The mid-1970s and Gerry Anderson’s career was in flux. The Supermarionation series that had made him a household name were no longer in production, and his first two live-action series (UFO and Space: 1999) had been popular but not runaway successes, UFO being replaced by Space: 1999 and that second series having not received a firm recommissioning.

Anderson’s next project fell into this production gap: a potential pilot for a series that never made it to fruition. However, in a crowded field of interesting-but-flawed Anderson projects that never were, The Day After Tomorrow – shown in the UK as Into Infinity – has the most potential. A surprisingly emotionally and scientifically engaged exploration of humanity’s near future, it takes the exciting design and special effects of Space: 1999 and refocuses them onto a scientific framework combined with Lost in Space-style family-in-peril. It’s a lost gem.

First broadcast as part of NBC’s after-school special series Special Treat, which would include everything from documentaries to classic literary stories, the episode was originally seen by NBC executive George Heinemann as part of seven one-hour episodes designed to teach children science in the form of an action-adventure: not too divorced from early concepts of Doctor Who or Star Trek: The Original Series. NBC would further promote the series by distributing leaflets containing the science behind the shows to schools. As Anderson had not received a guarantee from ITC Entertainment that there would be a second series of Space: 1999, Anderson and Space: 1999 script editor Johnny Byrne came up with an idea that could – if needed – go to series.

Scientific Accuracy in The Day After Tomorrow

In a 1979 edition of Starlog, George Heinemann spoke on his reasons for producing the special:

“I wanted young people to watch this film on television and find it exciting enough that, in the course of viewing the program, they would be able to acquire an understanding of Einstein’s theory of relativity. When the teacher wrote E = mc2 on the board, I wanted the young viewer to recall the program and say, ‘Yeah, I saw a programme about that. I want to learn more about it,’ instead of, ‘It's just one more thing I have to memorize and what good is it gonna do me?’”

However, as neither Byrne nor Anderson had a scientific background, it was more difficult to conceive of textually than a pure sci-fi-fantasy like Space: 1999: Byrne recalled, in a 1993 edition of TV Zone, that “Once I got the go-ahead I suddenly realized I knew very little about the theory of relativity... I went out and read Relativity for the Layman, and realized I was in deep trouble because there were so many aspects of it.’ Professor John G. Taylor of the University of London, known as both an expert on black holes (following a successful book on the subject in 1973) and investigator of parapsychology, was engaged as scientific advisor.

However, like many a televisual scientific advisor before him (see The Tomorrow People for a truly staggering inclusion of the role—no one in TTP even gave a hoot for accurate science) Taylor was unable to contribute much, and Byrne instead focused on including the Doppler effect, the death of planets, and the potentials of black holes. Time dilation was also included, a factor which again added an emotional side into proceedings: Dr. Anna Bowen (Joanna Dunham) emphasizes that in even the earliest possible return time (fifteen years) that “My parents your father… they’ll be old. Even dead by now.”

Byrne wrote that part of the special’s scientific ethos was writing the characters to only give partial explanations of the phenomenon they encountered, encouraging the audience to research the topics themselves—perhaps through a handy NBC branded leaflet?

The Theory of Special Relativity suggests that light, either refracted or emitted, travels at the same velocity whether the object is moving or stationary: tl;dr, the speed of light is absolute and nothing can travel faster. Although E=MC2 is the most famous element of this theory, the consequences it suggests for science fiction are much more fantastical, such as Time Dilation, wherein time slows down for the crew of the Altares relative to those left on Earth. These elements become plot points but are not expanded on.

