Star Trek: The Original Series ‘A Taste of Armageddon’ (S1, Ep23), February 23rd, 1967. Captain Kirk, First Officer Spock, and a small landing party depart USS Enterprise to land on the planet Eminiar VII. Upon arrival, they’re informed by the inhabitants that Eminiar VII is at war with neighboring planet Vendikar. To limit damage to infrastructure, both planets wage this war via computers, simulating the real thing.

Soon after their arrival, they’re informed that Enterprise and the city they’ve arrived at have just been destroyed in the digital war. But while the infrastructure remains, the treaty with Vendikar demands that all casualties in the war must be upheld. The city inhabitants, along with Kirk and his crew aboard Enterprise, must report being disintegrated, maintaining the treaty.

WarGames and the 80s Rising Hobbyist PC Culture

Artificial Intelligence and war have been married within sci-fi for decades. A logical conclusion to the horrors and difficulty of planning a war is that the war could be fought through an emotionless algorithm. No wrong choices will be made, no human emotions will get in the way of the correct course of action.

At the start of the 1983 movie WarGames, two United Air Force employees find it impossible to turn the key and launch missiles at the enemy despite having clear signs that the country is under attack. This attack ends up being a practice run that the employees were unaware of but their failure to react according to protocol convinces the American government to remove that human element and instead replace them with a computer named WOPR (War Operation Plan Response) that will act as needed.

At the time of the film’s release, The Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States was technically still ongoing; a tense period of worry built around mutually assured destruction that had begun to calm but remained relevant within the minds of audiences. It’s no surprise then that movies of the period discussed and reflected on the possibilities here.

David Lightman, played by Matthew Broderick, uses his computer skills to game systems. He hacks into airlines for free flights and adjusts his grades at school all from the comfort of his own bedroom. This method of hacking required having his computer dial out to random numbers across his desired location and waiting for a ping back from a computer. Once a ping back is brought, Lightman can manually confirm he has found the place he was seeking and get to work.

Seeking to play a new game coming out, Lightman starts calling out across California in hopes of hacking into the developer’s company and grabbing a copy of the game early. He soon gets a ping back from a line and checks it. Filled with the names of games like Falken’s Maze, Chess, and Poker, Lightman thinks he has found it. At the bottom of the list lies “Global Thermonuclear War.”

Soon after loading the game, he finds himself fighting a digital war against an AI, unaware that he is in fact playing out a simulation with WOPR itself and that his actions within this simulation could cause enough of a red flag for the machine to launch real missiles at their enemy. After attacking some US cities in the game (playing on the side of the Soviet Union), Lightman causes alarms to blare at NORAD (North American Aerospace Defence Command) as if they’re under attack. The unaware teen ends the game early and all returns to normal at NORAD, with none of them certain as to why they were just informed missiles had launched at major cities.

Lightman is soon picked up by the government and learns that while he had backed out of the game, WOPR hadn’t. To reverse the issues caused he will need to find the AI programmer and figure out a way to win the game of war against a computer that believes it is defending America.

The film plays out with the eventual final battle against the machine being Lightman and the original programmer challenging it to play Tic-Tac-Toe against itself. The computer, making all of the correct choices on either side, finds it impossible to win a match against itself. Realizing that war itself leads to no winners, WOPR cancels the game of Global Thermonuclear War as “the only winning move is not to play”.

WarGames is often cited as the reason that people get into tech. Many people within the industry have said that WarGames influenced their career choices following the movie's faithful exploration of hacking and the exploration of machine learning displayed in the final act. The film's impact led to policies being put in place regarding computer security and the opening sequence ended up becoming a reality soon after the film's release when Soviet Air Defence Force’s Stanislav Petrov refused to launch a missile in the middle of what was an early-warning alarm malfunction; the human element winning out and stopping a devastating end.

