Contact (1997) is a modern-day story about a modern-day woman and is full of technology – after all, the world builds a spaceship when it receives a radio message from an alien civilization giving them the blueprints.

But its origins in fact stretch back to the 4th century C. E. “I had discovered Hypatia,” says writer Ann Druyan, co-creator of Contact, seminal science series Cosmos (1980), and Carl Sagan’s widow, talking about the oft-forgotten Hellenic philosopher and mathematician. “It was a time when it was very fashionable to say things like, ‘Well, if women are as smart as men, where are the female Leonardos and female Einsteins?’ [Hypatia] worked on equations that would later fascinate Isaac Newton and she was carved to bits with abalone shells and martyred for her troubles.

“And so that was kind of an answer, in our view, to what happens when women step out and become the heroes of their own story. Carl and I then determined that we were going to create a hero, a female hero who actually goes on a great odyssey and the men stay home.”

As told by

- Ann Druyan (co-creator and Carl Sagan's widow)

- Lynda Obst (executive producer)

- Dr. Bryan J. Butler (consultant; very large array)

- Geoffrey Blake (actor; Fisher)

Around the same time, in late 1979, producer Lynda Obst was at a crossroads. She had left The New York Times to try Hollywood and was working for a pugnacious executive called Peter Guber. She didn’t like her job all that much, but she did like hanging out with her friends Carl and Annie, who stayed in LA while finishing up the editing on Cosmos.

“I remember asking Carl if he had any movie ideas,” says Obst (now a veteran of films like Flashdance, The Fisher King, and Interstellar). “He said, ‘Actually yes, I’ve always had one about first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence. I thought, ‘That’s not a bad idea.’”

The Frustrating Road to Production

The core pitch was a simple one: scientists pick up an alien signal that apparently offers humankind a way to travel to their planet. A dedicated radio astronomer called Dr. Ellie Arroway who’s always dreamed about what’s out there in the stars gets picked for the mission. But being a Carl Sagan production, it’s not that straightforward. Instead, it does what great sci-fi does – asks big questions, interrogates the nature of faith, incorporates metaphysics, and even tackles the vagaries of scientific funding and geopolitical one-upmanship.

“We started to brainstorm it,” says Obst. “Carl brought in all of these fabulous experts. An expert on religion who he would debate all day long. And we brought in a futurist and we brought in some women to talk about what it was like to be a woman in science at that time and a radio astronomer. At the time, of course, there was no technology. So we literally had a court stenographer take down all of these tapes, [and] record all of our workshops. In fact, that’s how I met [Nobel Prize-winning physicist] Kip [Thorne]. Kip came to talk about wormholes.”