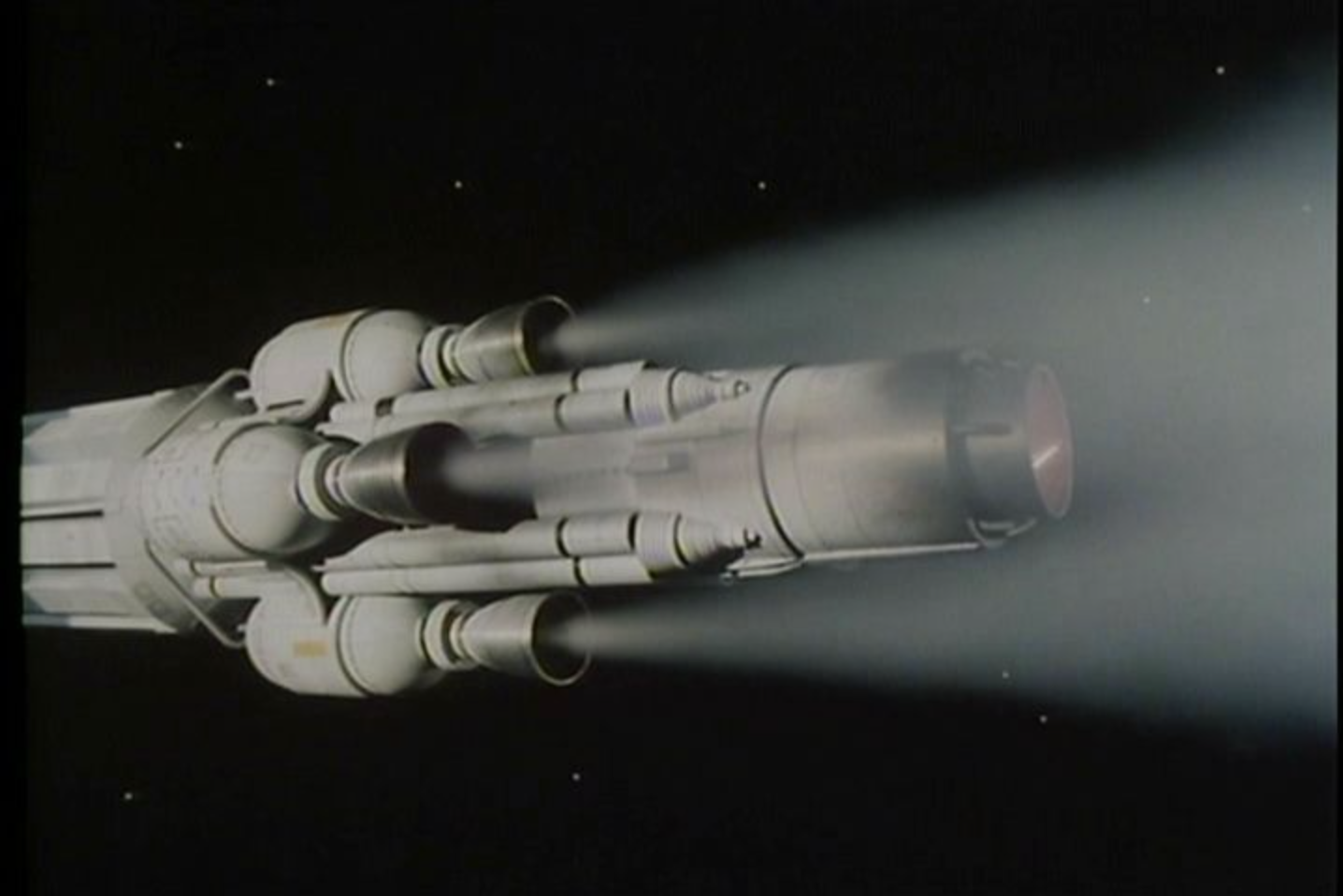

Altares is the first spacecraft to ‘harness the limitless power of the photon’; moving at the speed of light, which may cause those ‘effects predicted by Einstein's theory of relativity – effects that could shrink the very fabric of space, distort time, and perhaps alter the structure of the universe as we understand it.’

