Frank Herbert wrote the original Dune novel in 1965 and almost immediately people started trying to adapt it for the screen. Alejandro Jodorowsky spent millions not making it and many others came and went before David Lynch made his 1984 flop.

Then, in 1999, cable network the Sci-Fi Channel decided to spend $20 million turning the first book in Herbert’s series into a miniseries, an ambitious undertaking watched eagerly by the novel’s rabid fans and those who considered the author’s work unfilmable.

Twenty-one years on, we spoke to several cast and crew to find out how both Frank Herbert’s Dune (2000) and Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune (2003) came together. In this first installment, we concentrate on Dune.

As Told By

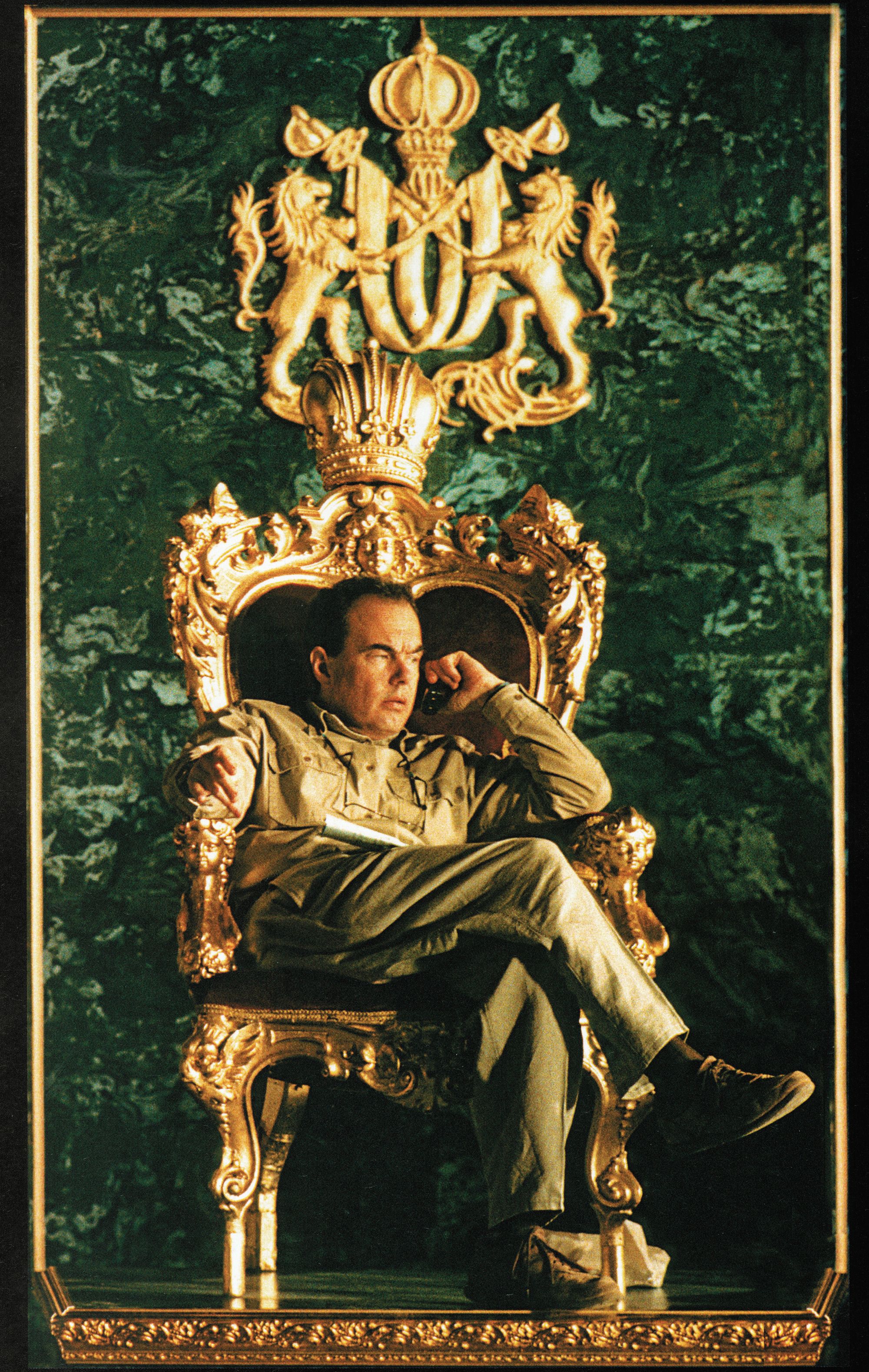

- John Harrison (writer and director)

