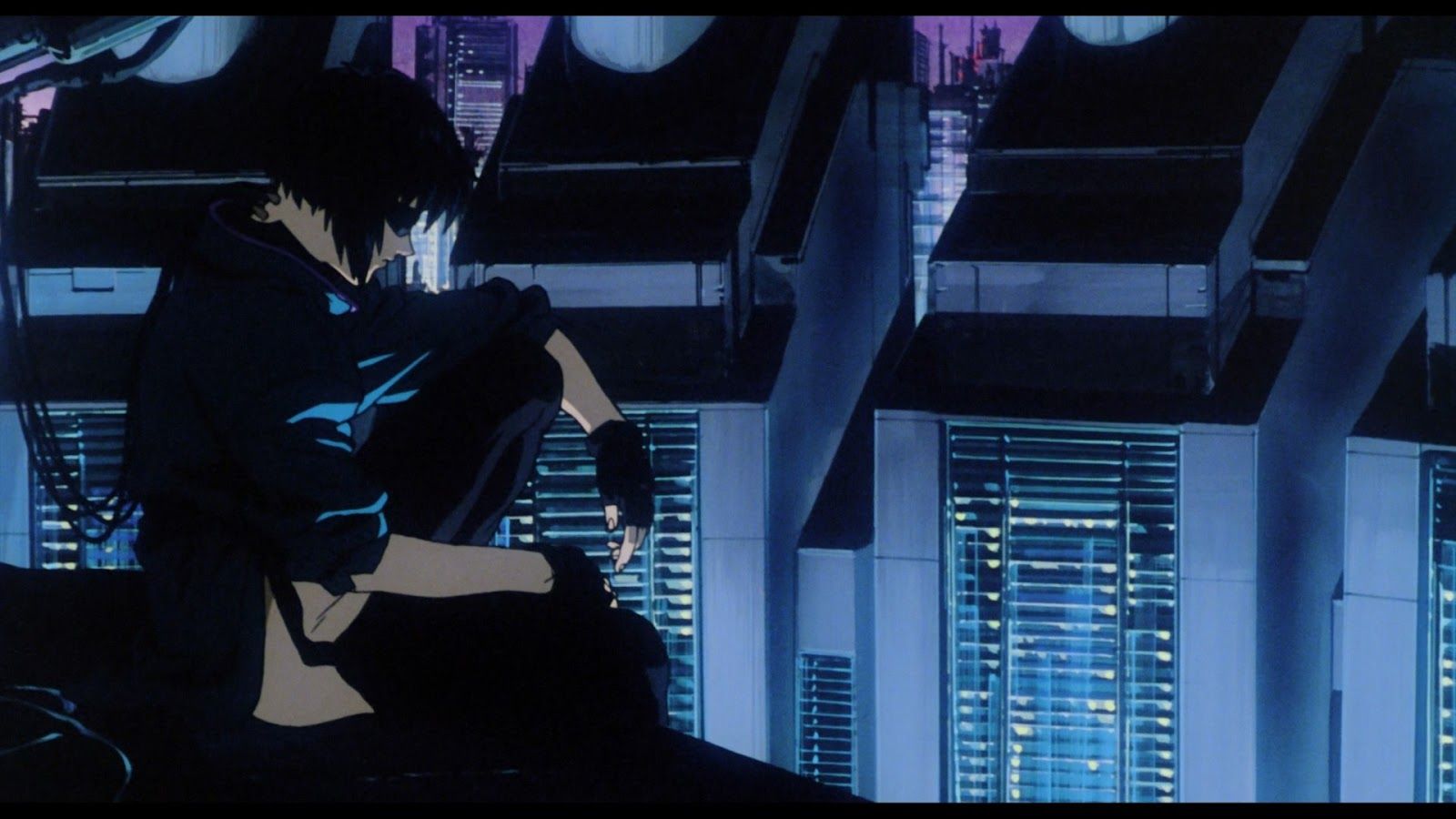

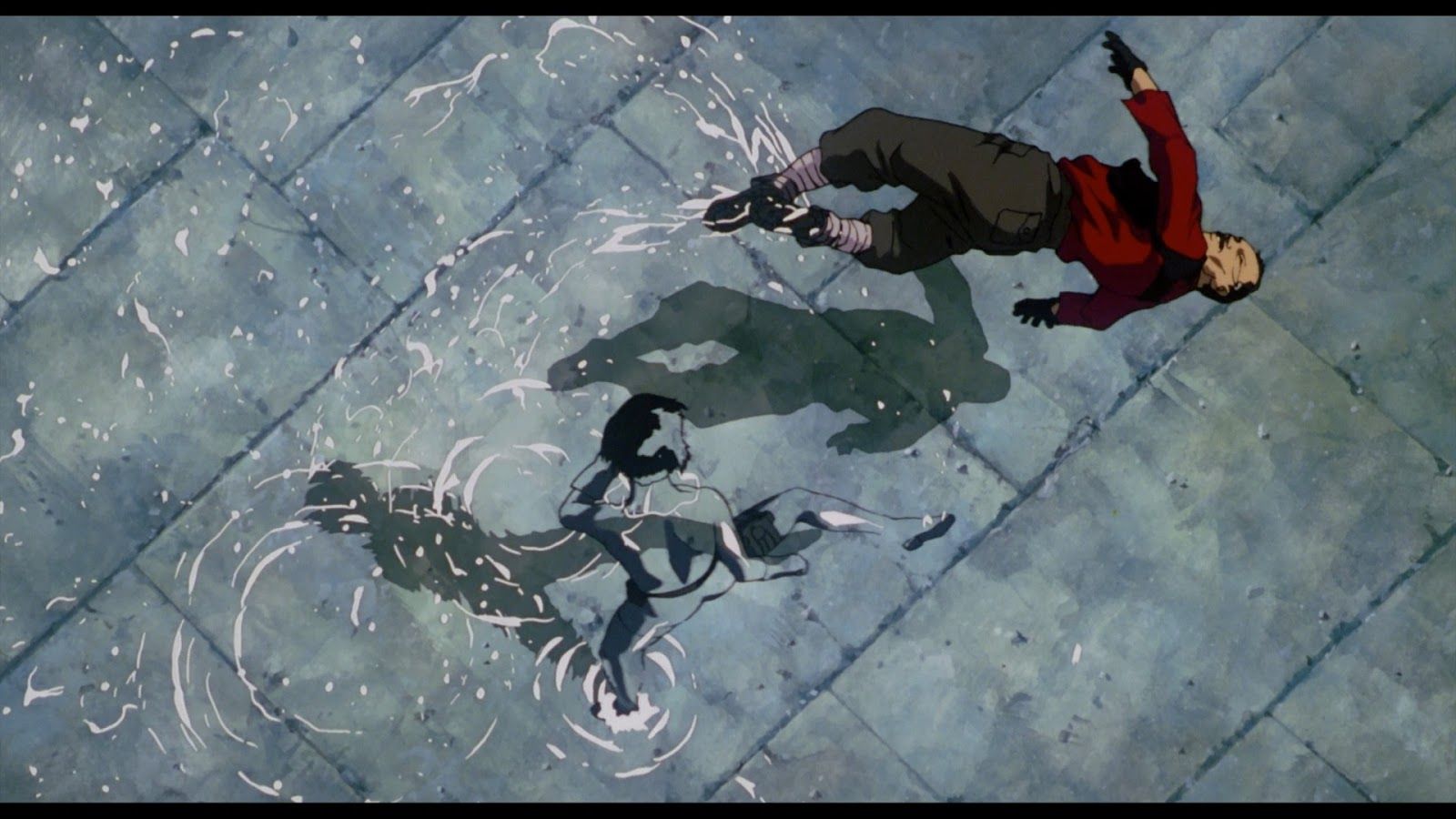

One of the most interesting concepts in relation to Motoko’s body is the ability to turn invisible using a skin-tight suit, seen in the brilliant opening scene as she assassinates her target. She can only turn invisible when she’s “nude”, interestingly subverting the voyeuristic notion of the female body as something to be looked at by men, and instead enabling total freedom in one’s body – which in this case, is used for spying and violence against them. When she invisibly hunts down a fleeing criminal in a later scene, the surreal sequence of his body being tossed around in shallow water makes Motoko’s shadow and brief outline seem omnipotent and impossible to fight or understand.

