In the introduction to a 1986 illustrated book published as promotional material for the 23rd season of Doctor Who, then-producer John Nathan-Turner writes.

“It used to be claimed that there were just two requirements to be a ‘companion’ in Doctor Who, the world’s longest-running science-fiction TV series:

(1) To be able to scream and run at the same time!

(2) To be able to say ‘What do we do next, Doctor?’ with conviction!!”

While Nathan-Turner may be writing this in the past tense, not to mention with a certain tongue-in-cheek tone, this comment represents a core attitude that has framed the companion character in Doctor Who throughout the series’ history, and by extension the treatment of female characters in this series overall. The ‘companion’ character holds a central role in the structure and premise of the show – arguably no less important than the Doctor themselves.

These characters mark the point of identification for the viewer, an audience avatar character that the alien Doctor invites into the adventures of their travels just as the viewer is invited into the adventures of the series. These companion characters are also typically women, and throughout the history of the show, this has, on one hand at least, left room for a potentially progressive assumption. Under this assumption the Doctor, as the title character and (usually) male lead, is not the ‘main’ character of the series – instead, we as viewers see the events of the show through the perspective of a (usually) female protagonist who is, despite not being the title character, more centralized by this format.

However, on the other hand, the archetype of the companion can also be a restrictive space, as for many decades this was the only role that recurring female characters on Doctor Who were made to occupy. This has set normative precedents around the companion’s function and role within the narrative that have continued to have an effect on the structure of the show well into the revived series. In the wake of Jodie Whittaker’s final season as the first female incarnation of the Doctor – a casting decision that carries with it an assumed expansion to the role of women within this show, let us consider the history of the companion archetype. In many ways, the companion has been modernized for a contemporary world of normalized gender equity, but in other ways these characters remain defined by their predecessors, unable to escape the established precedents that come from nearly 60 years of serial storytelling.

Conventions and Formulas in Time and Space

Doctor Who is a series with a fundamental paradox at its center. It demonstrates a commitment to consistent reinvention of its own format, challenging the notion that there are fixed, tangible qualities that make Doctor Who what it is. However, it also demonstrates a habit of falling back on these qualities, often defaulting to narrative or textual structures that are easy, familiar, or nostalgic. As a result of this, the series maintains an intimate link with its own history and internal perception of what qualities make up its own complex textual identity, yet also presents itself as prepared to break these at any moment.

A particularly dramatic example of this occurred as early as the original 1963 season, a period of the show characterized by an initial intention for Doctor Who to be an educational program designed to teach children about science and history. In the serial ‘The Daleks’ (S1, Ep5-11) this educational element was shoved into the background for seven episodes as the show concentrated on developing the precise kind of campy, science fiction monsters that executive producer Sydney Newman had been vocally opposed to any inclusion of. This serial was, of course, famously successful – creating a wave in British culture around the popularity of the Daleks – and this resulted in the show adopting this model as precedent, one that continues to influence the narrative structure of Doctor Who almost 60 years later. This internal dependency upon precedents has come to dictate how the show operates narratively, structurally, and thematically, and in many cases can be seen as a strength for Doctor Who, but it can also be limiting. The narrative structure of the “Bug-Eyed Monster”, as Newman referred to them, has served the series well, but as the show has evolved and begun to more explicitly explore the potential for genre-bending, the overreliance upon monsters can arguably become repetitive and tiresome.

The structure of Doctor Who as a serial narrative thus emphasizes this internal dependency upon precedents, requiring the show to maintain a certain degree of continuity with its own past. While the series has historically demonstrated itself to be more than comfortable engaging in a constant rewriting of its own canon, the series also articulates distinct identities within itself. Doctor Who has put itself through numerous explicit rebranding efforts, codified as new ‘eras’ each with a distinctive look and style as if they were a series of different shows rather than just one long one.

Despite being separated by changes in visual and writing styles (not to mention cast changes), these eras nevertheless connect together in a serial continuity. Doctor Who thus balances a consistent reimagining of its own textual identity while maintaining a relationship to its roots. Certain ‘constants’ develop throughout the series that preserve core dynamics that, for whatever reason, have remained. Some of these rules have of course been broken – the TARDIS has appeared as something other than a police box, the Sonic Screwdriver has been replaced with sunglasses, and monsters have taken on roles as recurring or sympathetic characters (such as Strax or Rusty the Dalek), and the companion has been allowed operate outside their established gender-based role, but these deviations from the norm have almost always been presented with an implicit expectation that they will eventually be returned to ‘normal’.

When these expansions on the Doctor Who formula are changed back, this only serves to reinforce the established precedents as elements key to what Doctor Who is. These can become a limiting factor for Doctor Who, as such assumptions become accepted universally not only as a feature of how audiences understand the show but are also expected as a matter of brand identity, acting as organizational functions that aid in the production and distribution of the series. These precedents form a set of qualities that define what Doctor Who must be, qualities that can become difficult for the series to meaningfully evolve beyond.