- Harry B. Miller (editor and associate producer)

- Greg Yaitanes (director; Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune)

- Alec Newman (actor; Paul Atreides)

- Julie Cox (actress; Princess Irulan)

- Ernest Farino (Visual FX supervisor and 2nd unit director)

John Harrison (writer and director): I have enormous admiration for Lynch as a director, but I don’t think that project turned out the way he wanted. It had such incredibly beautiful imagery, but the adaptation of Herbert’s story left a lot to be desired as far as a fan like me was concerned.

Harry B. Miller (editor and associate producer): Dune has a lot of baggage, a lot of pre-conceptions. A lot of the criticism I would read online [about ours], was, ‘They didn’t have the black outfits and it didn’t rain as it did in the David Lynch version’ – no, of course, it didn’t! Because David Lynch did a terrible job, it was an awful movie. It’s iconic, but it’s bad!

Greg Yaitanes (director; Children of Dune): I had lunch with Sting once and I wanted to talk about Dune, but he wouldn’t talk about Dune… it must have been quite an experience.

Alec Newman (actor; Paul Atreides): One of the problems with David Lynch directing, it’s like a double negative effect. David Lynch, who is a visionary and slightly leftfield, directing a version of Frank Herbert’s Dune [novel], which is visionary and slightly leftfield, it got TOO confusing. I haven’t seen the three-and-a-half-hour version though. We had the time on-screen to tell this story in a way that would avoid what happened with the David Lynch version.

Starting Work on Frank Herbert’s Dune

Despite the endless never-realized attempts by Alejandro Jodorowsky and directors like Ridley Scott to bring it to the screen as well as Lynch’s noble failure, there were always people who wanted to see it done properly as a movie. Former George Romero collaborator Richard P. Rubinstein picked up the screen rights to Herbert’s novels in 1996.

John Harrison: I knew [exec producer] Richard Rubinstein really well. He called me up and said, ‘I’ve got the rights to this sci-fi novel, I don’t know if you’ve ever read it, called Dune.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’ve read it.’ (laughs) He thought I might be interested in pitching it. Of course, I jumped at the chance.

Harry B. Miller: I re-read the first Dune book and I was like, how are they going to do this?

John Harrison: I thought, we’re doing this for television, we’re not trying to compete with David’s film, let’s just try to do something really unique and tackle the story in a way it hasn’t before. I knew doing the project as a miniseries, I was going to have a great deal more time to tell the story than David had.

Fortunately for me, Herbert made it easy to pitch – the book really gives us the guidelines for how to do this. There are three books in that first book. There’s a section about Dune, a section about Muad’Dib, and a section about the prophet. I pitched it that way.

The Sci-Fi Channel agree and three two-hour movies were greenlit. Thoughts turned to how they would build the world of the show, and casting began in earnest.

John Harrison: I knew I was going to do a lot of casting out of the UK, but we had been really looking for Paul. I spent a lot of time interviewing actors in LA and then New York. The further east I went, the better the actors got. I came to London to do a casting session and was particularly interested in meeting an actor I’d seen before and thought might be really good. But the casting director said, ‘Listen, there’s this one actor I really want you to see. He’s doing a play with Cate Blanchett and I’m having difficulty organizing his schedule, but if you can hang around for another day, I can get him in the evening.’

Alec Newman: I was in bed with flu and I got this call to go and see John Harrison. I was feeling awful! I was feeling so wretched that I said to my girlfriend at the time, ‘I don’t really want to go’ and she said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous, look at what this thing is.’

John Harrison: He tried to back out of the meeting because he had the flu.

