In a Spin magazine interview marking the 20th anniversary of his band’s 1995 album Clouds Taste Metallic, The Flaming Lips frontman Wayne Coyne was asked about their involvement with the soundtrack for Batman Forever, an album described by interviewer Dan Weiss as, “Even by ‘90s standards… one of the weirdest batches of artists.”

Coyne – reportedly not a fan of the finished film itself, though he enjoyed his group’s aural appearance – had this to say:

“I think it set up a blueprint that you could really have an interesting soundtrack that really doesn’t have that much to do with the movie and people would accept it. It was just a record that had another branding that went with it. I thought that was really a cool move, that it didn’t always just have to be a group of popular artists doing something to promote the movie. It really was a weird mixtape collection that had a movie with it too.”

A packed film soundtrack of popular music wasn’t a concept born in the 1990s, nor is it something that’s completely died out since, but various factors have led to that decade being the peak ‘music from the motion picture’ era, and how Coyne describes the Batman Forever soundtrack is reflective of why. And in the year 2020, Batman Forever’s album stands out as one of its decade’s most emblematic musical artifacts for how it both followed trends and also bucked the system in a way that arguably influenced the construction of soundtracks going forward; Entertainment Weekly ran a non-review article the summer of release on the extent to which the soundtrack was an outlier among its field.

To accompany a blockbuster designed to appeal to as many audiences as possible, with a massive promotional budget to ensure it did, the soundtrack covers almost every popular music base at that time – or what soon would be very popular. Referring to the end result as “patchwork”, Entertainment Weekly’s B- review of the album in 1995 said:

“Batman Forever is a grab bag of pop and rock tunes without any sort of unifying theme. Much like the movie and its engulf-and-devour marketing strategy, the pop soundtrack (not to be confused with the instrumental-score disc) aims for the most diverse cross-section of record buyers possible.”

Here’s the running order of artists on the 14-track album: U2, PJ Harvey, Brandy, Seal, Massive Attack (with Tracey Thorn of Everything but the Girl), Eddi Reader, Mazzy Star, The Offspring, Nick Cave, Method Man, Michael Hutchence, The Devlins, Sunny Day Real Estate, and The Flaming Lips. Almost every notable music genre in vogue during the mid-90s is present, via already big artists or rising stars, on one compact disc, which jumps from rap to power ballad to pop-punk to R&B to trip-hop to early emo to folk-pop to whatever genre within which you might plausibly place The Flaming Lips. If the global dominance of Los del Río’s ‘Macarena’ had happened just one year earlier, something like that song could conceivably have shown up on the Batman Forever soundtrack.

To properly understand the album’s legacy, one must first assess the context surrounding both it and the film’s making. And it’s probably best to start with the movie because the Batman franchise was in an interesting position when Batman Forever went into production.

A Batman for all Seasons

While 1992’s Batman Returns was commercially and (generally) critically successful, Warner Bros. higher-ups were reportedly disappointed with the box office results. The film made US$150 million less than its predecessor, with studio executives attributing the perceived underperformance to the sequel’s considerably darker and kinkier aesthetic and tone. This idea was partly supported by McDonald’s shutting down their Happy Meal tie-in for the movie in response to a parental outcry concerning the film’s violence and sexual references being inappropriate for children going to see the PG-13 feature. As 1989’s Batman had been an industry game-changer in terms of the extent and scope of its marketing and merchandising opportunities (including a multi-platinum soundtrack album by Warner-signed Prince), course correction to a more broadly family-friendly approach for the third film was appealing.

