Pat McClung is a man who found himself in the right place at the right time. After a stint in the US Army as a young adult – where he worked on telephone switching equipment – he became a model shop expert specializing in miniature work on some of the biggest sci-fi motion features of all time. But it was when McClung was catapulted into visual effects at the start of the 1990s he realized he was part of a digital revolution that would change the movie business.

Not many can say the first feature they worked on was a major science fiction blockbuster extravaganza – Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). It was heralded as one of the most anticipated movies of all time prior to its release and McClung was right in the middle of it.

“Studios were scrapping around for any big science fiction movie, chucking money at it everywhere,” McClung tells me over Zoom from his home in Pasadena, California. “They weren’t so bothered by the quality just as long as it got made.”

Pat Clung’s Journey from Model Shop to James Cameron’s Digital Domain

A year before George Lucas released his game-changing Star Wars (1977) to the world, a young McClung left the military. He was awe-inspired by the film and began plotting a way into the industry. It was Lucas’ sci-fi world that led McClung to the local craft store to start creating miniatures.

With a “terrible [in]ability” to draw and no alternatives, he began building spaceships and winning local competitions, before taking the winning photos to production companies. It was here where he found his feet.

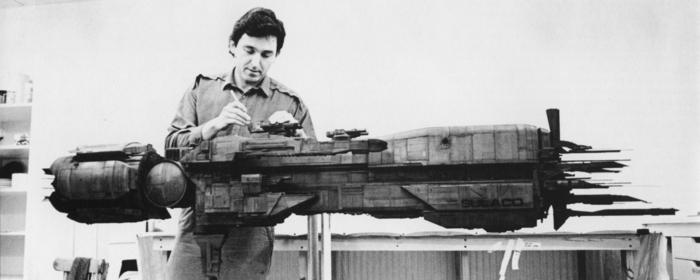

His fast ascendancy to the major pictures was common at the time. Studios needed to recruit people with skills that few had. As a result, he ended up working on Star Wars Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980). He followed the two colossal SF franchises with further model shop successes in classics such as Ghostbusters (1984), Aliens (1986), Die Hard (1988), and The Abyss (1989), before finishing his model shop supervising days on Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 (1995). It was quite the journey already.

But then came the visual effects boom. Those years working in the army with computers eventually came to the surface and McClung stood out. He had met The Terminator (1984) auteur James Cameron several years earlier when the two worked in the model shop for Roger Corman’s Star Wars-inspired romp, Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), and it was this connection in the B-movie trenches that helped him make the leap. In 1993, Cameron set up the FX company Digital Domain with the Oscar-winning makeup effects artist Stan Winston and former Industrial Light & Magic head honcho Scott Ross in order to develop new VFX tools for filmmakers.

“I realized that the industry was slowly shifting away from model work and into the digital age. This was what Digital Domain was edging towards. I asked Jim Cameron, a co-founder of the company if I could move up to supervising visual effects. This was my interest in computers becoming my nine-to-five job,” McClung says with a beaming smile.

“Cameron told me yes and it all started from there. I have a very strong background in miniatures and physical effects, what we call special effects. I know the whole process behind the scenes.”

After heading the visual effects on the Steve Martin comedy Sgt. Bilko (1996) and seldom-recalled conspiracy thriller Chain Reaction (1996) starring Keanu Reeves, McClung took on his first big production with Dante’s Peak in 1995. It was his work on Aliens, which had come about in part from working with Cameron on Battle Beyond the Stars, that helped pave the way for him to join production on Armageddon.

“Gale Anne Hurd, who was a producer on Aliens, ended up becoming a producer at the eleventh hour on Dante’s Peak. When that was done, she began working on Armageddon as the original producer. I came in and met Bay, and told him sort of my approach to things. He was right on board straight away with my vision,” explains McClung.