Motoko’s stature and clothing are rarely sexualized during the film, though later iterations are less successful; the otherwise enjoyable first series of Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex is marred by Motoko’s incredibly sexualized (and surely not tactical) leotard and stockings costume, framed by an often leering camera. It is also worth noting the disservice of this original film’s VHS and DVD cover – the tagline acts as both a censor and spotlight for her breasts, despite never being fully naked in combat during the story.

Subverting the Sexualized Cyborg Body

It can even be said that the way Motoko is drawn is rather masculine, with rigid features, a wide neck, and no suggestion of makeup. Aside from the invisibility suit, her clothing is either loosely casual or tactical rather than form-fitting, without much personality imbued.

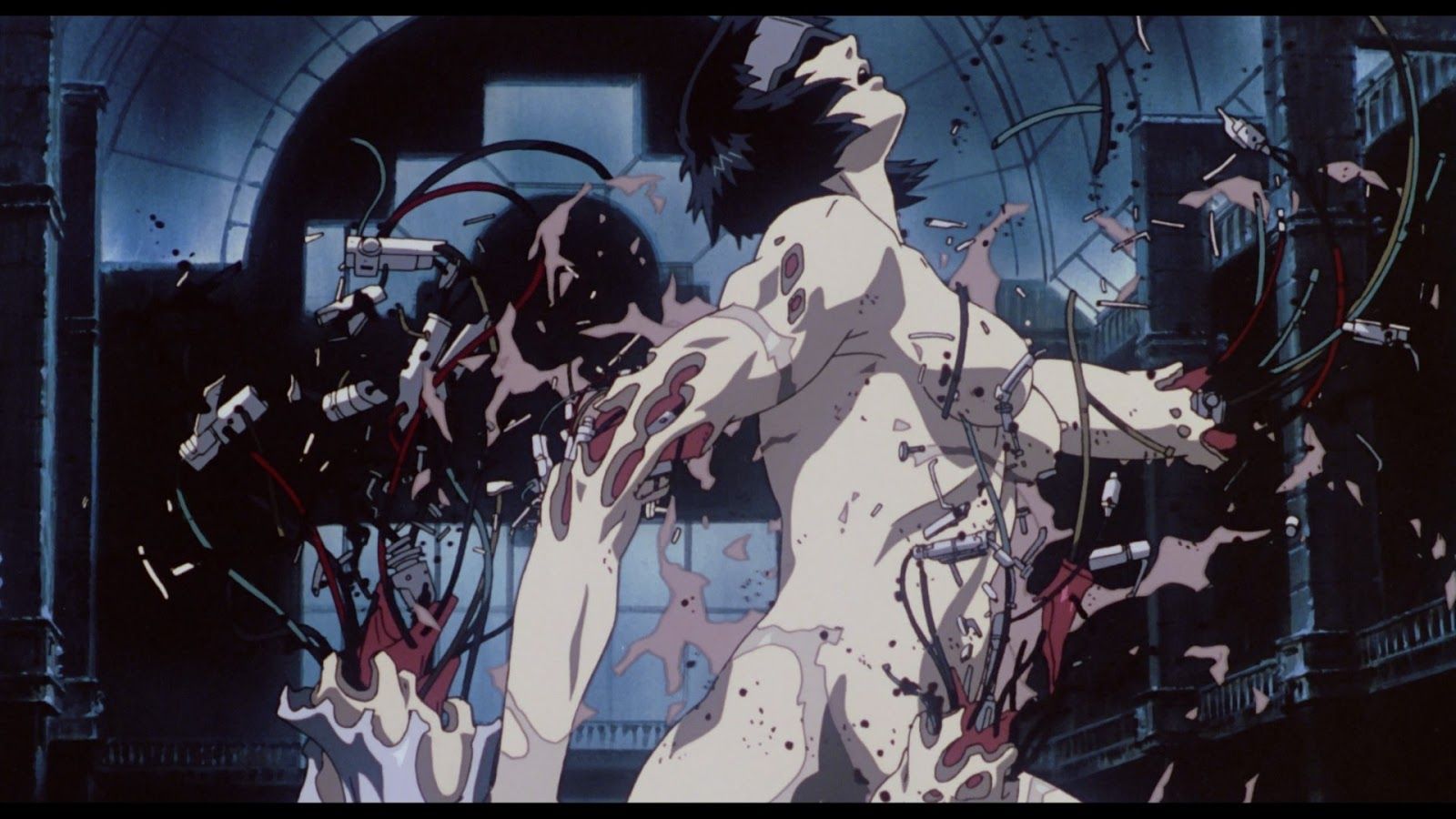

The film’s climax, in which she attempts to destroy a tank, results in her body being torn apart by the effort, her muscles bulging out of her skin and her limbs pulled apart accompanied by suitably squelching sound design (one of the best episodes of The Animatrix (2003), ‘World Record’, takes direct inspiration from this moment). The shot focusing on her almost naked breasts and straining arms could be read as gratuitous, bringing to mind scenes of violence against women that seem to plague sci-fi; Netflix’s Altered Carbon and Love, Death and Robots, and Mute coming to mind.

There is a distinction, however; while it is a disturbing moment for the viewer, having closely followed a character who in any usual context would soon be dead, for Motoko herself the body is disposable. She is focusing solely on her objective and the graphic imagery is not violence against her; she has simply reached her limitations when up against stronger technology. Her bulging muscles present us with a very masculine image offset with her center-framed breasts, and this decoding of gender is a recurring theme in the film.