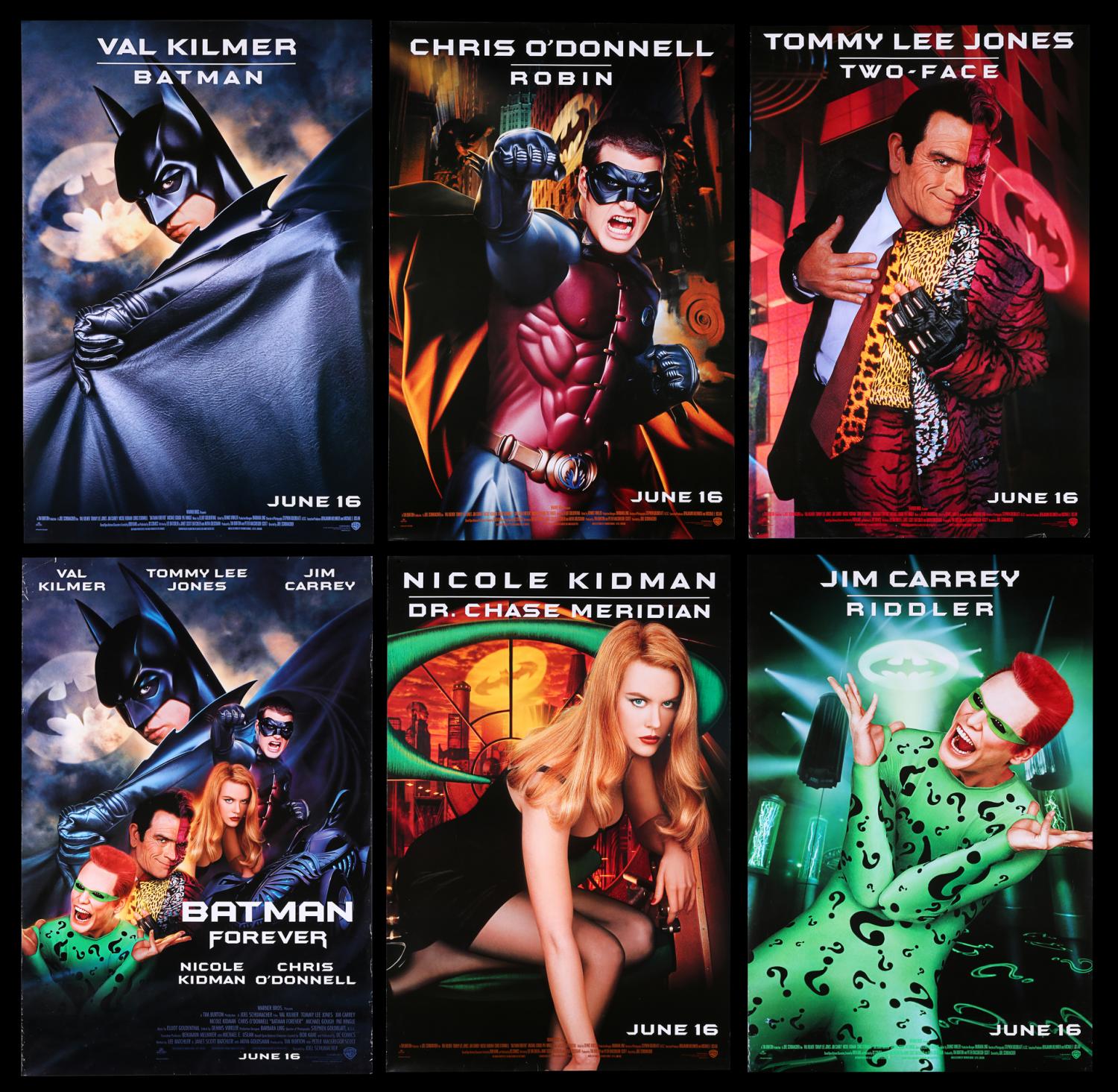

Tim Burton stepped down as director of the franchise, staying on in a producer capacity for Batman Forever and selecting replacement director Joel Schumacher. Although reportedly happy with the choice of Schumacher, Michael Keaton later turned down US$15 million to reprise the title role on the basis of wanting to pursue new opportunities and not liking the way the series was heading as pre-production developed. Val Kilmer was cast as a younger Bruce Wayne, with the rest of the main ensemble filled with actors whose stocks were very much on the rise at that point: Tommy Lee Jones, fresh off an Oscar win for The Fugitive (1993), as Two-Face; Chris O’Donnell as Robin, after the character (cast with Marlon Wayans) had been cut from Batman Returns’ shooting script before filming; Nicole Kidman as love interest Dr. Chase Meridian; and Jim Carrey – an extremely hot commodity after three back-to-back smash hits (Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask and Dumb and Dumber) in 1994 – as The Riddler. Michael Gough and Pat Hingle returned as Alfred Pennyworth and Commissioner Gordon, respectively, for some semblance of continuity with Burton’s films, even if the onscreen world of Gotham was to look very different indeed. And sound different, too, as Elliot Goldenthal replaced Danny Elfman to compose a considerably more operatic score for this interpretation of the Dark Knight.