Working with Michael Bay

Bad Boys (1995) and The Rock (1996) having already established Michael Bay as a director with an eye for popcorn hits, Armageddon (1998) was an eye-opening experience for McClung who was touted by Bay as “the best in the business.” In only his second visual effects supervision role, he was tasked with heading an in-house VFX unit on Disney’s big summer release.

“Bay was a serial planner; only Cameron could trump him in that department. He is incredibly visual and knew what he wanted on screen – he could communicate it all.

“I think Armageddon was his best film,” says McClung, despite Bay revealing to the Miami Herald in 2013 he regards it as his worst film.

“One thing I learned when working closely with directors, and it is one of the surprises: I always made this assumption that the directors, as you’d expect, knew everything about the entire film, everything that was going to happen – they’d have planned out. That isn’t the case. A lot of directors were – surprisingly – not very visual, but Michael Bay had a very distinct idea of what he wanted the feel of things. He was good with design.

“He may have yelled at me a couple of times, which was semi-deserved when I’d deliver something below-par – but he was great to work with and a good guy. Usually full of energy; he never stops – no breaks whatsoever. I would have to show him motion tests and what have you on VHS tape and it was hard to get him to look at the stuff because he was so busy.”

By the time Armageddon came around, the digital revolution was well and truly underway. Technology was advancing at a rapid rate; what was seen as far-fetched a year before could now be considered doable. Nonetheless, McClung’s experience in miniatures was what clinched him the role at the time.

“It was obvious that the film required a lot of [miniature] work. Some of the software that was coming out was great, but it wasn’t quite ready yet. I knew how to do it physically – it was what I had become accustomed to.”

The Role of Dream Quest Images

In the 1990s, visual effects companies were experiencing a large rate of chopping and changing, with a large proportion of them constantly on the brink of collapsing, according to McClung. While the demand for work was there, the cost of production usually resulted in going over budget. It was not unusual for VFX companies to open their own pockets to keep progress going in the hope more work would come at the end.

On this particular set, McClung had to manage a set of independent teams in order to put together effects shots. This involved more than a dozen companies – perhaps too many cooks spoil the broth – for McClung and his partner Richard Hoover to supervise. It was a massive task and there was pressure from the studio side to justify their latest acquisition.

“At the time, Disney Studios had bought a company called Dream Quest Images and pumped a lot of money into its digital division,” he says. “The head of production told me I can use anybody, but really he wanted me to use Dream Quest. So Rich Hoover, the other supervisor, and I split up the show.