The “lightship” concept is derived from Eugen Sanger’s reformatting of Einstein’s theory into the concept of a ‘photon rocket’, the “mutual annihilation of matter and antimatter to produce an energetic gamma ray ‘exhaust’ which like all other photons of electromagnetic radiation (visible light, radio waves etc.) travel at the speed of light.” Impossible in real life due to the failure to channel gamma rays into a useful exhaust rather than turning the ship into a bomb, if possible the photon drive could accelerate a ship to 95 percent the speed of light- although with no propellant left for orbiting around Alpha Centauri or returning to Earth. Similarly, only Pluto goes through the Doppler Effect of distorting light, with the asteroids and sun remaining only one color.

If as Carl Sagan estimated a trip to Alpha Centauri would take four years, then why do the crew fail to age?

The ship is hit by a meteor shower: meteors impacting at 95 percent the speed of light would almost certainly cause catastrophic damage to the Altares. The ship’s acceleration is implausibly quick, and the crew would be crushed beyond existence by the G forces, rather than being lightly blown with a hair dryer.

The Production of The Day After Tomorrow

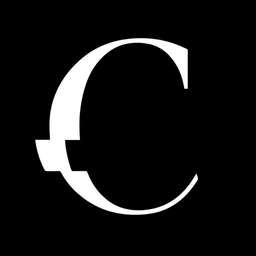

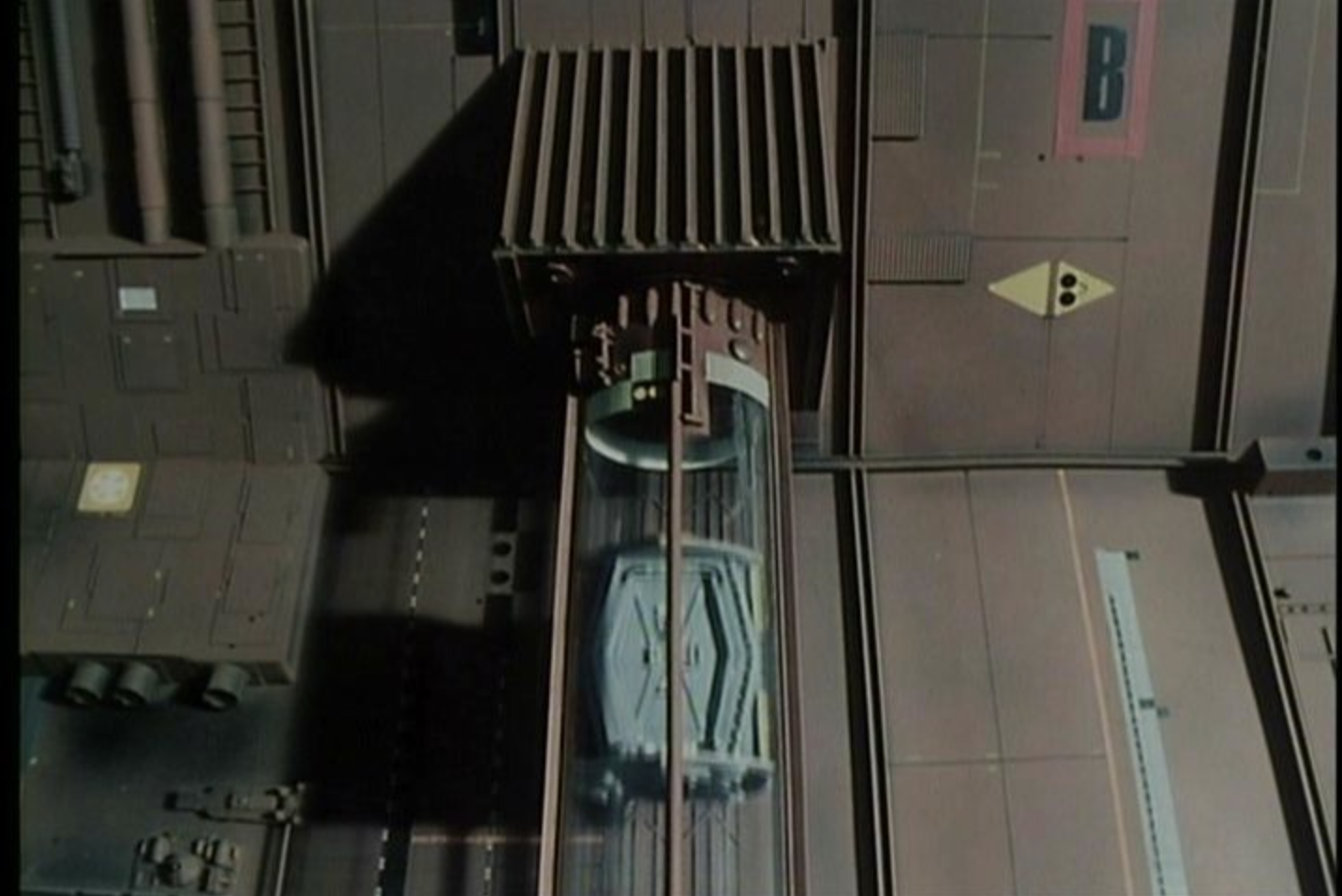

Production took place in the break between the drastically different Season 1 and Season 2 of Space: 1999, using much of the same personnel in front and behind the camera, as well as much of the same visual style. Designer Reg Hill recycled sets from Space: 1999 to form the interiors of the Altares.

The main personnel change was the composer Derek Wadsworth, better known at the time primarily for his work as musical director and session musician, as for the musical Hair and for Dusty Springfield. However, Wadsworth had been making ventures into the world of score since the early 1970s, and would later help score David Bowie’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). Early 70s plans to create a puppet popstar had first brought him into contact with Anderson, who asked him to create the score for The Day After Tomorrow. And what a score it is: standing shoulder to shoulder with the best of Anderson’s other collaborator Barry Gray, it has a sense of grandeur, melancholy, and groove perfectly fitting both the existential and psychedelic aspects of the production.