Alec Newman: I met John at the Cadogan Hotel just off Sloane Square. I auditioned for Paul in John’s room, basically. They set up a camera. I don’t think he was seeing a long list of actors. We did a little session and he gave me notes.

John Harrison: He was pretty low energy, but there was something about him that I really liked. I gave him the speech that Paul delivers on top of the Muad’Dib statue. He said, ‘How do you want me to play this?’ I said, ‘You’ve got to grow through the speech, [and] become more and more impassioned. Maybe think of Hitler talking to the crowds in Munich.’ I got back to Prague, called the producers, and said, ‘I think we got the guy.’

Julie Cox (actress; Princess Irulan): I had read the book. I knew her voice, [and] understood what the job of bringing her to life was. I was so excited to be offered that part.

John Harrison: Richard Rubinstein felt that to gain credibility and really put people’s minds at ease, a name above the title would be great. He found out that William Hurt (Duke Leto Atreides) was a fan of the book, so he reached out. William has family in Europe and he spends a lot of time there, so it was great for him. He didn’t have to commit to the entire six-month production because he was only in the first night.

Alec Newman: William has a kind of mystique about him. I was pretty awestruck to be working with someone of that caliber, but what was nice to find out later was William was freaked out to be arriving in the middle of the production because we’d already got going, we’d been shooting for a few weeks. He was quite reticent coming into something that was off and rolling.

Harry B. Miller: [During filming] we were staying in this place called The Blue Key Hotel. William Hurt had a room there as well. I saw him in the hallway one day and started chatting with him… I was such a fan of William Hurt, I was so impressed that we got him. And he asked me, ‘So what do you think of my performance? Do you think it’s a little slow?’

And I said, ‘Well, honestly, yes.’ He had taken this point of view that his character was so regal and so pondering that he took forever to deliver his dialogue. He would take these huge pauses. He can’t get mad at me now. I literally had to speed up the space between line deliveries and he didn’t notice. But it all worked out – he was terrific and he took my suggestion without killing me.