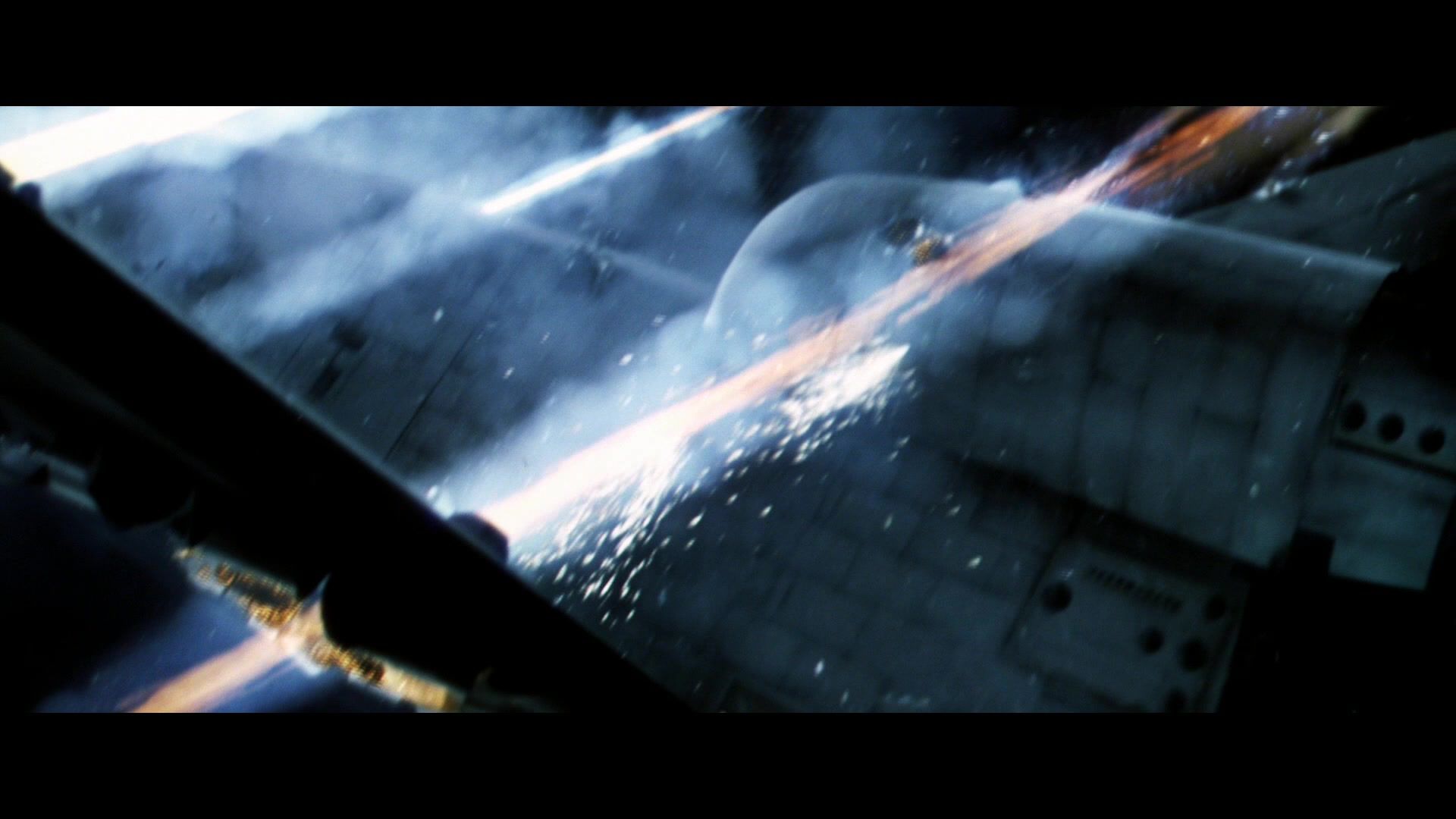

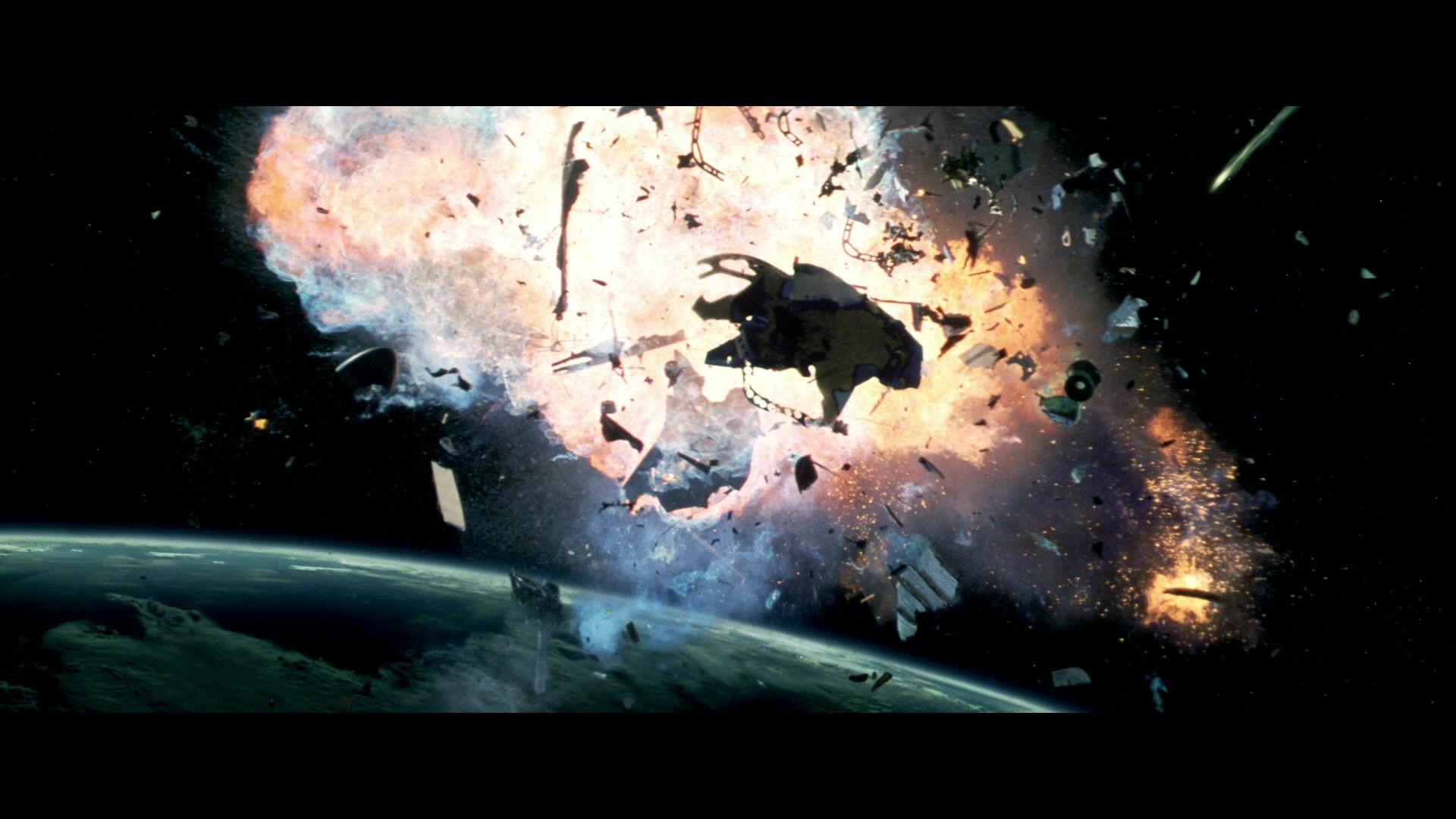

“Dream Quest did do all the exterior asteroid shots with all the clouds, colorful asteroids, dust, etc., etc., and had the digital firepower to pull that off.”

