The world of Frank Herbert's Dune isn't like most spacefaring sci-fi: There are no aliens, just humans of various stages of mutation (thanks to the transformative effects of the Spice Melange). There's no warp speed: you tuck your spaceship into a big, tube-shaped vessel called a Guild Heighliner and sit inside while it folds space to take you where you want to go. There are no robots or complex computers; humanity outlaws them millennia ago when robots rose up and tried to take over, so people have just trained themselves to do the computing in their brains. Swords have replaced lasers as the primary mode of combat.

There’s an air of the Middle Ages to Herbert’s retrofuturistic realm, interstellar federations replaced by a feudal system that structures itself around squabbling Great Houses and imperial fiefdoms. That blend between the ancient and the futuristic is probably best encapsulated by one of Dune’s most iconic pieces of technology: The ornithopter.

What the X-Wing is to Star Wars, the ornithopter (or ‘thopter for short) is to Dune: small, nimble aircraft used to travel from one place to another on the titular desert planet, or in rare moments, engage in air-to-air (or air-to-ground) combat with the characters’ various foes. It’s the setting for many of Dune’s most iconic set pieces, notably Duke Leto’s trip out to the Spice fields with Dr. Kynes — which introduces Paul (and readers) to the immense power of the Sandworm.

The ‘thopter, of course, recalls many of man’s early attempts at flight; derived from the Greek ornithos (bird) and pteron (wing), the ornithopter is essentially a machine that attempts to emulate the flapping motion of a bird’s wings to simulate the same sense of flight. While it never really found practical purchase in the real world, experiments with the ornithopter date all the way back to the 11th century. Leonardo da Vinci famously studied the flight of birds in order to consider how technology might ape those movements and give man the power of flight. His elegant, sophisticated ornithopter designs were impractical, but decidedly imaginative, and informed centuries of subsequent attempts until the Wright Brothers achieved the first sustained flight in human history in 1903.

In Herbert’s Dune, the dream of the ‘thopter is alive and well, and its combination of futuristic technology and the flapping-wing design lit up the imaginations of readers for decades. In the book, he describes the ornithopter as a jet-assisted aircraft featuring fully-articulated wings that could retract and spread as needed for assisted takeoffs and landings, as well as incredibly agile maneuvers even in the deep deserts of Arrakis.

The “Terminology of the Imperium” appendix at the back of the first book describes them thusly:

ORNITHOTER: (commonly: 'thopter) any aircraft capable of sustained wing-beat flight in the manner of birds. - Frank Herbert, Dune (1965)

But where da Vinci thought of birds, Herbert thought of bugs: the ‘thopters “[hum] softly on standby like a somnolent insect.” To dive, the ‘thopter folds its wings against its sides, “snicked in to beetle stubs.” Also, unlike traditional ornithopter designs, it doesn’t rely solely on the wingflaps to achieve flight; Herbert’s ‘thopters are equipped with jet pods that control thrust, with the wingflaps mostly providing elevation, pitch, yaw, and roll.

It’s an incredibly unique and different approach to sci-fi aircraft, blending the organic with the futuristic in a way that befits the strange, mystically analog world of Herbert’s worlds.

Like so many things about Dune, adapting the ‘thopters to other media has led to some fascinating interpretations of the craft’s design. From films (both abortive and realized) to television to computer games and beyond, the ornithopter has had quite a few iterations over the years. And with 2021’s version, the ornithopters have never looked better.