At the end of Kirk’s adventure against the citizens of Eminiar VII trying to push him and his crew into disintegration, Kirk destroys the computer simulating the war. With no way to simulate the war, the citizens begin to panic about the reality of having to fight the war for real. Kirk encourages them to speak to their rival planet instead. With no computer between the conflict, the dawning reality of what fighting the war would do might be enough to bring it to an end. Vendikar and Eminiar VII call a ceasefire and begin to negotiate peace as the episode comes to a close.

Speaking in an interview with Wired about WarGames, Kevin Mitnick, a hacker who served five years in prison for computer crimes pointed to WarGames and society’s misunderstanding of computers as a reason for his harsher treatment.

“That movie had a significant effect on my treatment by the federal government. I was held in solitary confinement for nearly a year because a prosecutor told a judge that if I got near a phone, I could dial up Norad and launch a nuclear missile. I never hacked into Norad. And when the prosecutor said that, I laughed — in open court. I thought, “This guy just burned all his credibility.” But the court believed it. I think the movie convinced people that this stuff was real. They tried to make me into a fictional character.”

Mitnick’s quote brings to light a larger issue regarding computer programming and hacking at the time. While WarGames was fictional and the cold war came to an end, not many people really understood what the reality was when it came to computers. The fears of the digital age progressed and as we neared the millennium the concept of a “Y2K bug” caused panic.

Digimon, the Millennium and Computer Literacy

The Y2K panic focused on the fact that when systems were built for computers, they weren’t programmed to go beyond the year 1999. The date settings on a calendar using the final two digits of a year may not understand the shift from 99 to 00 and this may cause things to fail. With a large amount of infrastructure going digital, the fear was that Y2K would bring about the apocalypse as the clocks would revert to zero and cause worldwide system failure.

The reality ended up being a lot less of a panic than people thought. Programmers worked hard in the 90s to fix their systems in prep for the millennium rollover and there were almost no negative effects. But as with the Cold War and WarGames, the Y2K panic caused an interest in creatives to explore the possibilities. On March 4th, 2000, Mamoru Hosoda released the movie Digimon Adventure: Our War Game! The film, a tie-in to the popular children’s animation series Digimon, reimagined the WarGames scenario for a more modern audience of the time.

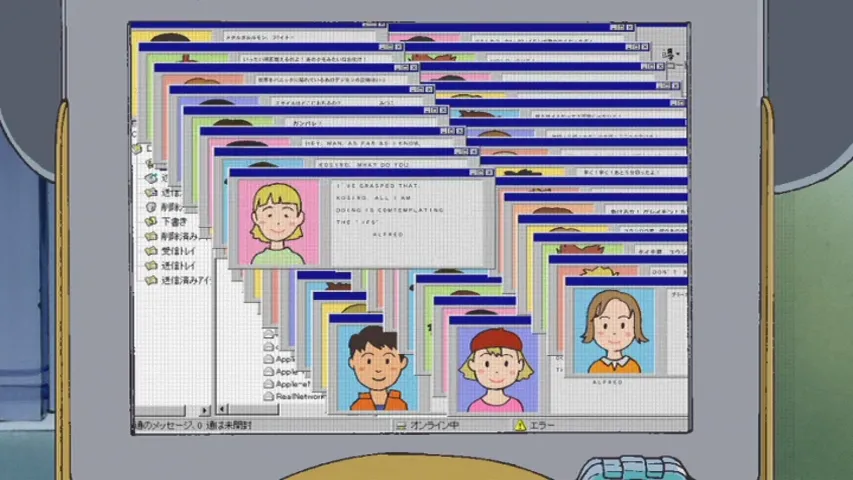

No longer about nuclear stand-off, Our War Game focused on the possibility of a literal Y2K bug destroying digital infrastructure while our lead characters attempt to stop it. The threat evolved from a scenario run that could end in war to an active combatant with a ticking clock before everything came to an end. Hosoda’s movie featured lead characters Taichi and Koshiro locked to their computers as they tried to stop the bug from destroying everything live.