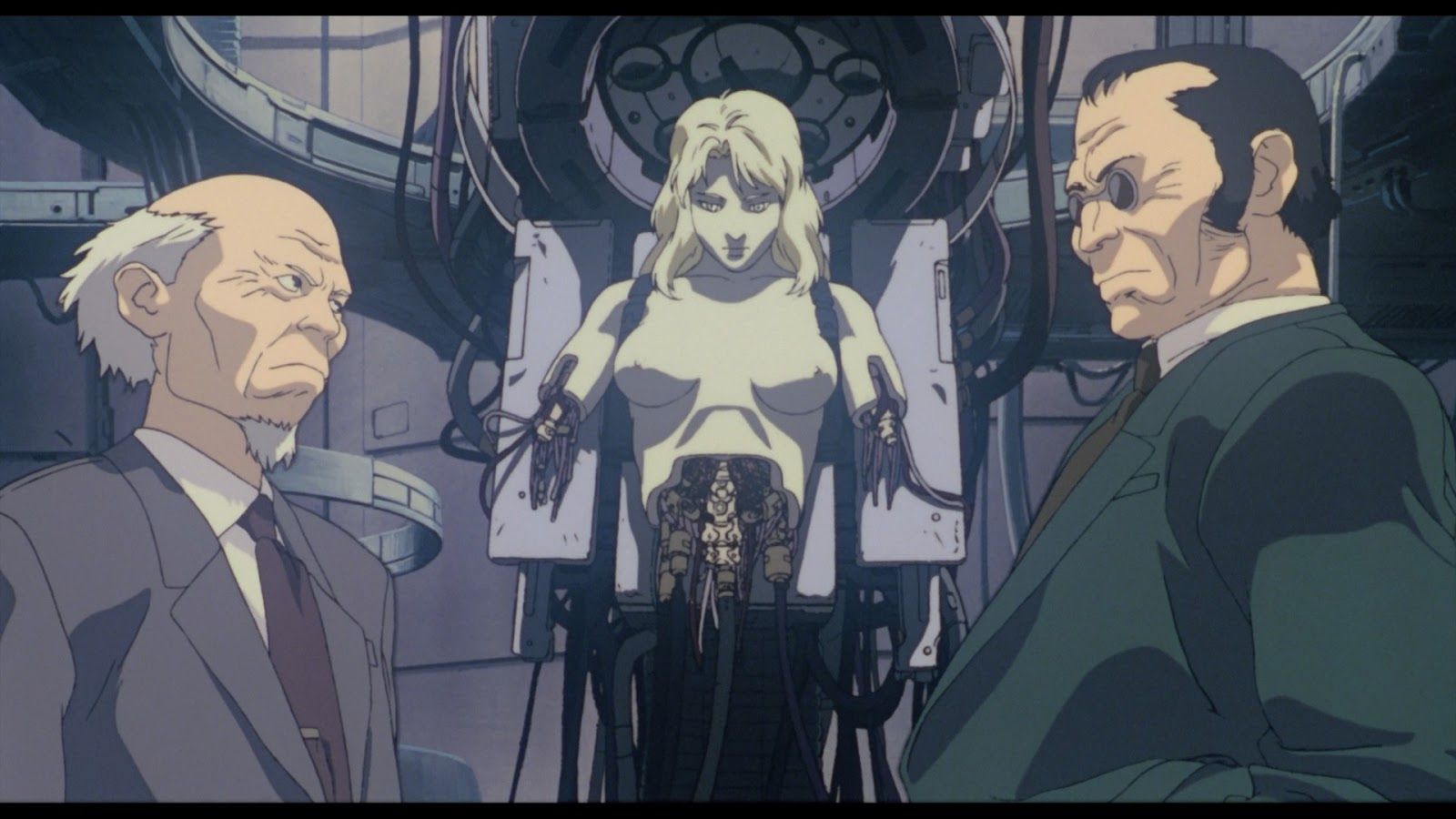

The Puppet Master is the closest thing the film has to an antagonist and blurs the gender boundaries of the body and mind. “Created in the sea of information”, cyberspace, the self-aware consciousness steals a cyborg body to plead its case for political asylum. This stock body, with ethereal beauty in contrast to Motoko’s sternness, deliberately jars with the philosophical questions coming out of its mouth.

However, for all its possible readings and bare minimum nuance compared to other objectified women in science fiction, it is impossible to avoid the fact that the only female characters (or at least bodies) in the film are frequently nude and surrounded by well-covered men. In the case of the Puppet Master’s body, it is partially disassembled with nothing below the waist or elbows, with only loose cables trailing out of them. The body is physically powerless and immobile, stripping it of all autonomy.

A shot of the Puppet Master’s body in profile, accentuating both breasts with one of the suited men who dismantled it in the foreground, is immediately followed by a shot of his hands growing multiple robotic fingers, enabling him to type with extreme speed – it’s a stark contrast between aesthetic and functionality, female and male. When the Puppet Master’s body is electrocuted, it shakes and squirms unnaturally, treated like a slab of meat – which it is from the characters’ perspective – with its breasts prominently framed from below. While a body is just a body, no camera is objective, and there is a responsibility to at least interrogate a shot such as this within the narrative – especially as a male filmmaker.

As one of those myself, it was important to me that the story of Venus was always aligned with the protagonist’s perspective, despite the objectification of the body in this dark future. Much like Motoko, who states “the way I’m treated [is] the only thing that makes me feel human”, Iris’s body is deemed corporate property and built to fulfill a function. With her body being that of an android designed for pleasure, the way she is treated is decisively inhumane and entirely defined by her form; perceptions of the human body have reached a point where she cannot convince another character of being ‘real’ and is dismissed as someone has messed with her settings, reducing her to an imitation of a person in the eyes of others. We carefully considered the presentation of both Iris and the other “Dollee” androids to raise the issue of objectification and creating enough context without ever indulging in it; as a small example, in the scenes in which she’s standing on display in a booth, we share her point of view looking outwards, rather than a male gaze looking inward.

Looking for Life Beyond Biology

The Puppet Master’s male voice in a female body is more interesting when it comes to shifting the relationship between gender and identity away from the heteronormative: “The sex of the perpetrator isn’t known and remains undetermined,” one of the scientists states. A digital consciousness has no gender (and apparently Puppet Master’s voice varies between male, female, and a mixture of both on different dubs), and their shell is decidedly unrelated to their identity – much like Motoko views her own body and its limitations. Yet the Puppet Master still desires a physical form despite its infinite knowledge.