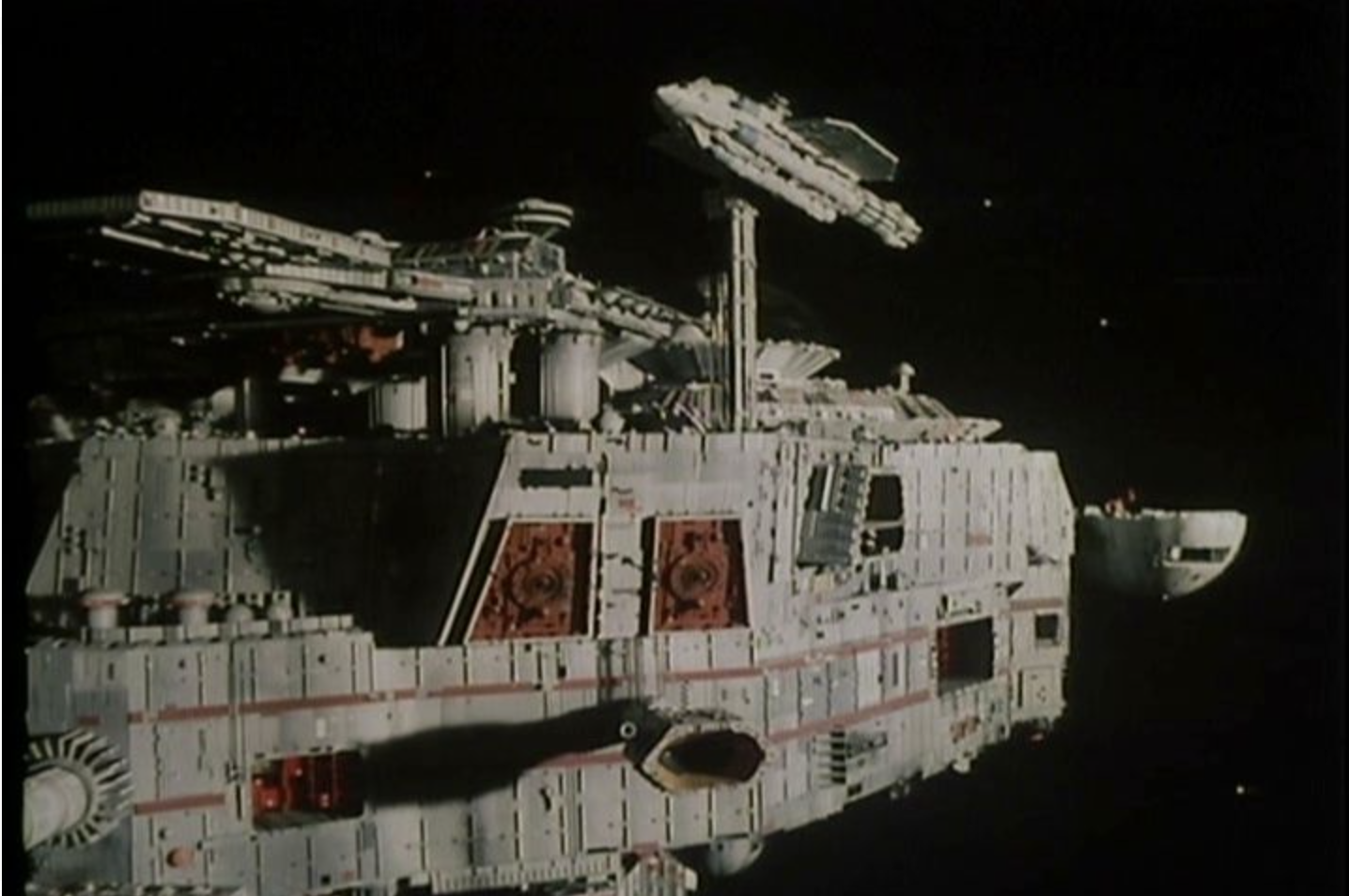

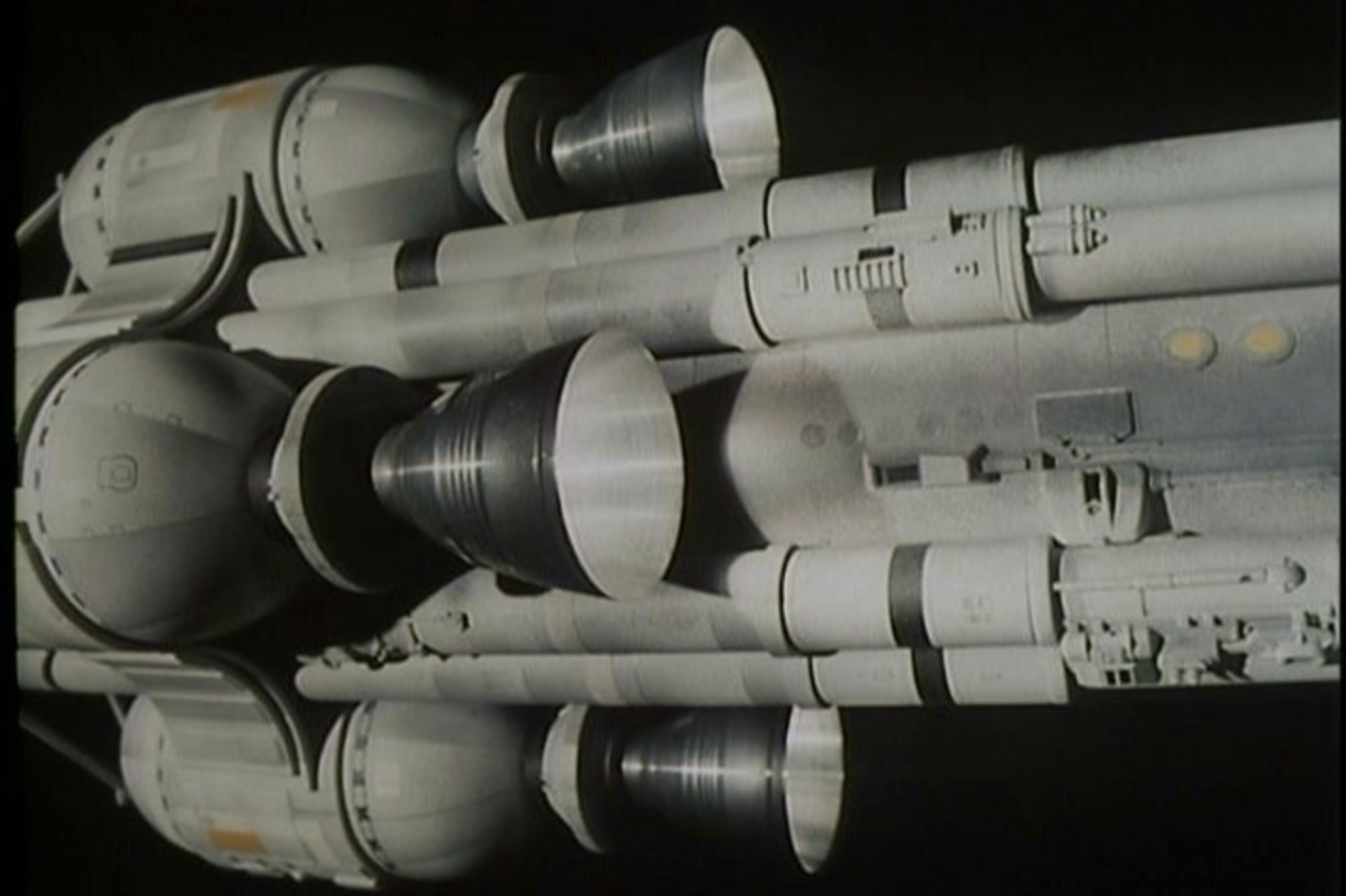

Brian Johnson and Nick Allder’s effects included the use of freon gas to simulate rockets fired in space, later used in Space: 1999 Season 2, and the space warp effect which would also appear in that series. Space station Delta was cannibalized from Space: 1999’s spaceship Daria, and was then reused as part of season two’s moonbase alpha. Pilot control panels were recycled from Space: 1999’s Voyager, the computer panels make a reappearance with their original labels in the second season’s command center, and Nick Tate’s firesuit (made proudly in Slough) reappears on Alphan firemen.

The film’s budget was £120,000. Byrne’s script was dated 27th June 1975, amended on 3rd of July, and began filming at Pinewood Studios on the 21st of July.

Premiering on 9th December 1975 in the US, and on the BBC (unusually for Anderson series at the time) on December 11th, before being repeated in December 1977, it seems to have become an oddly Christmassy program (not the least in that it was reshown in the UK in November 2014).