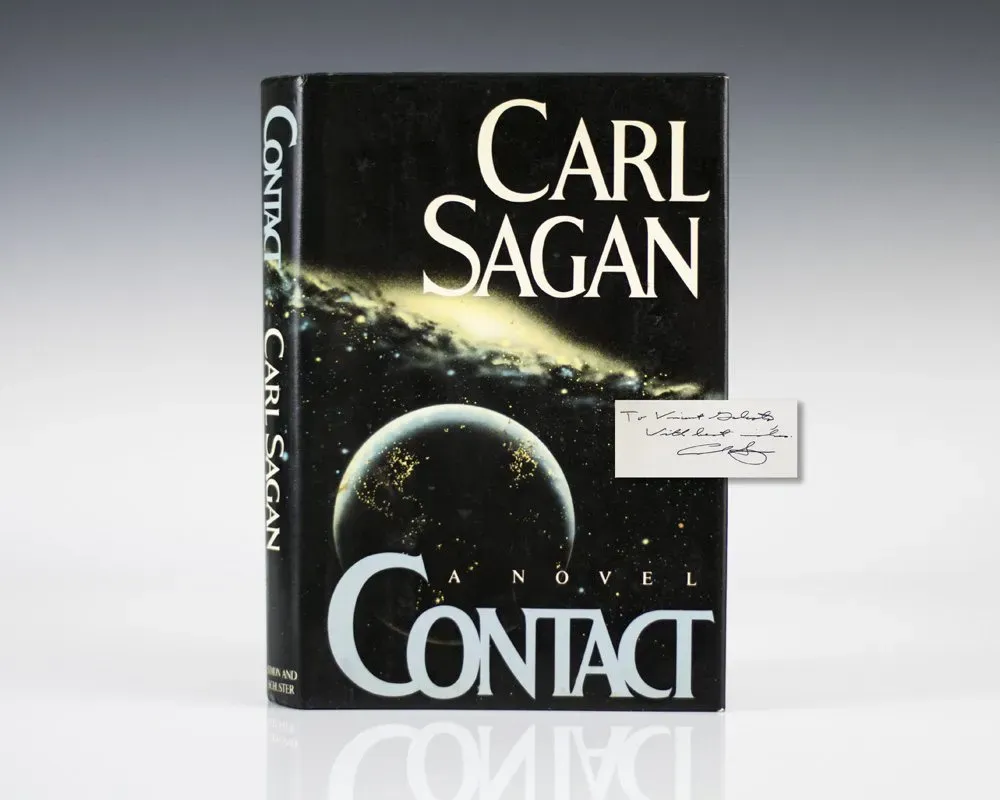

Sagan and Druyan took these discussions and used them to build a 110-page treatment. Interestingly, Druyan says it was done to be either a screenplay or a book, or both, at the same time. “The idea was that I would create all of the emotional and personal aspects of the novel, the very novel-y things,” she says. “And Carl, of course, would, of course, be the only one who could create a credible, plausible, science-based story of what that first contact would be.”

Peter Guber liked the treatment and started to develop it as a film. And pretty much in parallel, Simon & Schuster bought the novel. One of the timelines attributed to Contact is that the book only happened because the film wasn’t. Druyan disagrees. “It wasn’t like we can’t make a movie, let’s do a book,” she says.

But in truth, Contact the movie did start to fade from view. Development was tortuous under Guber. “He hired a series of terrible screenwriters,” says Obst. “Famous, but wrong.” She remembers one of them being the person who wrote the 1980 Dolly Parton hit ‘9 to 5’. Characters were added, from Ellie Arroway’s estranged son to a Native American astronaut. It looked like it would be one of those almost-but-not-quite stories. “In the late Eighties, it began to feel like a figment of our imagination,” admits Druyan.

But when the novel finally came out in 1985 and became a bestseller, Hollywood started to take notice again. Richard Donner’s (Superman) name was thrown around as a possible director, while Roland Joffé (The Mission) was also attached. However, Obst had now found her footing, and when she impressed Warner Bros. with the script for a movie about journalism called Above the Fold, one of the executives mentioned whether she might be interested in this Sagan sci-fi project they had.

“I almost burst into tears,” says Obst. “I said ‘They’re my best friends, I started that’. So they gave it back to me.”

Contact Finds its Director

And so that was it. Obst fired the scientific consultant, brought Sagan and Druyan back in and the script by James V. Hart was greenlit and made at the beginning of the 1990s.

…Only it wasn’t. Robert Zemeckis (Back To The Future) was suggested as a director but didn’t like the current screenplay, which, he told Entertainment Weekly, “was great until the last page-and-a-half. And then it had the sky open up and all these angelic aliens putting on a light show and I said, ‘That’s just not going to work’.”

And then George Miller (Mad Max) got involved. “I don’t think there could have been a better director for Contact than George,” says Obst.

“For me, the most thrilling part of the creative process… was when George Miller was going to direct it and the years that we spent working with George both in New York and Sydney.”

The problem was Miller was slow. He brought on another writer, Menno Meyjes (Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade), introduced the Pope as a supporting character, and approached Ralph Fiennes to play the key character of religious thinker Palmer Joss. “We’d finally gotten to a point where we had produced a script that [Miller] actually liked,” says Druyan. “We were thrilled. And it was the same day that Carl was diagnosed with the disease that ultimately led to three bone marrow transplants, two years of great suffering, and his death.”

But despite this, the director just wouldn’t commit to a start date. Warner Bros. called a big meeting and issued an ultimatum, but Miller refused, thinking they’d cave. They didn’t and Miller was fired.

“It was heartbreaking,” says Obst. “And the next day they gave it to Zemeckis.”

Because she was so closely connected to Miller, Obst wished them luck and remained on the project in credit alone. The script was reworked to have a more ambiguous ending and Matthew McConaughey was cast as Palmer Joss alongside Jodie Foster’s Ellie Arroway, while John Hurt, Tom Skerritt, and James Woods filled out the ensemble.

Sidney Poitier was approached to play the President but turned it down, so instead, the filmmakers hired Bill Clinton. Well, news clips of him – he had just given a speech about a Mars meteorite, and “it sounded like it was scripted for this movie,” said Zemeckis (the White House subsequently complained about Clinton’s appearance, arguing it was unauthorized and used to say things he didn’t actually say, but they didn’t seek an injunction). Sagan was brought in to give a scientific lecture to the actors. “It was one of those great Sagan seminars,” Foster told Starlog.

The Filming of Contact

Filming finally got underway in California and the jungles of Puerto Rico, as well as the most iconic of its locations – the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico, better known as that place in the movie with the massive radio telescopes that look like satellite dishes.