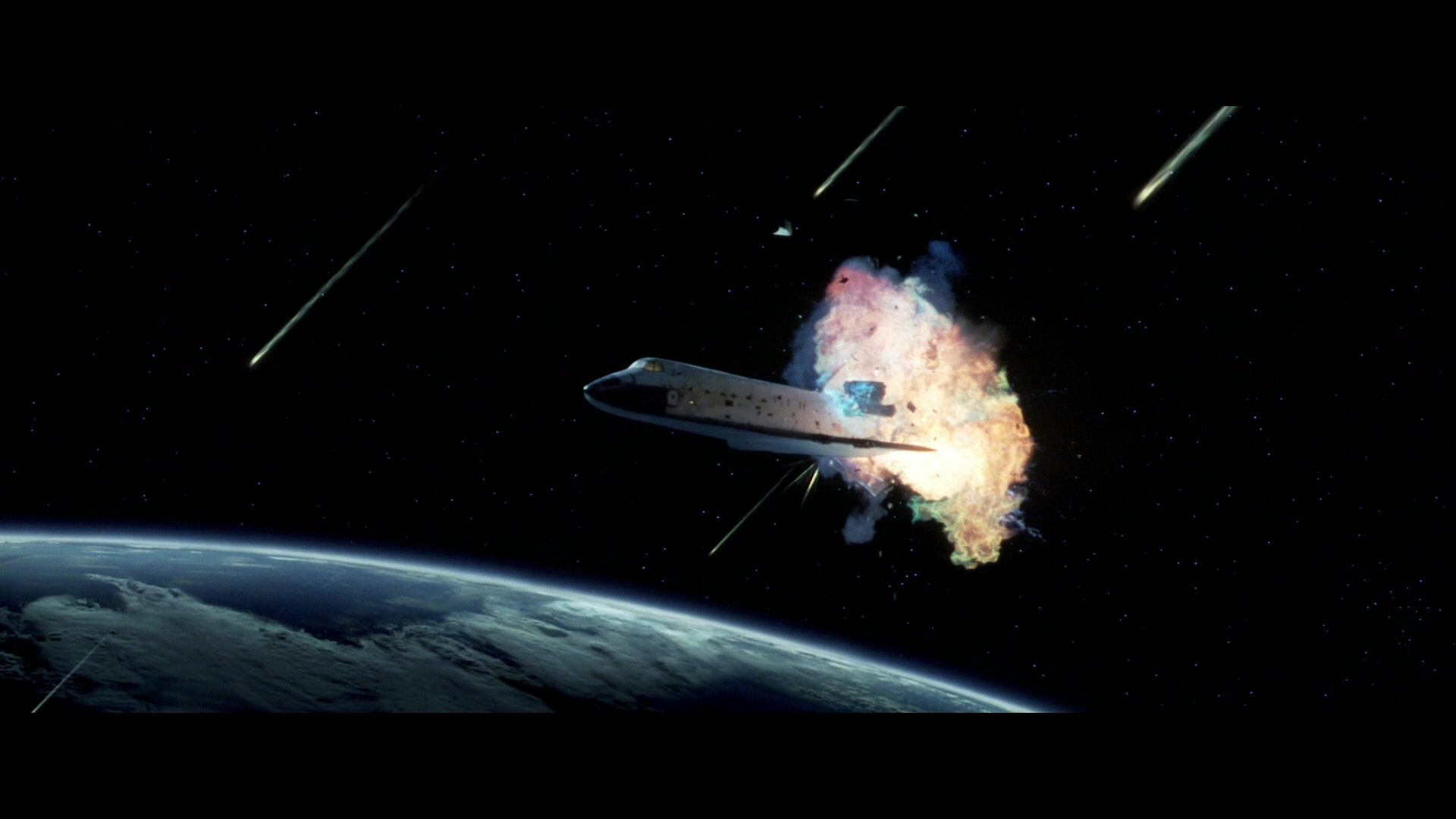

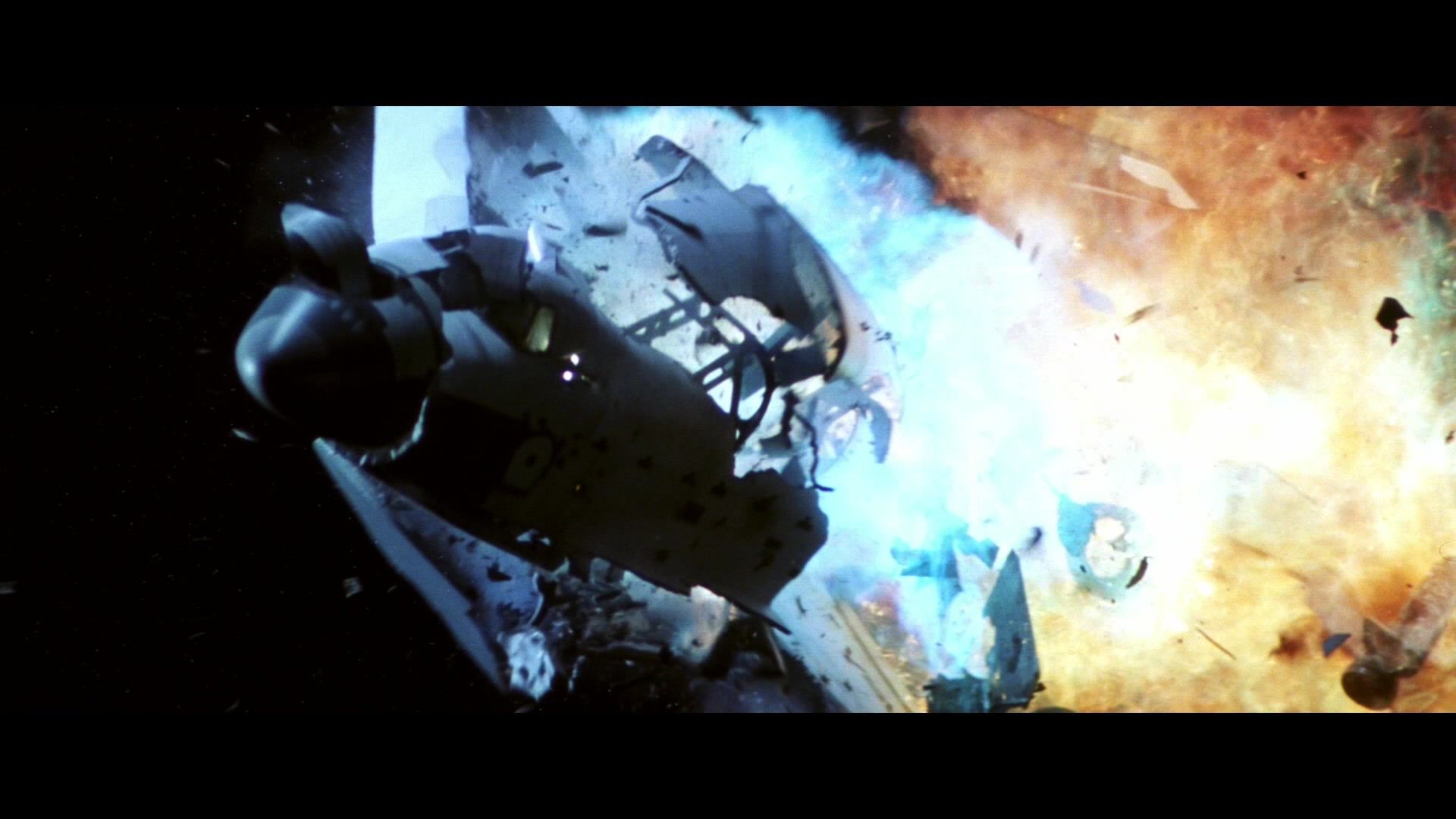

Under Hoover’s management, Dream Quest Images produced the bulk of the asteroid and space shuttle shots, but even then it was impossible to cleanly delineate responsibilities. “There was a lot of work going on at this time,” McClung explains. “I considered doing an entirely digital shuttle. But I thought, well, I’m going to have to farm out a number of these shots to different companies.”

An example of this approach would be the Paris explosion scene towards the end of the film, in which Digital Domain composited the explosion, with Matte World Digital providing the aftermath shot.

Armageddon, like many sci-fi disasters of the 1990s, had its fair share of on-set troubles at the time. It was scribed by nine writers, with star Ben Affleck’s famous jibes at Bay for its absurd plot going viral years later (“You mean it’s a real plan at NASA to train oil drillers?” – “Just shut your mouth.”). Nonetheless, collaboration between the visual effects companies showcased what can be achieved with a common goal in mind.

“We would tend to hand off an entire sequence to one company, as they’ll be able to do all those shots,” says McClung. “This would generally be based on the assets at their disposal. So I decided to shoot miniature motion for the shuttles. That way, I could just send a blue screenshot of a shuttle to a company to composite the background or what have you.”