Time Dilation and Doppler Shift

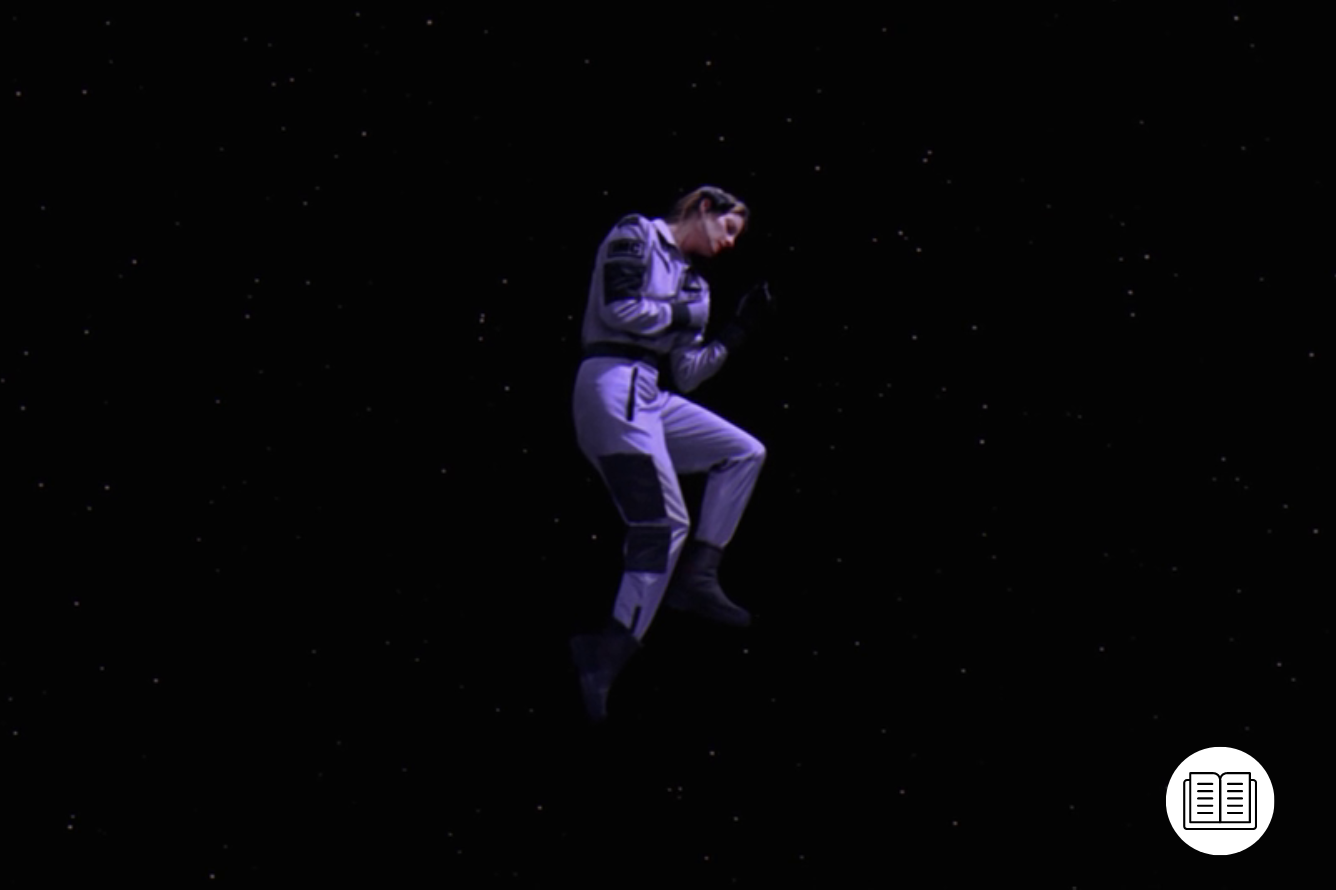

The show does bear many similarities to other Gerry Anderson properties, from the exciting opening montage to the ship going wildly out of control multiple times in the episode, but at others is startlingly unusual: there is no one called Alan in the production, for starters. The human cast receive much warmer treatment than in other live-action productions such as UFO, where the cast were, in their own words, directed somewhat like puppets. The opening sequence ends by showing Jane in distress: our emotional engagement before the story begins is prioritized over our excitement at the effects.