Dr. Bryan J. Butler worked (and still works) at the VLA and was signed up as a scientific consultant. “There was one antenna they wanted to do most of their filming on and they called it the hero antenna,” he says now. “We had to invent a mode of observing on the VLA antennas we called the Hollywood model. Normally when you observe a celestial source, you track it, so the antennas move with time. And they didn’t want that. They wanted to film and have the antenna be fixed.”

They also stopped the dish from getting its occasional paint job. Warner Bros. was worried that if the antenna looked too clean and fresh, audiences would think they’d CGI-ed it in.

Actor Geoffrey Blake (Forrest Gump) who played Fisher – one of the gang of key scientists alongside Foster, William Fichtner, and Max Martini – remembers Butler’s input, though not his real name.

“I always called him Dr. Birkenstock,” says Blake. “I’m big on nicknames, so I believe I gave him that.”

Having worked with her closely on-set – “she was fantastic, she knew the terminology” – when it came time for the cast and crew screening, Butler wanted to introduce his wife to Foster. “We approached her and she was in a group of people,” he remembers. “She turned to the others and said, ‘This is Dr. Birkenstock’. I had acquired this nickname because I always wore Birkenstocks on set, so that was fantastic.”

Filming itself went smoothly. “It was one of my favorite movies to make,” says Blake. Some of the science jargon was complicated, but they had Butler and others on set to help.

“Sometimes we would just confer with [Butler],” says Blake. “I would say, ‘Let’s start with good thing, bad thing – is what I’m saying a good thing, or a bad thing?’ He was a big help.”

Sadly, Sagan was very ill by this point. “He visited Bob [Zemeckis] on set during the filming in Washington, DC, and that was just about a month before Carl died,” says Druyan. “We had a wonderful evening with Jodie Foster. And she came to see us in Seattle, where Carl was getting his bone marrow transplants.”

Losing Carl Sagan

Little did they know, however, that there was a nasty surprise lurking around the corner, in the shape of legendary filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola.

“He saw Carl on television a few weeks before Carl’s death and realized that he was fatally ill,” says Druyan, still clearly upset. “And he prepared a lawsuit against me, his widow, which was to be held by his lawyer until Carl’s death. And I was served with a subpoena, as I tried to get back into my house, coming back from the funeral with my five-year-old son in my arms.”

Coppola was suing for a piece of Contact, arguing that he had made a contract with Sagan back in 1975 to develop a TV show about first contact with aliens.

“It was an astonishing big, fat lie,” says Obst.

Druyan says the pair did meet, but the idea there was a contract or even anything beyond a brief conversation, is nonsense. The Los Angeles Superior Court agreed – after countless depositions and court appearances, the lawsuit was thrown out.

“I never received an apology for him,” says Druyan.

Released on 11th July 1997 and costing $90m, Contact ended up taking $172m worldwide, not unsuccessful, but not a slam dunk. Still, 23 years later, it’s a film that endures more than many others in the genre.

“The elephant in the room was that it was Bob’s follow-up to Gump,” says Blake, suggesting it was never going to be as big a smash as the Tom Hanks Oscar-winner. “But it was one of the great experiences of my career and I think it’s a very underrated movie.”

Obst too likes the finished product. “In almost every way except for the very ending,” she says. “I think we saw different things in the ending.”

She still thinks Miller would have been a more suitable director. “George is a little more transcendent, you know?”

Nevertheless, she returned to the same themes for 2014’s Interstellar. “For me, they’re cousins, you know, because Kip [Thorne] and I are connected to both of them.”

The Legacy of Contact

For Bryan J. Butler, the movie was a fun pitstop on what’s been a successful scientific career. Towards the end of shooting, Zemeckis asked him to come up with some lines for a character and he got to shoot a speaking part, even though it was cut from the finished film.

“Because of that I get royalties from the movie,” he says. “For a while, there were actually sizeable. The cheque would be, I don’t know, 500, 600 bucks. Now when I get the cheques, they’re like eight dollars or something like that. I think that the lowest one I got was 29 cents. I kept that one.”

It may have taken 18 years to get to the screen, but Contact remains one of Ann Druyan’s most satisfying and intimate experiences.

“I remember sitting with Lynda at the premiere,” she says. “It was August, I guess, ‘97. And Carl died in December of ‘96. And I remember holding her hand and seeing the first three minutes and remembering Carl dictating those first three minutes into his dictation machine. He always carried two. And I remember him in our living room, dictating the pathway of the message.”

Indeed, the movie’s legacy stretches beyond science-fiction cinema and into actual science.

“In the years since, I have been so moved by how many people and particularly female scientists have told me that it was this movie that made them think that they could become a scientist in the face of all kinds of rejection because of their gender.”

“And this movie gave them the courage to persevere. One of the countless gifts of my life with Carl to me and our family is that I never worked on anything that wasn’t, in my view, really meaningful.”

This article was first published on February 2nd, 2021, on the original Companion website.