Tradition in the TARDIS

In the context of the companion, the precedents established by these serial expectations, therefore, function to keep these characters confined within a recurring, familiar, yet largely patriarchal narrative. Precedents leftover from the beginning of the series’ inception dictate that at any point in time, at least one sidekick will join the Doctor on their adventures. The original female companions were Susan (Carole Anne Ford) and Barbara (Jacqueline Hill), who carried with them arcs of ongoing mental maturity and rebelliousness toward the Doctor. Barbara especially begins the series as, representationally speaking, a fairly progressive character for the time – consistently pushing back against the abrasiveness of the First Doctor (William Hartnell). When conceiving of replacements for these characters, however, some of the least empowering elements of their personas were carried over to their immediate successors. Characters like Vicki (Maureen O’Brien), Dodo (Jackie Lane), and Jo Grant (Katy Manning) were all young, female, infantilized, and dependent on the Doctor – solidifying these qualities as assumed features for what the Doctor Who companion should be.

This does not mean that certain Doctor Who companions have not represented attempts to address these assumptions. Liz Shaw (Caroline John), Sarah Jane Smith (Elizabeth Sladen), Romana (Mary Tamm and Lalla Ward), or Ace (Sophie Aldred) were each in some way a modernization of the standard archetype, but each became undermined by the structure of the narrative they were attempting to redefine. These characters were often perceived as less successful as companions by production staff – most notably Liz Shaw and Romana I (Mary Tamm) – specifically because they violated the established gender dynamic of the show. This became dramatically emphasized in the departure circumstances of Liz Shaw.

Liz was conceived of as a scientific equal to the Doctor but only lasted on the show for a single season. Her replacement with Jo Grant – one presented without the fanfare of a proper departure scene – is often read as a specific result of her advanced scientific mind not fitting closely enough to the expectations that audiences and producers had for the Doctor’s female assistant.

Sarah Jane Smith has similarly been described as a character intended to respond to the feminist climate of the time and criticisms of how female characters were traditionally constructed on Doctor Who, and was optimistically described in some places as “the first of a new breed of companions for Doctor Who”. Sarah Jane was positioned as a ‘strong’ character who would identify herself explicitly as a feminist. Sarah Jane’s articulation of her feminism, however, operated within the flawed liberal framework of its apolitical presentation. As a result, Sarah Jane’s explicit feminism has been read as a reductive and limited understanding of second-wave feminism at best or at worst has read as a parody of feminism entirely while nevertheless failing to provide a significant change to the narrative structure of the companion at the root of the problem. Lorna Jowett has also noted that when Sarah Jane returned to the series in the revival episode ‘School Reunion’ (S2, Ep3) this feminist aspect of her character was all but abandoned, as she became largely defined by her past relationship to the Doctor.

“‘Did I do something wrong? Because you never came back for me. You just—dumped me.”

Leela (Louise Jameson) followed Sarah Jane as a companion designed to break these stereotypes further through a far more violent and assertive persona, yet Leela was also dressed in explicitly sexualized clothing meant to claim the attention of adult male viewers. The presentation of Leela’s character should be read through an intersectional lens as well, as Leela was also codified as indigenous. Originating from the Sevateem tribe on an unnamed planet, Leela is often presented as confused or mystified by technology and other “civilized” (read: “Western”) values. Leela is allowed the ability to challenge the submissive nature of the companion’s role only insofar as the threat of this challenge is mediated by the power of the camera’s ‘gaze’ and the patronizing colonial authority exerted over her by the text.

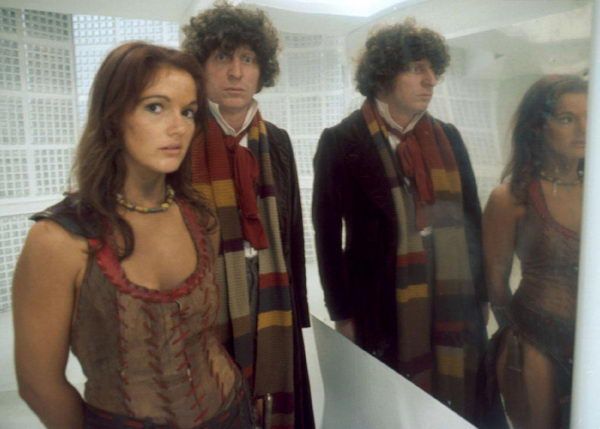

Perhaps the most notable attempt to reject the precedent of the companion as subservient to the Doctor was Romana (Mary Tamm, and then Lalla Ward), a character conceived of as a female Time Lord and therefore as the Doctor’s intellectual and scientific equal. While Romana would take on a position of authority with side characters more consistently than other companions, when placed next to the Doctor, Romana would continue to demonstrate a more traditional subservience. Romana was presented as holding a comparative naïveté to the Doctor, as her theoretical understanding of the universe was demonstrated as secondary to the Doctor’s practical, hands-on experience.