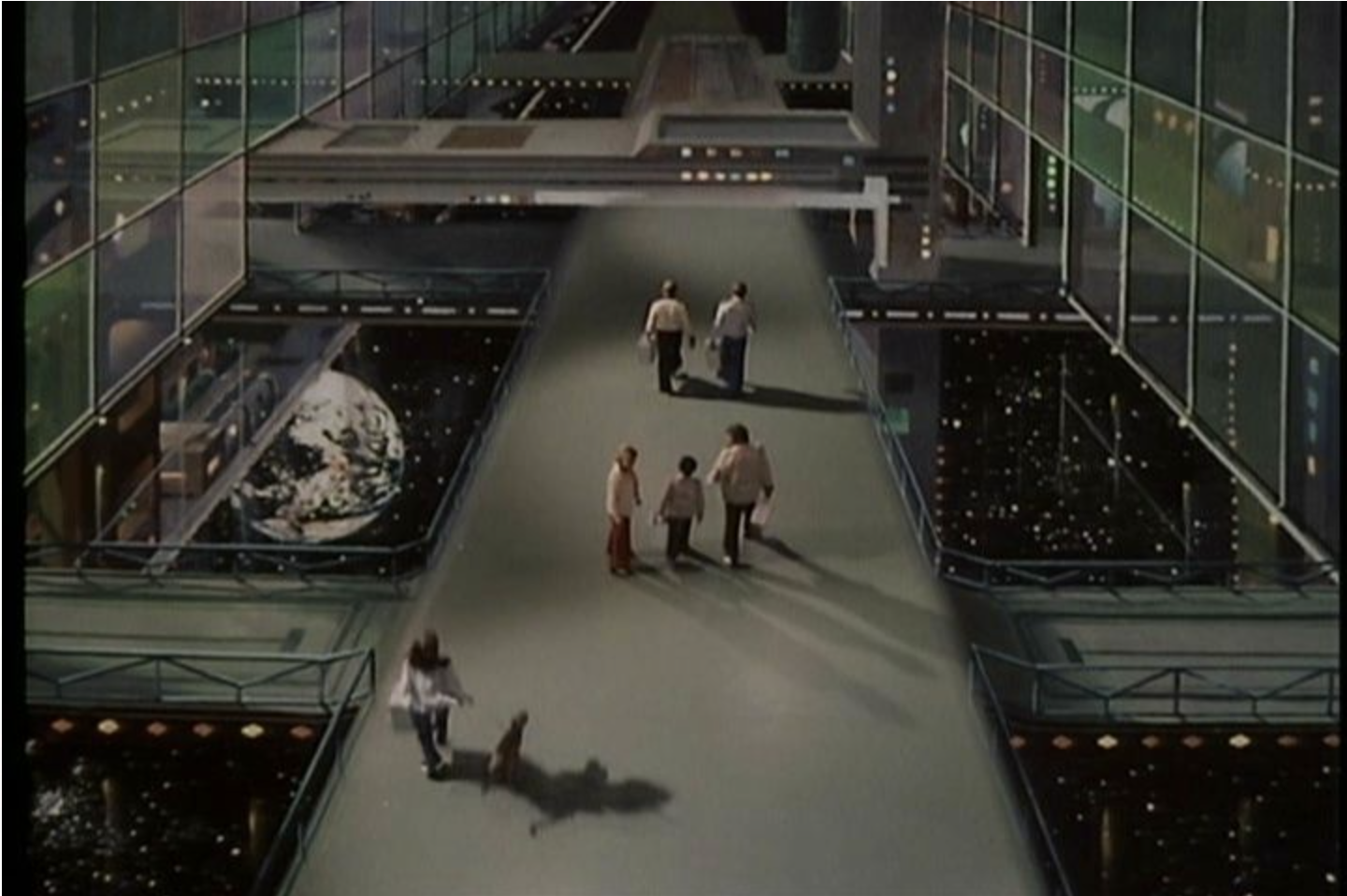

We see the whole trajectory of the mission, from ‘space station delta: the jumping off point for humanity’s first momentous journey to the stars’, to their eventual arrival in a new universe. Science is also foregrounded, as Ed Bishop’s narrator lists actual scientific facts about how photons could work in the ship, and that these could “create the effects suggested by Einstein’s theory of relativity… effects which no man has yet experienced and you will share it… the first to share man’s dream to step outside our planet… orbiting a small cool star we call the Sun.”