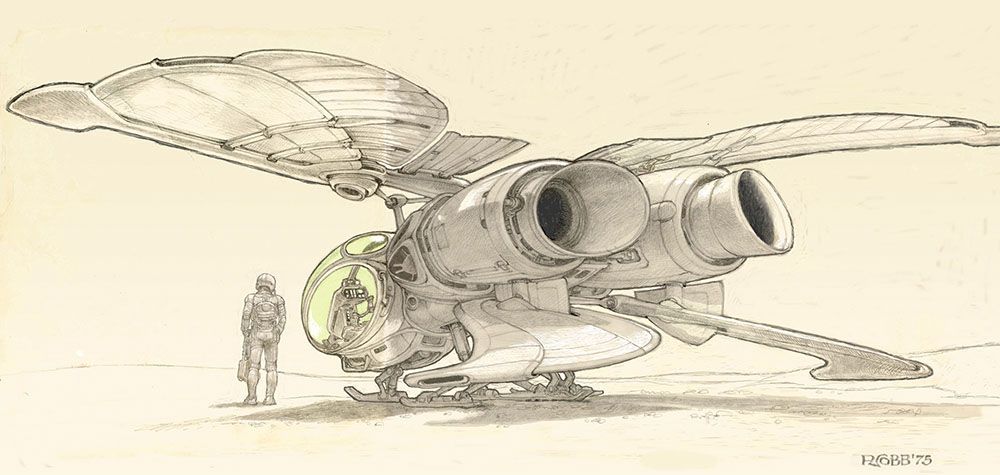

Jodorowsky’s Dune (1975): What Might Have Been

The first attempts to bring ‘thopters to the screen came courtesy of Alejandro Jodorowsky, whose abortive film version of Dune in the ‘70s gave concept artists like Ron Cobb ample runway to envision the kinds of buglike ‘thopters his wild take on the material would allow. Other designs made for more hawk-like profiles, befitting the bird at the center of the Atreides crest. But as imaginative as these designs would be, we’ll never know how they would have panned out on screen — especially given the resources and special-effects capabilities of the time.