Mary Tamm’s “ice goddess” take on Romana was also met with a similar fate to Liz Shaw – to be unceremoniously replaced with a more subservient and conventionally feminine character after a single season. Although, instead of being deemed too intelligent to function narratively as a companion by the production staff, it was Mary Tamm’s dissatisfaction with the writing of her character as a “damsel in distress” that lead to her regeneration into Lalla Ward’s version of the character. As James Chapman summarizes in Inside the TARDIS: The Worlds of Doctor Who: A Cultural History (2006), “For all these valiant attempts to offer more positive female roles, however, most companions eventually slipped back into the traditional mold of ‘screamers’.”

This subservience may be strongly associated with the companion archetype, but it is also by no means the only version of the companion that Doctor Who has presented. Ace, for example, is positioned within the genre context of an explosive 1980s action sci-fi series but takes on the role of the machismo action hero in place of the Seventh Doctor (Sylvester McCoy). Ace’s placement as the last companion before the cancellation of the series in 1989 however, results in an inability for Ace to properly redefine precedents around the companion, with only the focus on her life outside the Doctor to be carried on into the revival in 2005 as a precedent.

Characters such as these appear throughout the classic run of the series but are more often read as deviations from the norm rather than offering a new definition of what constitutes normal. When each of these characters is followed by a replacement who would function more within the traditional role of the companion, this communicates that the Doctor/companion dynamic is allowed to be experimented with, but the format of the series requires that the companion must inevitably return to the patriarchal nature of its standard function. This is why it has been historically insufficient to merely produce a new companion character who functions better on a representational level. These characters are still written and read within the patriarchal archetype of the Doctor Who companion, a role largely recognized as ultimately subservient to the all-knowing figure of a male Doctor.

Just take this exchange from ‘The Ribos Operation’ (S16, Ep1).

The Doctor: I don’t suppose you can make tea?

Romana: Tea?

The Doctor: No, I don’t suppose you can. They don’t teach you anything useful at the Academy, do they?

The Gendered Vortex of the Companion Role

It is important to recognize this recurring problem as not merely the result of naïveté or malicious intent on the part of the production team, but more accurately a fundamental limitation that had by now been built into the very DNA of what Doctor Who was understood to be. Writers and producers of this series have historically demonstrated awareness of the patriarchal nature of the companion role, but have either been unsuccessful in correcting it themselves or demonstrated active complacency towards it. As Grahame Williams, the producer from 1977-1979, put it in Doctor Who: The Unfolding Text (1983):

“The function of the companion I’m sad to say, is and always has been, a stereotype… the companion is a story-telling device. That is not being cynical, it’s a fact.”

Williams is not the only Doctor Who producer to express concern over the problematic nature of the companion’s narrative role, with Barry Letts and John Nathan-Turner expressing similar critiques of the companion yet never being able to break the female characters they helped to develop out of this mold through their own work on the show. This is a problem that multiple producers and writers have aimed to resolve. To understand why they have failed, it is necessary to consider the role of the companion in the narrative structure of this series.

The central function served by the companion in the plot of a traditional Doctor Who episode is to ask questions about what is happening at any given moment in order to provide the Doctor with an excuse to deliver exposition about the narrative. The universe of this series is often complex and typically bizarre, toying with science fiction iconography in a way that can be pleasurable in its playfulness but requires both halves of a Doctor/companion dynamic in order to convey itself to a viewer. There needs to be a character with both access to information – where we are, what is at stake, etc. – and also the willingness to deliver that information.

There also needs to be a character who would reasonably ask the same questions as the audience to provide an excuse within the narrative for this information to be delivered. The reason why these companion characters are largely female and the Doctor character has largely been male is largely the result of a trope. It is a common convention within popular television narratives for female characters to ask questions that male characters have the answers to. The reasoning for this is purely ideological – a representational convention in which women are shown to lack knowledge that men possess, reinforcing unspoken codes of cultural patriarchy. The outcome here, intentional or otherwise is, as John Fiske puts it in Television Culture (2011), to “organize the other codes into producing a congruent and coherent set of meanings that constitute the common sense of a society.”

This question-answer function is necessary to the structure of Doctor Who but becomes limiting when it is drawn across a clear gender line and even further so when the companion forms the exclusive space that recurring female characters are expected to occupy. There have been many male companions, including characters like Ian (William Russell), Harry (Ian Marter), Adric (Matthew Waterhouse), or Rory (Arthur Darvill) – but the companion is not the exclusive space for recurring male characters. The Master (starting with Roger Delgrado), Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart (Nicholas Courtney), Sergeant Benton (John Levene), or Professor Edward Travers (Jack Watling) all made recurring appearances over more than one serial without taking on the role of a companion.