Further Reading: The Mars Attacks Score

One of Danny Elfman’s ost unusual scores - Mars Attacks! | Danny Elfman on the Tim Burton Break Up and Make Up

The highest-grossing film in North America in 1995, and the sixth-highest worldwide, the movie’s general reputation nowadays is mostly along the lines of, “at least it’s better than Batman & Robin.” Schumacher’s two Batman films understandably get conflated together in people’s minds because they are direct sequels and many (though not all) of the perceived failings of Batman & Robin (1997) stem from creative decisions made during the production of Batman Forever; most notably the camper tone in comparison to Burton’s Batman Returns, the general direction of both the Batman comics of that era and the popular animated series still airing. Batman & Robin just doubles down on Batman Forever’s own maximalism.

But for all of the shared features between Schumacher’s Batman pair, Batman Forever is doing something different to its far more child-friendly follow-up. Your mileage may vary as to how successful any of it is, but there is a recurring attempt to explore the psychological theme of duality as it pertains to Bruce Wayne, and how he is coming to terms with repressed trauma concerning perceived guilt about his parents’ murder. Despite the supposed family-targeting goal, it’s at least flirting with darker, arguably more adult material, even if that rarely intersects with the other plot threads in any meaningful and ultimately satisfying fashion. And speaking of adult material, Kidman’s Dr. Chase Meridian, a psychologist fascinated by Batman’s dual nature but also extremely eager to hook up with the caped crusader, may well be the horniest main character in any PG to PG-13 rated blockbuster.

As realized by Schumacher, Kidman, and the shooting script, the romantic subplot of Batman Forever brings to mind Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (1987), which was originally envisioned to be more of a family-aimed vampire adventure, modeled on original director Richard Donner’s own The Goonies (1985). When Schumacher was approached to take over directing duties on The Lost Boys, he reportedly insisted on raising the ages of the younger characters, getting screenwriter Jeffrey Boam to revise the script and make the film more adult when it came to gory violence and sexual awakening. Likely still Schumacher’s most fondly remembered film, The Lost Boys doesn’t quite escape the vibe that it’s a kids’ film that had teen horror movie trappings bolted onto it.

Seemingly incompatible elements stitched together is kind of the ethos of Batman Forever as a whole. It’s there in the plotting but even more present in the aesthetic, specifically Barbara Ling’s production design. The film’s large sets combine hallucinatory interiors (slathered in what looks like glow-in-the-dark paint) and Tokyo-inspired neon exteriors with towering statues, where the shapes of human bodies and faces appear to be holding skyscrapers or circus venues in place. One might argue that modern Tokyo architecture and gothic don’t exactly go together very well, but the result is a big world of kitchen-sink visual sensibilities that you’ve never really seen before, even three films into a mega-franchise; although Schumacher, in an audio commentary for the film, suggested that the Japanese city influence was down to him wanting to “give you the colors of a comic book,” pointing to the kinds of Batman stories in print that he read growing up.

The design mix doesn’t make a huge amount of sense, but it’s certainly memorable. And for a mid-1990s blockbuster built on specific ideas of what a superhero adaptation was, memorable and glorious excess was more important than the relative plausibility you would find in Christopher Nolan’s later more grounded take on Gotham. As would be the case to an even more extreme degree in Batman & Robin, some of the design work was made with merchandising potential in mind – from McDonald’s toys to inspirations for video game levels. And then there’s how the film’s world as designed and plotted could inspire the artists contributing songs for the soundtrack.

The Sound of Violence

Batman Forever: Music from the Motion Picture went double platinum in the United States, though, somewhat amusingly given the album’s title, only five of the songs actually make an appearance in the film itself. In a July 1995 article for Entertainment Weekly by Chris Willman, Val Azzoli, the president of Atlantic Records (which released the soundtrack and whose parent company is Warner Music Group), is quoted as saying, “I think we’re gonna have to start doing ‘Inspired by the Motion Picture’ titles,” which Willman posits as “floating an accuracy-in-billing idea that came too late for Batman.” The album has since been titled Batman Forever: Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture on some reissue copies, including its relatively recent debut on vinyl.