The Sets and Locations of Frank Herbert’s Dune

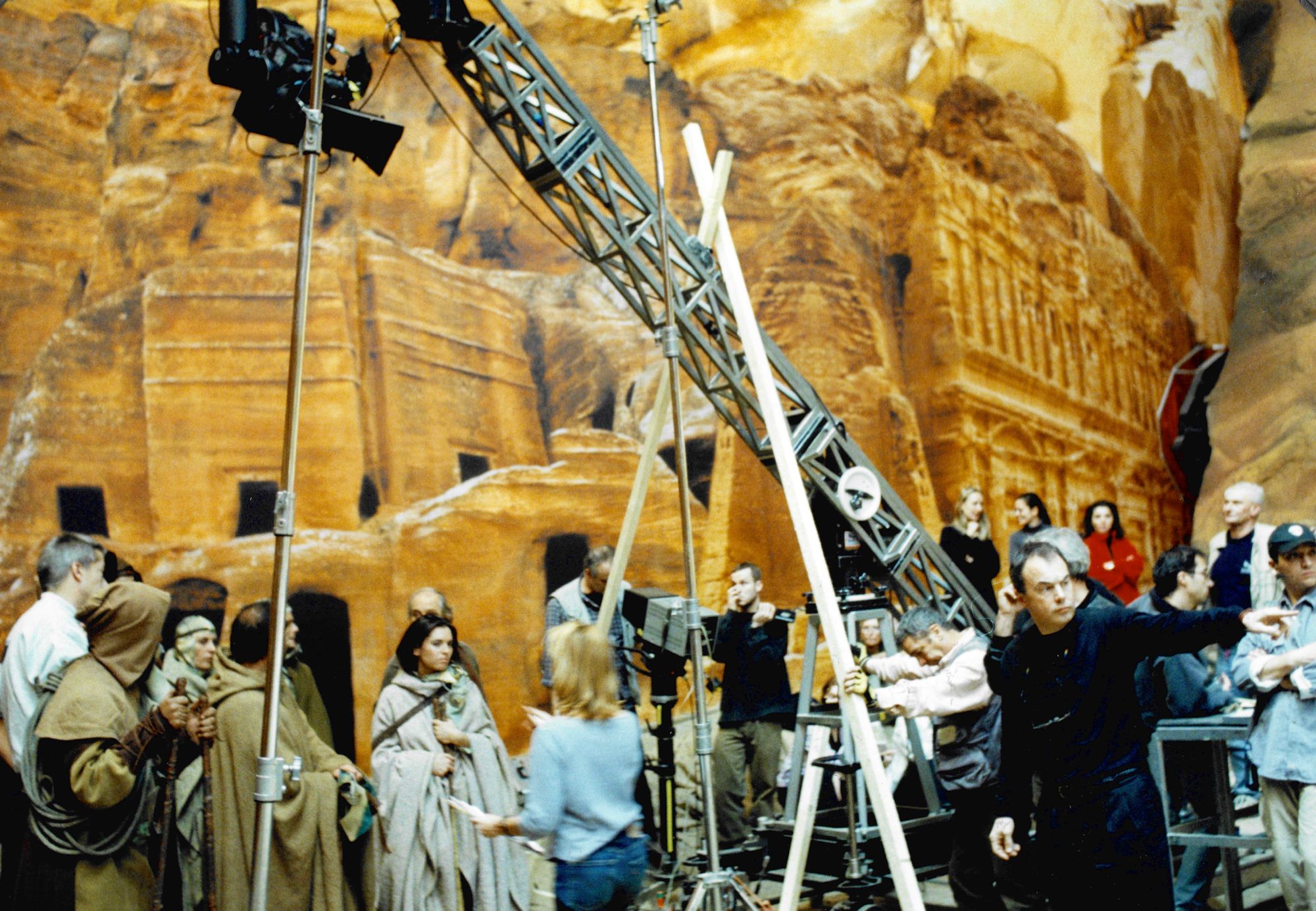

Locations were scouted in Morocco, but it proved to be too complicated and expensive. Instead, the decision was made to shoot entirely on soundstages at Barrandov Studios in Prague, where they built huge sets and on which Oscar-winning cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, Reds) used a unique technology called Translights to recreate epic alien worlds like Arrakis.

John Harrison: Everybody loved this material. Vittorio had an encounter with Dune in the early days when Jodorowsky was trying to do it and then Ridley Scott. Never came off, but when my assistant director, who was doing another film with him, mentioned to him that I was doing Dune, he dropped his fork over lunch and said ‘I want to meet John’. He almost pitched me. We went to Chateau Marmont, I was in his suite and he was like, ‘Now John, I think I can really do this great for you.’ I was like, ‘Okay Vittorio!’

Alec Newman: A Translight is a huge, physical backdrop.

John Harrison: Vittorio said he was experimenting with this process that could really work. Vittorio and his son would find photos of the Gobi or the Sahara and he would merge them on the computer. And he would light them on the computer. He had total control over that. We did several other backdrops for the imperial palace. He would take imagery from old castles [in] Europe and the astronomical clock in the tower of Prague. He would paste them together so they became something entirely new. He would send that imagery off to this company that would print that onto these massive backdrops. And they were huge – they were 300ft long by 100ft tall.

Ernest Farino (Visual FX supervisor and 2nd unit director): They literally hung these giant canvases around three of the four walls of the studio.

Julie Cox: They were amazing as an actor to work with because you’re always looking at a background.

John Harrison: They had to be created by this special company in Italy. They would send them in in these massive rolls that looked like carpets for some giant’s castle in the sky.

Ernest Farino: In the corner of the studio, where the TransLight wrapped around in a curved way, the perspective got very distorted. It was always a trip to try and find a different view, a different angle on those Translights and to try and avoid that twilight zone of the corner of the stage.

Julie Cox: We were shooting space in Prague. It’s about as surreal and bonkers as it gets. I don’t think it dawned on me what we were doing until I turned up on set the first day. Because those sets were huge. It was like, this is why I wanted to be an actor. Walking into the soundstage full of sand imported from Morocco, I think.

Alec Newman: They must have been bringing in trucks of sand. They were building these huge, double-story sets. The set for the main room in the Arrakian palace was huge and it was real and there were bits of it that were complete that were never filmed.