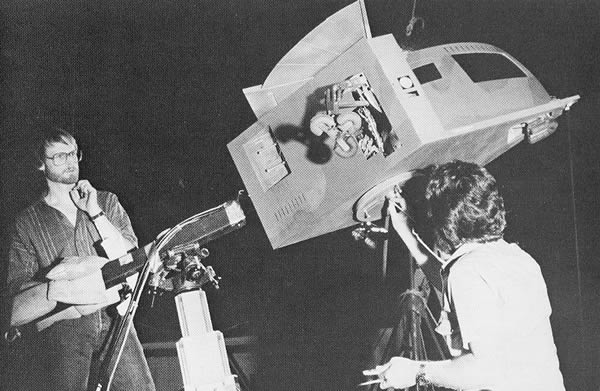

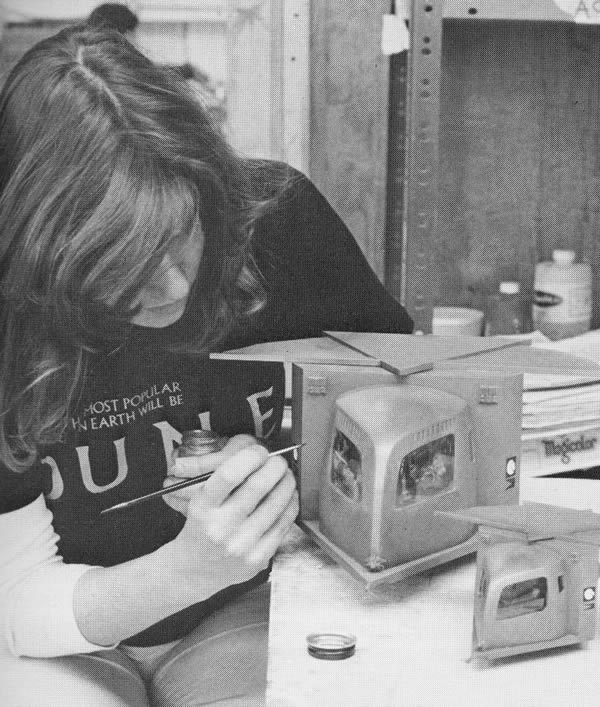

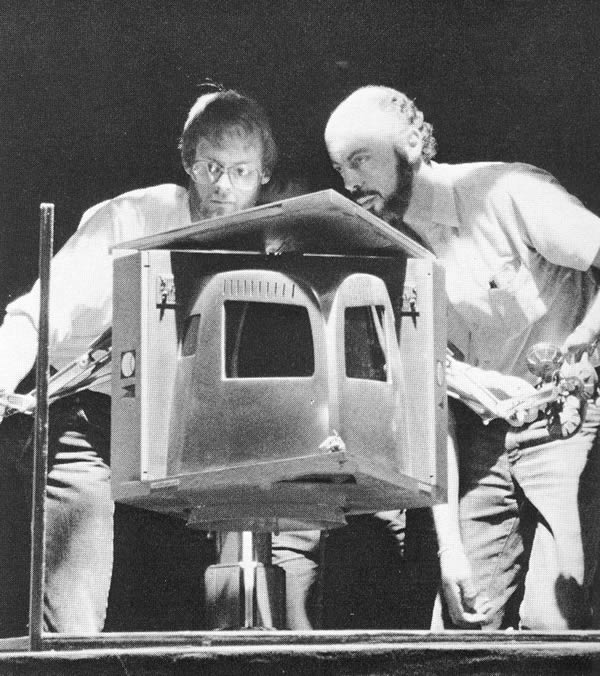

1984’s Dune: The Boxy Boy

David Lynch’s 1984 version was a visual wonder, with Italian-inspired interiors folding into organic, HR Giger-designed stillsuits and all manner of off-the-wall interpretations of the material. But his take on the ornithopter is one of the few places in which the look of his Dune falls short. Essentially, the Atreides ‘thopter we get to see on screen for the aforementioned spice tour looks like a cramped, golden, diamond-shaped room, with two small, static wings sticking out the side.

It’s hardly cinematic, and its few short moments seen in flight are some of the weakest SFX shots in the film. (The same can be said of the other spacecraft work; methinks Lynch’s effects budget just reached its edge when it came to the flying bits.) The Harkonnen ‘thopters fare slightly better, with a double-hulled design not dissimilar to the P-38 Lightning fighter plane used frequently in World War II. But still, where are the flapping wings?

Overall, Lynch’s version of the story didn’t have much time for ‘thopters, at least on the part of the Atreides: the Harkonnen ‘thopters get way more to do, from bombing Arrakeen to providing Paul and Jessica with their much-needed escape. Even so, their presentation in the film is too stiff and boilerplate to fit the rest of the weirdness Lynch’s take had to offer. They may as well be X-Wings.

The Dune Videogames (1992 - 2001)

While the Lynch film was a flop, its legacy lived on for a time in the computer games that spun off from its telling of the tale — each of them with their own takes on the ornithopter. The 1992 adventure game featured ‘thopters that bridged the gap between the Lynch version and Herbert’s, with an Apache helicopter-style cockpit, retracting wings that shifted forward on takeoff and buglike legs for landing.

Then there was Westwood Studios’ Dune II: Battle for Arrakis (1992), which is often credited as one of the first real-time strategy games ever made (Westwood would go on to refine the formula in the Command and Conquer series). Here, the House Atreides’ ornithopters are sleek, silver, hawk-like fighter jets whose wings flap like a bird’s, their silver frames contrasting against the tan desert.

Dune II would be remastered in 1998 as, well, Dune 2000, with the ‘thopters being upgraded even more with a helicopter-like body and brown paint scheme, but with those same birdlike wings sitting atop the frame as opposed to along the sides.

In that game’s sequel, Emperor: Battle for Dune (2001), the ‘thopters would get upgraded once again, this time leaning even more into the P-38 Lightning look for the Atreides, a double-hulled craft connected by a spoiler in the back and side wings that maintained that bird-like wing motion.

Generally, the games were given a lot more latitude to experiment with the looks of the ‘thopters, and it’s neat to see how many dramatically different approaches each version took. Whether flitting between insect or bird, fighter jet or shuttlecraft, the Dune games have been a fascinating what-if for designers to try a number of approaches to the ships.