Reflecting on the Finished Film

No film in 1998 could quite compare from a scale perspective to Armageddon. It was the effects movie of the summer, with a budget of US$140 million. Rather remarkably, months prior to release, Disney handed over US$3 million to create further visual effects to differentiate the movie from the similarly themed asteroid caper Deep Impact (1998).

In total, McClung supervised 350 VFX shots, and unlike most films that were creating digital effects from scratch, the film held on to some of the more traditional methods by continuing to use miniatures (such as New York’s Grand Central Station above, which was shot in miniature and then composited with CG fire and fury), albeit not always very miniature.

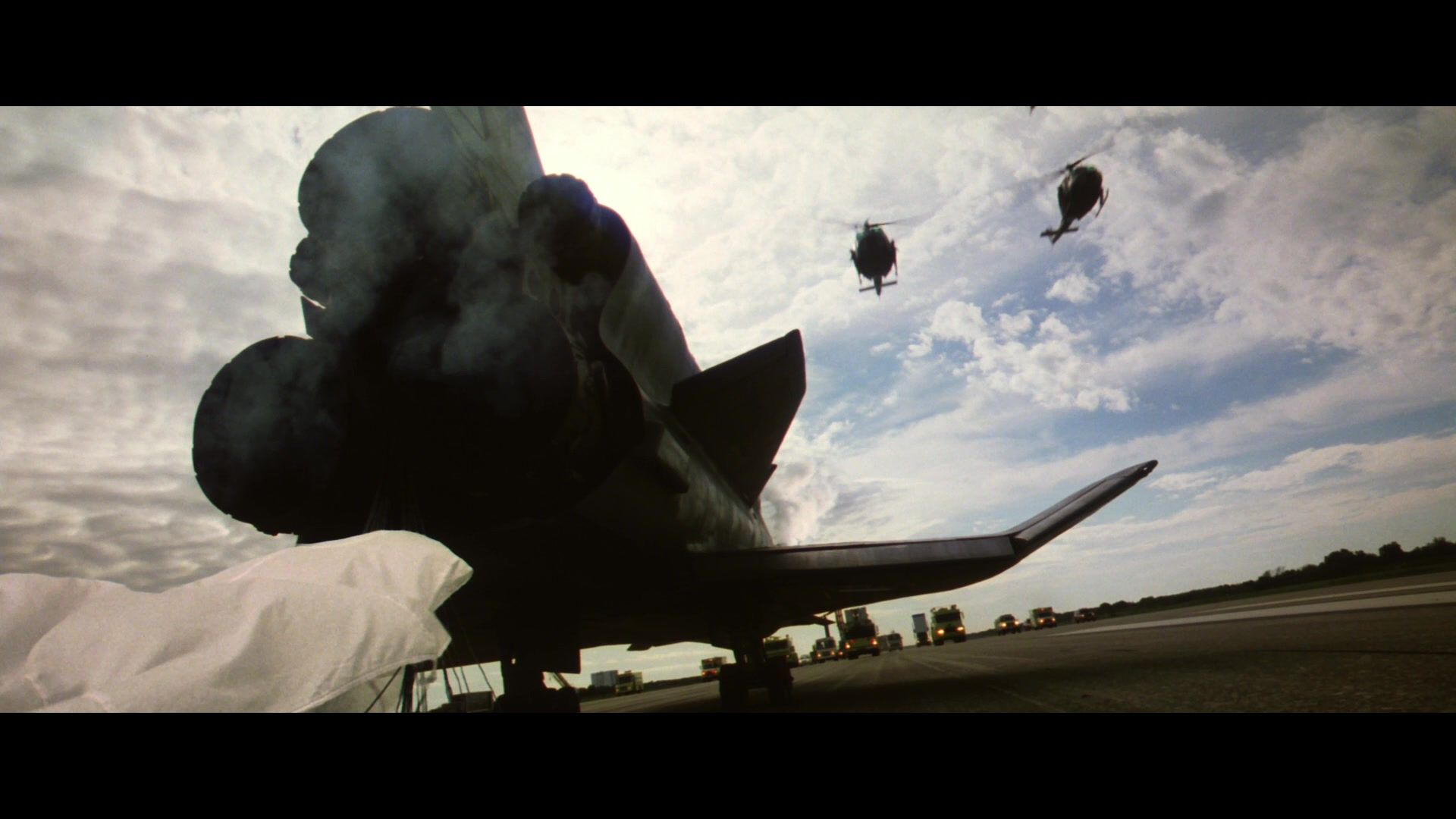

“We built a large quarter-scale shuttle, it was huge, for a number of shots like on the planet and when the door opens – which we shot in the parking lot.”

“We set up an office in Culver City, which originally was the backlot for Desilu Studios after it bought RKO. In the early ‘70s, it was replaced with big warehouses, and a lot of television was shot there. This is where we started building the miniatures and shooting them there. We built two huge sets: the Freedom and Independence miniatures for the shuttles.

“One of my favorite shots in Armageddon, it wasn’t particularly hard to capture, was shot by Mark Loso at Rainmaker. It was a 180-degree pan as Freedom arrived back home; we shot on the runway at John F. Kennedy Space Center at NASA.

“A guy from Dream Quest actually captured it, It was a really great shot and they put the little trails coming off the wings on the shuttle – it looks so real. It showcased a collaborative set where we all wanted to work together.

“Any visual effects supervisor will say every movie involves long hours, and Armageddon was no different, but our post-productions days were constantly longer than 16 hours. It was tough.”

The 1998 Oscar Snub

“The special visual effects, including seamless computer imagery and digitalization, are masterful. Oscar nominations surely will be in order for the terrific effects team headed by visual effects supervisor Pat McClung.”

So read The Hollywood Reporter’s review of Armageddon, written by Duane Byrge.