Julie Cox: Vittorio had wanted to be doing Dune with Ridley Scott at one point. He came to work with a bible of designs and sketches and that was, like, wow! This wasn’t just another job. This was a dream realized for quite a few people.

Filming Frank Herbert’s Dune

Filming on the miniseries began, as the rest of the cast and crew descended on Prague.

John Harrison: To the producers’ credit, they were like, ‘Look, we got $20 million to do three movies. What we got is what we got.’ But they never challenged me creatively to say, ‘Aren’t you thinking too ambitiously?’ They gave us limits and we had to stick to them, but my creative imagination never felt completely hampered by that.

Alec Newman: I had to get on with the physical parts of it straight away. The fight training was with a guy called Petr Drozda who used to be an Olympic wrestler for the Czech Republic or Czechoslovakia. That was proper boot camp with these fantastic stunt guys.

I remember drinking coffee and eating meals wading through the Qur’an because I did talk to John about the idea of one man’s hero is another man’s terrorist. This was a man who sides with people of the desert, who take down what is the empire, basically. We thought a lot about this idea – that this guy from another angle might be the villain of the piece.

Julie Cox: The costume designer had done Amadeus and the costumes were incredible, but there was one scene, it may be the first time you meet [my character], she’s wearing a butterfly dress. And the butterflies are real. They were cocooned and they were waiting for them to hatch in a room somewhere, to go, ‘Alright, we’re good to go.’

Unfortunately, a lot of them didn’t make it because they flew into the lights. These beautiful butterflies they collected from everywhere. It was horrific. These poor things, being killed, like those lights you get in takeaways – bzzzzt.

Ernest Farino: On Dune, I directed 2nd unit. There’s probably about a full hour of the miniseries that is entirely mine. On the first day, the Czech camera assistant put the name of the director on the slate and he misspelled my name. He put E. Farno. I sat down and wrote this biography of a fictional director who’s been ignored in the history of film. It just became this elaborate joke. Every time I call up Harry Miller or John Harrison, John especially answers the phone, ‘E. Farno!’

Harry B Miller: The first one was shot on Super 16mm – Vittorio Storaro, that was his deal, he wanted to shoot everything on film. We had some technical issues with it though. The actual cameras, the frame isn’t steady like a 35mm or 70mm camera, there’s a lot more weave and movement, so it creates some issues with visual effects.

Ernest Farino: We probably had three or four [FX] companies on the show, the principal one was Area 51 which I’d used previously on From the Earth to the Moon. [They] did the Sandworm stuff. Because of local laws in Prague, we could not have firing weapons. So all the weapons that the Fremen and the Harkonnen use, we had to animate the muzzle flashes.

Alec Newman: There are some really quite entertaining outtakes. I still have a videotape. And invariably they’re John off-camera going, ‘There’s a worm rearing up and you’re really scared!’ and me laughing because I can’t hold it together.

Harry B Miller: I was in Prague for the first one, I don’t speak any Czech and our film lab was in Rome. They had never done a production in the American format of NTSC, so our dailies for weeks kept coming in incorrectly.

Ernest Farino: One of the dilemmas we encountered was how do we do the blue eyes? I recalled reading how back on the first Superman movie, the costumes that Marlon Brando and Susannah York wore on Krypton were made of front projection material, so you would have a mirror in front of the camera and just shine white light and it gave the costumes this glowing bright white effect. In one of our Dune meetings, I suggested whether there was some way to put some kind of coating on contact lenses.

Vittorio picked up on this right away and they actually hired an optometrist to make contact lenses that had some kind of coating. So basically the actors are wearing these contact lenses which reflected this blue light that was off-camera.

Some of the Frank Herbert fans got all bent out of shape because the eyes are described as having a dark blue iris and a lighter blue around it. I was like, well, aside from injecting blue dye into the eyes of the actors, there’s a certain limit to what you can accomplish!

Looking back at Frank Herbert’s Dune

Unlike Lynch’s version, the miniseries made it possible for people who hadn’t read the book to understand and enjoy the story.