As purely data, its consciousness is vulnerable, and all copies are susceptible to being wiped at once. Ironically, despite its infinite knowledge, it is the shell that frees it from extinction by merging with Motoko, allowing it to “bear offspring into the net itself. Just as humans pass on their genetic structure.” A new kind of life. Women are far too often represented in narratives as baby-makers and passive mothers, side-lined by a male protagonist, which is not at all exclusive to sci-fi. Avoiding this pitfall, the presumably infertile Motoko’s humanity is not ‘validated’ by gaining the ability to give birth, nor has she ever shown an interest in it. Instead, she agrees to ensure a new kind of life can continue to exist, one which gives meaning to her human/cyborg existence.

The anxiety of human and technological synthesis is embodied earlier through Motoko’s concern that her own mind may be as artificial as her physical form: “Maybe I died a long time ago and somebody stuck it in this body.” At what point does imitation become reality, where does the soul begin, and do memories define us? Without delving into Descartes and philosophical questions as old as humanity, which I won’t be able to get my head around here or ever, her doubts are brought into focus by the Puppet Master’s proposition of both minds merging.

Motoko’s fear that this will result in her losing her identity, to which the Puppet Master responds that we are always changing, and even if her memories are fake, our present actions are what matter and define us; it’s a sobering and relatable concept amid the impossibility of imagining a new kind of consciousness. This first instance of transhuman evolution allows both of them to grow beyond the limitations of sexual or gender identity; Motoko, who previously felt “confined, only free to expand myself within boundaries,” is reborn into something limitless.