A loving time capsule to late 90s technology, Digimon: The Movie (2000) (which cobbled together Our War Game and the first Digimon Adventure into a single film for the US) smartly utilized flaws in tech at the time to pair down the core cast of eight children from the show to focus primarily on four of the main characters. The bug takes down phone lines and messes with train times to help keep some of the cast away and unreachable. Only those actively aware of the issue (and with an internet connection) turn up for this brisk 40-minute action movie.

The final battle has the kids and their digital companions fighting against the clock as a missile is about to hit their city and detonate if they don’t destroy the bug before a countdown ends. With the world being able to witness the war live online, Koshiro advises anyone watching to email him so that he can direct it to the bug itself and cause it to slow down, leaving it open to attack.

Our War Game isn’t exploring tech as deeply as WarGames did, the evolution of our digital age allowed the WarGames scenario to be reimagined for an audience that had a grasp on what they were looking at when it came to computers. While WarGames HAD to explain itself, Our War Game was released at a time when the home computer was a much more common thing. People may not have understood what RAM did but they knew a computer would slow down under a heavy load of new information being delivered at once.

Digimon: The Movie showed that while the WarGame scenario wouldn’t become a genre, it did have the capacity to evolve and reflect certain eras of technology and computer literacy. But while Digimon arguably celebrated computer literacy, the start of the millennium brought about new worries as a dependency on digital tech for personal satisfaction lead to a level of social disconnect with users.

In 2001, director Kiyoshi Kurosawa explored the effects of technology on the psyche with his feature horror film Kairo, also known as Pulse. While Kairo’s concept of ghosts bleeding into our world through computers doesn’t seem to reflect much of an era, the movie itself puts a heavy focus on the disconnect between people as computer screens begin to take up more of our focus.

This heavily depressed horror movie forgoes trying to scare us with jumps and freaky imagery and instead sits in a quiet place of contemplation as characters are overwhelmed by sadness to the point of ceasing to exist. The ghosts in this movie are alone, sad, and unaware of who or what they even are. Kairo is a movie aware of the fact that the concept is scary enough and that grounding its characters in the sad reality of what’s happening is enough to scare us all the same.

While media focusing on the internet like Hackers (1995) and The Matrix (1999) were taking off in the hearts of tech enthusiasts and children’s media like Our War Game could start discussing technology as a known thing; Kairo was a look at the worries of an unmeasured response to all that digital tech can give us.

Speaking to IGN in an interview for his movie Cure (1997), Kairo director Kurosawa was asked what terrified him.

“Terror, I think, has many different levels. Changing into something different isn’t that scary. Well, maybe a little bit. But I think what’s scarier than that is not changing at all. Becoming the same forever, without any transformation whatsoever, I think that is truly terrifying. And if you add to that, the condition in which you are the same forever without any alteration, I think the condition that most clearly embodies that is death itself.”

There was and does remain a fear of technology making us complacent. Instead of taking an active part in the lives of others, it becomes easier and easier to scroll a feed to keep updated with strangers. A computer does have the ability to maintain connection and interact with strangers but Kairo is careful to frame the reality of the action as that of sitting in a dark room alone, hoping those connections are enough to keep on living.

Summer Wars and Social Media in the 2010s

While the early 2000s internet age seemed unclear, interconnectivity began to come together towards the end of the decade as social media began to boom. AOL chat rooms with strangers shifted to websites like Myspace and Facebook that allowed you to keep the closer, real-life connections we shared an active part of our existence.

In 2009, Mamoru Hosoda would revisit the WarGames plotline for an updated revival, this time away from the constraints of a children’s entertainment franchise. The movie Summer Wars featured a virus taking over the profiles of the elite in a digital space to cause mass disruption across the world.

This time, a young boy named Kenji is whisked away with the girl he likes to attend her grandmother’s 90th birthday party. While there among a family of strangers, he accidentally hands a virus the keys to the world’s largest social media platform and all hell begins to break loose.

A feature-length move away from the Digimon Movie has Summer Wars no longer trying to narrow down the cast to a small few in a battle, but instead celebrating a large family unit that can come together in a time of need. As systems crash and traffic comes to a standstill, the focus is no longer on potential missile launches that could wipe us out (although it certainly does feature one) but instead turns a larger eye towards those that would need immediate help if everything shut down.