John Harrison: It’s not a hardware movie. Yes, there’s plenty of stuff about space travel, but it really is not a heavy hardware sci-fi saga. It’s more of a human saga, it’s much more about massive power struggles among imperial houses. It’s much more Elizabethan or even medieval than it is hard sci-fi. So that’s the tone I went for. The sci-fi is there, but it’s almost taken for granted. I’m not saying to the audience, let’s explore this new technology.

Harry B Miller: The great thing about the two miniseries is they were much more complete than any of the films could be because we had a six-hour running time. There was one scene in particular where Muad’Dib was addressing the Fremen and there was a big crowd and I couldn’t wrap my head around what the tone was, the intent. Fortunately, we were all in Prague and I could drive to the set. Or we both lived in the same hotel, we could have dinner and I could ask those questions.

John Harrison: One of the first choices I made with this adaptation was to abandon the thing that David did, which I didn’t think was very successful. The book has a lot of internal monologues… you really get into their hearts and minds and souls. There are long passages that are just them internally talking about what’s going on. I decided not to do any of that. No voiceover narration. I externalized all of that.

Two decades later, the cast remembers it being a magical time in their careers.

Alec Newman: I had all the bluster of any 25-year-old and when I think back to the experience now, it was an amazing time in my life. It was a bit of a mad dream, which is not a million miles away from that book.

Julie Cox: It was amazing and it was pre-social media. We were living there for about six months. Everyone hung out together. I’ve still got friends from Prague from that job.

Alec Newman: We had a very good time. It was definitely ‘work hard and play hard’ as far as I was concerned. Of course, there was that vibe. I was sitting in my hotel room at half-past eleven one night and Jimmy Watson, who played Duncan Idaho, a fellow Glaswegian, basically phoned me up and got me out of my bed to go for a drink because it was a weekend and we weren’t working. It was early in the shoot and I was being very diligent.

Julie Cox: [It was] exactly what it means to be an actor. Don’t take yourself too seriously, get dressed up, be true to your job, [and] be committed, but also enjoy yourself. Everyone totally respected the ambition of what we were doing, but we had such a good time making it. I haven’t really experienced anything like that since on a job.

Alec Newman: Julie Cox, PH Moriarty (Gurney Halleck), Saskia Reeves (Lady Jessica), we’re all still in touch. But even if we’re not in touch, when we do speak we pick up where we left off, because it was such a memorable, vivid experience on-set and off.

Frank Herbert’s Dune was broadcast on 3 December 2000 in the United States and became an instant success, both critically and commercially. It won two Emmys, for visual effects and cinematography.

Ernest Farino: The Dune miniseries had the highest rating at that time in the history of the Sci-Fi Channel.

John Harrison: The Herbert family loved them. That by itself made me feel great. They told me that Frank would have really liked this adaptation.

Ernest Farino: It was fun to go to the Emmy ceremony. The Emmy that is handed to you, they take it back. Because they don’t want to have backstage a thousand Emmy statues taking up all that space. So basically they’re handing out the same physical statue to everybody. They said, ‘okay, we’ll take it back’ and I’m, ‘like hell you will’. You go downstairs and there’s a huge ballroom [with] table after table of Emmy statues. They’re basically handing out the same statue any time anybody wins.

Now, with Denis Villeneuve finally bringing a new version of the book to the screen, what is the legacy of the miniseries?

Alec Newman: It was so weird to drive down Sunset Boulevard and see a billboard with your head on it.

Harry B. Miller: I can only deal with the material that’s handed to me. Fortunately, John has the brains and talent to pull it off. We were trying to do something that was faithful to the Frank Herbert text and I think we did a great job of it.

John Harrison: I’m involved in the new one tangentially and I’m really excited about it. Mine is still there, it is what it is. I was very lucky because of the creative team I had around me.

Alec Newman: It’s finally being revisited and it’s way, way overdue. But it’s a compliment to how brilliant the story is that it’s taken this long for someone else to figure out how to do it.

Julie Cox: There are people that still send me letters and stuff. I just can’t believe it’s been 20 years.

This article was first published on September 21st, 2021, on the original Companion website.