In Batman Forever, U2’s ‘Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me’ and Seal’s ‘Kiss from a Rose’ play over the end credits; Brandy’s ‘Where Are You Now?’ and The Offspring’s ‘Smash It Up’ (a cover of a song by The Damned) briefly feature back-to-back during Robin’s night-time joyride in the Batmobile; and The Flaming Lips’ ‘Bad Days’ is more prominently used as the viewer gets their first look at the apartment of Edward Nygma/Riddler. That said, the lyrics for the last of those are genuinely relevant to the scene in question. At this point, Nygma is not far removed from the murder of his Wayne Enterprises work supervisor, Fred Stickley (played by a strangely uncredited Ed Begley Jr.), which he has made to look like a suicide, and is currently plotting revenge on his employer Bruce Wayne for not seeing the merit in his device that can beam television signals into people’s minds. Wayne rejects the device on the basis that the technology could be used to manipulate minds, which it of course later does when Nygma mass-produces it. The verses of ‘Bad Days’ perfectly complement the character’s psychology at that moment:

You’re sorta stuck where you are

But in your dreams you can buy expensive cars

Or live on Mars

And have it your way

And you hate your boss at your job

Well, in your dreams you can blow his head off

In your dreams

Show no mercy

Signed to Warner Bros., The Flaming Lips were approached to contribute a song to the Warner film’s soundtrack during the creation of Clouds Taste Metallic. ‘Bad Days’ was apparently the only new track they had ready to go at that point. According to frontman Wayne Coyne in that aforementioned Spin magazine interview, “They actually loved it and built the scene in the movie around the song. We were on this crazy giant record with U2 and Seal, who was a big pop artist at [the] time. Then we were thinking we didn’t want ‘Bad Days’ on Clouds Taste Metallic and on the record itself there’s a big gap, then it comes up at the end.”

That pre-recorded song accidentally had relevance to the film. Other artists on the soundtrack seem vaguely inspired by the film’s story or the world of Gotham, without being too overt – Nick Cave’s ‘There Is a Light’, to name one, seems to allude to the Bat-Signal with its chorus, though it’s generalized enough to plausibly slot into Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ most recent album at that time, Let Love In (1994). Only one contributor went full-on explicit with referencing Batman and the film itself. Method Man’s single ‘The Riddler’ is a first-person interpretation of the villain with one jarring motif: Method Man calls himself Johnny Blaze sometimes, but putting that name in lines of his song ‘The Riddler’ for the Batman Forever soundtrack has the same energy of Rollins Band covering Suicide’s ‘Ghost Rider’ for The Crow (1994).

Seal’s multiple Grammy-winning ‘Kiss from a Rose’ was previously released as a single in 1994 and even featured in that year’s The NeverEnding Story III. Though a modest success in certain countries in 1994, the song’s fortune skyrocketed as the second single from the soundtrack, topping the Billboard Hot 100 with the accompaniment of a Schumacher-directed music video. U2’s ‘Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me’, meanwhile, had origins in sessions for the band’s 1993 album Zooropa, though their involvement with the soundtrack began when Schumacher conceived of a cameo role for Bono, as his concert alter-ego MacPhisto, within the film itself. They eventually decided it wasn’t suitable for the movie, though the animated music video for the song involves MacPhisto and the band in Gotham City.

U2 reportedly received a US$500,000 advance for their song. Chris Willman’s Entertainment Weekly report from the time also suggests The Offspring got US$250,000 for their The Damned cover, one of three cover versions on the album, the others being Michael Hutchence’s darkly menacing interpretation of Iggy Pop’s ‘The Passenger’ and Massive Attack and Tracey Thorn’s take on The Marvelettes’ ‘The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game’. If those big paydays are reflective of what the rest of Batman Forever’s contributing artists received, it’s no surprise that the next few years’ worths of aspiring blockbusters were often stuffed with both big and sometimes unexpected musicians in their wider marketing. Who could have foreseen that Space Jam (1996), a film about Michael Jordan playing basketball with the Looney Tunes would unite the musical forces of Method Man, Busta Rhymes, LL Cool J, Coolio, and B-Real of Cypress Hill for a song?