The drama becomes more real here as the elderly perish in situations that didn’t need to be fatal to them if the health service could operate as intended.

Action still plays a part early on as the largest gamer in the family, Kazuma, attempts to fight the virus in the digital world but the third act smartly removes the action from spectacle to focus on what social media can give others; the connections they need, literally. Each member of the family has a different job in wildly different industries and though they don’t always get along with each other they are able to use their own individual connections to come together as a family and make the fight online possible with a luck of the draw.

In WarGames, they defeated WOPR by making it fight against itself but in Summer Wars, the option to make a virus programmed for destruction fight itself just isn’t possible. Loading up Japanese card game Koi Koi against the virus allows the family to bet their own accounts against the virus’ stolen ones in an attempt to bring back the services they need.

Users across the world still in control of their accounts begin to offer their own digital avatars to the betting pool, giving our leads the chance to defeat the virus. This blend of digital world and familial closeness celebrates the early 2010s when social media grew to blend our digital lives with our personal. No longer were strangers the focus of a digital space, it was family.

Hosoda’s cinema, starting with Summer Wars, began to celebrate family and the connections he had made in life. Summer Wars focused on the importance of maintaining a familial connection and highlighted the importance of social media’s role in that.

“I got married. And it was great, but you know, being an animator I’m pretty used to my solitude. Getting married means in-laws. Suddenly I had all of these new family members, and I was really struck by how those interpersonal relationships work. It takes a lot of effort, and sometimes those new family members are hard to deal with, but you can also make a very deep connection with a total stranger. That really meant a lot to me. I never really thought about the idea of “family” being the theme of a film before, but somehow it just clicked into place.”

As Hosoda celebrated the family connection of social media, the decade of internet-based cinema following focused on the negative impact of social media. As teens develop connections with their friends in school, the school experience evolved from something that happened exclusively within the grounds of a playground and suddenly stretched beyond.

The Emily Osment-led Cyberbully (2011) focused on the inability to get away from those that want to mistreat you with social media taking up a large part of our lives. 2010’s Trust and Catfish detailed how easy it is to hide your true identity online and use a made-up persona to manipulate or prey upon others.

With the internet now a core part of the human experience, cinema surrounding it adjusted to become a cautionary tale. There are very real threats to introducing others to the internet without the means to navigate it safely.

Belle, Coronavirus, and the True Self in Digital Spaces

As things moved towards 2018, director Aneesh Chaganty’s feature film Searching managed to highlight an interesting aspect of digital living, detection. The story, which took place entirely through computer screens, managed to tell a heartfelt and engrossing story about a man’s search for his missing daughter via her online activity.

A year prior in 2017, actor Shia Labeouf had started the project He Will Not Divide Us, a live-streaming piece of art meant to protest Donald Trump’s presidency. Very quickly the users of the website 4chan decided to troll the piece by turning up to the live-streamed camera and saying offensive things. This caused Shia to move the project to a live stream of a flag in an unknown location. Not to be beaten, 4chan got to work and located the flag by following the flight paths of planes in the background of the stream to figure out the exact location, quickly managing to disrupt it once more. The internet’s war against a flag and Searching’s digital detection plot managed to highlight how a strong digital presence can be used for more than just nefarious means.

Cut to 2021, a world still in the grips of the coronavirus pandemic, only just coming out of lockdown. A large portion of the population had shifted to digital workspaces and classrooms to avoid physical interactions and keep the spread of the coronavirus down. This small pocket of history is still quite fresh having only just gotten to 2023 so media is still to come that will cover the period but a large part of the early lockdown focused on how people maintain their connections.

The conferencing platform Zoom exploded in popularity as friend groups hosted movie nights and quizzes in an attempt to remain connected to each other. The internet had finally become the most important thing to us as it became the platform for connection, work, school, and most other forms of entertainment.