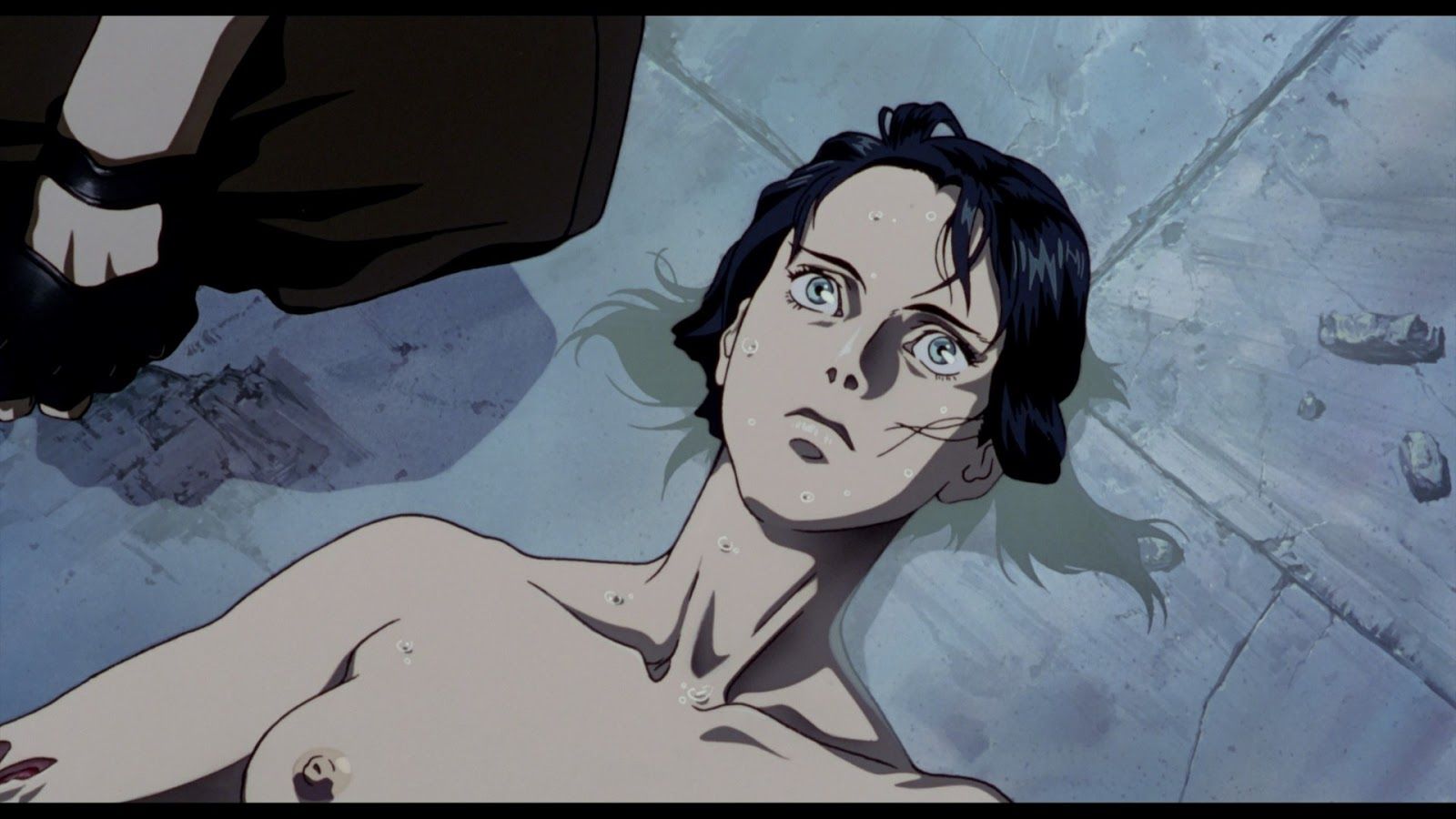

This “rebirth” bookends the birth in the opening sequence, but is unlike the meticulous process of her body being formed, and ultimately violent. Their faces overlap, merging within the frame itself, a surreal image of two becoming one in body and mind. The fact that nothing in this image is truly organic only highlights how limiting our definition of identity is, while we are still invested in the interactions between two human-looking characters. Both heads being bloodily blown apart by Section 6 snipers represents a violent change in order to be reborn as something beyond their ‘shell’.

The Legacy of Ghost in the Shell

The notion of painful rebirth from between the ‘ghost’ and ‘shell’ was also in mind while writing Venus, framing a shift from a simulated reality to the real world almost as a twisted coming-of-age moment, pushing the change from an adolescent to an adult body to the extreme. Iris is suddenly thrown into a physical world, breathing real air in an unfamiliar body; transitioning from a digital world entirely in her control, to a harsh reality in which she must fight for autonomy and against her body’s design.

The opening text of Ghost in the Shell, explaining that “the advance of computerization, however, has not yet wiped out nations and ethnic groups” suggests an inevitable separation from the restrictions of identity via technological advancement, and Motoko’s existential doubt after her immaculate construction contrasts with her newfound assurance in herself by the end of the film. Though she remains restricted by her shell as government property – and is symbolically reborn into a child’s body, the only shell available on the black market – the final shot of her gazing over the sprawling city is optimistic. “The net is vast and infinite”, as are the possibilities for her and humanity in both body and mind.