Frank Herbert’s Dune (2000): The Harrier

The next major on-screen attempt to get the ornithopter right was in the Sci-Fi Channel miniseries version of Dune from 2000, which…. Also had some difficulty nailing the whole ‘flapping wings’ component of the iconic craft. To their credit, they leaned wonderfully into the ‘bug’ attributes of Herbert’s descriptions: its squat frame and tiny, jointed legs (as well as the buzzing, cicada-like sound design of its flight) certainly calls to mind desert beetles.

But I ask again, with all the impotent fury of George Costanza, where’s the flapping?! Rather than the beating wings of its forebears, John Harrison’s version instead opts for a pair of adjustable rear wings atop the cockpit, with jump jets embedded in the middle of them. Presumably, the technology just wasn’t there (especially for a modestly-budgeted basic cable miniseries) to render realistic-looking wing flapping in CG, so they went with more of a VTOL approach. Still, for all the relative agility the design renders — Paul and Jessica’s chase through the desert valleys to evade Harkonnen patrols in Part I is particularly exciting — it still doesn’t scratch that itch for a real ‘thopter.

Dune Part One (2021): The Dragonfly

This is more like it. Denis Villeneuve’s version of the ‘thopter not only gets plenty of screentime to merit its status as one of Dune’s most recognizable craft, but it’s also as close to a perfect blend of Herbert’s outlandish lore and the familiarity of military designs as you could possibly get.

This time around, we’ve got a design that echoes the angular, but chunky aesthetic of modern helicopters and aircraft, while incorporating the flapping bug-wing mechanic in ways that feel realistic and grounded. These ‘thopters look more like dragonflies than beetles, their thin frame accented by two pairs of slender, fully-articulated wings that flap in rapid succession to simulate the hummingbird-fast movement of insect wings.

They somehow look even better parked, the eight wings tucked in against the elongated hull when the craft is at rest. In scenes surrounding the landed ‘thopters, the desert sun beating heatwaves against the ship’s strong profile makes you feel like you’re watching the opening scene from Top Gun.

The real magic of Villeneuve’s bug-boys, though, is in their ability to connect us to the stranger elements of the Dune-iverse. They read as recognizable aircraft at a glance, but their dragonfly wings offer something new and inviting (and, it must be said, innately cinematic) for the casual viewer to behold. So much of Villeneuve’s other designs are mad bursts of brutalist architecture mixed with rococo curves, from the featureless maze of Arrakeen to the Fleshlight-on-shrooms look of the Guild Heighliners.

But take one look at the ‘thopter, and you get an immediate feel for how it works. You climb into the cockpit with the characters and watch them flick manual switches, operate joysticks, strap into seats. When the craft dives, its four wings retract and hug the hull of the ship; when one breaks off in a sandstorm, you instantly intuit what that will do to the aircraft.

What’s more, we get subtly different iterations on the ‘thopter design at various points in the story. The Atreides ‘thopters feel chunkier, more militaristic, freshly delivered to Arrakis (or at least borrowed from the Harkonnens). But later on, when Dr. Kynes escorts Paul and Jessica to a new ‘thopter to help them escape the Harkonnens after their escape, you can see it’s an older, civilian model with a rounded cockpit and a stubbier tail. They no longer have the resources of a Great House — they’re making do with what they’ve got.

Not only does this version of Dune play with aesthetic differences between factions in its designs, but it also takes care to build a history for the planet that extends beyond the events of the film. The ‘thopter just becomes a visually legible means of doing so.

Did They Finally Get the Ornithopter Right?

While I’ve still got my issues with Villeneuve’s Dune — ones that seem mostly relegated to his take’s inescapable need for a Part Two, which thankfully seems likely — the ornithopter is one thing his vast, expansive take gets right.

Amongst the nearly magical world of prescient messiahs, human computers, and skyscraper-huge sandworms, the ornithopter represents one of the most tangible, accessible elements of one of science fiction’s strangest universes. And I’m so glad that we finally got the ornithopter fans deserve.

This article was first published on October 24th, 2o21, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