Further Reading: Score of the Worlds

Everything Everywhere All at Once | Rafiq Bhatia on Son Lux's Epic (and Eclectic) Score - It sounds like a Zen koan: what does Everything Everywhere All at Once sound like? Son Lux's composer Rafiq Bhatia explores the glorious anarchy.

Many of the biggest-selling soundtrack albums of all time – Saturday Night Fever, Purple Rain, and Grease to name just three – are connected to films that are either outright musicals or where a relationship with music is a key part of the film’s narrative. Soundtracks for musicals or music-adjacent films certainly didn’t lose their appeal in the ‘90s, as evidenced by the success of The Lion King (1994) and the album for The Bodyguard (1992) being the biggest-selling soundtrack of all time. But outside of those genres, the decade saw a massive upswing in both commercial success and cultural footprint for soundtracks largely made up of recordings originally commissioned for that movie and album. The Space Jam (1996) album, which centered on hip-hop, rap, dance music, and soul (and also featured a Seal contribution), went six times platinum in the United States. A year before Batman Forever, the goth and alternative rock-focused album for The Crow topped the Billboard chart and sold 3.8 million copies in that country alone.

These were albums that transcended being mere movie memorabilia. In some cases, they distilled specific cultural moments beyond just the film they were linked to – the soundtrack for Cameron Crowe’s Singles (1992) is widely considered to have helped crystallize Seattle’s ascendant grunge scene in the mainstream consciousness. A certain zeitgeist was also captured by many bestselling soundtracks that were either assembled entirely from back catalog cuts (Pulp Fiction) or that combined a roughly even mix of the old and new (Trainspotting).

While soundtracks of this nature are still around nowadays, it is rare that as much expense and effort is poured into the creation of one as a standalone product. Much of that can likely be attributed to shifts in the music industry at large around the start of the 2000s. Record labels were making and spending a lot more money in the 1990s before the rise of digital music and the threats it presented, so it stands to reason that tightening compilation budgets was a high priority. Outside of the ever-enduring musical genre (The Greatest Showman, Frozen), some of the more noteworthy soundtracks of the modern era have tended to be comprised of exclusively older songs (Guardians of the Galaxy), or cases where platinum-selling artists are eschewed entirely in favor of a collection of smaller though buzzy names providing original songs for guaranteed money-makers, in the hopes of getting younger viewers into the music – see the indie rock-focused soundtracks for the Twilight sequels.

For certain big movies, a trend of late is the hiring of specific popular artists to curate and control their own vision for a soundtrack with a certain theme in mind, such as in the case of Kendrick Lamar’s work on Black Panther (2018) and Beyoncé’s two concept albums in support of the 2019 remake of The Lion King. As with ‘90s powerhouse soundtracks for the likes of The Crow and Space Jam, or even Prince’s 1989 album for Tim Burton’s Batman, these collections tend to focus on two to three relatively similar genres at most for the sake of a consistent atmosphere.

25 years on, the soundtrack for Batman Forever, much like the film it represents, persists as a favorite for many because it so gleefully ignores traditional stylistic consistency as a prerequisite. The rhyme and reason for its sequencing and selection remain a puzzle worthy of The Riddler.

This article was first published on November 18th, 2022, on the original Companion website.

Further Reading on All Topics

- One of Danny Elfman’s ost unusual scores - Mars Attacks! | Danny Elfman on the Tim Burton Break Up and Make Up

- Everything Everywhere All at Once | Rafiq Bhatia on Son Lux's Epic (and Eclectic) Score - It sounds like a Zen koan: what does Everything Everywhere All at Once sound like? Son Lux's composer Rafiq Bhatia explores the glorious anarchy.

- Lexx | ‘Brigadoom’ – How We Made the Infamous Musical Episode - Beating Buffy the Vampire Slayer to the punch, this is the story behind the musical Lexx episode ‘Brigadoom’ as told by the cast and composer.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