Ghost in the Shell is a landmark of anime and sci-fi cinema, and there’s no doubt it engages with plenty of interesting ideas concerning the body and the influence of identity, amongst many other compelling ideas. Nonetheless, it still indulges in objectifying tropes that are still far too common today. Motoko is perhaps too entrenched in sci-fi male fantasy to truly be a feminist icon.

Check it out on Kickstarter.

There have been several standout sci-fi films over the last decade exploring these ideas concerning the female body, like the brilliant Ex Machina (2014) and Archive (2020), and the most interesting element of Blade Runner 2049 (2017) was Joi, a digital companion designed to be the perfect partner. A moment in which a giant holographic and naked Joi casts doubt over the authenticity of her relationship with the protagonist is already an iconic image, but these stories remain very much aligned with a male perspective. What if the version of Joi we had been following throughout the story was instead the one looking up at her enormous, sexualized self?

That question was formative for Venus, which I’m now hoping to develop into a feature film while the short is submitted to festivals. While I don’t think any stories should be off-limits to any filmmaker (though the ratio of male to female directors/screenwriters is terrible and shows how much the industry is in desperate need of reform), men, in particular, have a responsibility to be aware of the male gaze.

Despite its dark vision of the future, Ghost in the Shell’s legacy has paved the way for a new generation of fresh and progressive stories, in the most progressive of genres.

This article was first published on February 18th, 2021, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