Media depicting the lockdown focused on the struggle to not enter that lonely depressed space that films like Kairo had warned us of long before. The lockdown special episode of Apple+ show Mythic Quest had lead character Poppy breaking down as isolation became too much for her.

The need for digital connection was huge but more importantly, the ability to be away from home had been lost to those that might need it most. At the start of 2021, the BBC reported that the number of reported incidents surrounding child abuse had risen by 27 percent during lockdown.

Iryna Pona, policy manager at the Children’s Society said:

“During the first lockdown many vulnerable children were stuck at home in difficult, sometimes dangerous situations, often isolated from friends and support networks.”

As the realities of lockdown came to an end and people returned to traditional living, Hosoda released his 2021 feature animated movie Belle, once against adapting the digital space concept he had worked with in Digimon: Our War Game and Summer Wars, though this time he adjusted from saving everyone to saving just one.

Exploring the concept of digital identity vs true identity, Belle features the character of Suzu, a shy teenage girl who becomes a famous singer in the virtual space under the persona of Belle. Through here she encounters a beast, this film’s version of the virus from Summer Wars, that is being sought out by admins or removed from their digital world. The beast angrily explores cyberspace, destroying anything he can to cause the most chaos. A chance encounter with the beast leads Suzu to want to learn more about him as we discover he isn’t a virus but another user.

Her investigation eventually leads to her discovering that the beast isn’t causing chaos for fun, but as a way to lash out online. The beast is a young boy, suffering from abuse at the hands of his father. In the final act, Suzu accidentally unveils him to the world and attempts to convince the boy to tell her his location so that she can send help. “I’ll help you, I’ll help you, I’ll help you,” he repeats angrily. He’s heard it all before and he can’t trust Suzu to help him while she’s hiding behind a digital identity.

As the boy cuts off the call, Suzu jumps back online and strips the image of the famous singer Belle that she had developed, revealing herself as the shy teen she is. hoping that the boy sees this action and knows he can trust her, she bursts into song as the world watches and slowly the world begins to sing back. While WarGames, Digimon, and Summer Wars focus on the few coming together to save the world, Belle opts to focus on the world coming together to save just a single person.

Speaking to Gizmodo in an interview about Belle, Hosoda said:

“If you rewind the clock back to Summer Wars, I felt that there was a clear line, or distinction, that where we exist right now is reality and what the internet is, is a tool of convenience in many ways. And that line was very clear. Fast-forward to today and Belle, and I think there’s definitely this idea of two realities.

So the current reality we occupy and exist physically, we have one face or facet of ourselves, but on the internet, we project a much different image. I think we can relate to this. But I’d argue all of these are what completes that person, and both of those are real in many ways. So, Suzu and Belle may feel like polar opposites of the spectrum— and they’re very different—but the same. I think this is something we can all relate to if we look at how people perceive us and what we try to project.”

Suzu shows herself online and is able to sing openly, no longer hiding behind the image of Belle, accepting that she can be herself physically and still perform. The beast comes back online having seen her performance and goes to reveal his location before being cut off by his father.

Our lead characters, similar to how Searching and 4chan had revealed themselves able to do so, come together to investigate what they know of the boy in hopes of finding him. The sound of an announcement in the background gives a vague area to look at and mapping the perspective of the building outside his window in that area allows them to find a street the kids likely live on.

Suzu breaks the walls of the digital space to seek them out in reality, confronting the boy’s father and standing as a protector. The internet in today’s day and age, following lockdown, provides a secondary outlet for those in need; A place to connect with others and find ways to help them.

Hosoda’s trilogy of digital content gives us a single vision through which to experience the digital space and public perception of it over time. Digimon explored the Y2K panic and the WarGames scenario through a computer-literate perspective. Summer Wars would go on to explore the advent of social media and familial connection under the same conceptual banner. Belle tackled the wider ability of the internet to be used to help those that need it, serving as an outlet for our true emotions and selves. The internet now stands as our own private corner to exist when the real, outward world keeps us from individual expression.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