While McClung regards Armageddon as one of the most positive and gratifying experiences of his career, memories of heartbreak at the 1998 Academy Awards still resonate with him today. Having received his second nomination – McClung was previously nominated for True Lies a few years before – he was certain this time he was going to bring home a shiny addition to the mantlepiece.

“You know, I had been nominated with John Bruno, a dear friend of mine, on True Lies. It was Bruno who asked me to come over to Digital Domain and got me involved. We wanted to win, but it was a lot of fun to go to the ceremony and the dinner, everything that follows,” admits McClung.

“But I gotta say, I really thought it was just a formality for us to collect the award for Armageddon. All of us did – we just assumed we would be picking it up. But now I’ve been in the Academy for a long time, I now know the reasons behind us not winning. When Disney was on the publicity trail sending out tapes, but for some reason, the company didn’t want to push Armageddon.”

“When I first arrived on set, the head of production Bruce Hayes said he really wanted to win the Oscar for visual effects on this film. Even [producer] Jerry Bruckheimer called me when we had finished saying he thought we would get it. But Disney decided to push Mighty Joe Young, which is not a great movie, in my opinion.

“In the end What Dreams May Come took the award. I was gutted. It was a huge shock. I remember after we lost, at the dinner catered by [celebrity chef] Wolfgang Puck and heading to the Armageddon table with nobody there. They’d all left, all pissed off. At the end of the day, the Academy is just a club. That’s all it is. It’s not federally funded so people can vote however they want.

“I really thought we deserved it – all the people on the film did such a good job and we were super happy with everything. So that was a huge disappointment, but, you know, what are you going to do?” concludes McClung, with a tinge of what could’ve been.

A member of the VFX old guard, McClung’s a Swiss army knife behind the scenes; he has made contributions in a plethora of areas on production. While Armageddon has its critics, few can argue with his resume with credits that any budding visual designer would be proud to replicate. While his attention has moved into TV – working on the likes of Marvel’s Runaways, Scorpion, and The Walking Dead – the veteran certainly made a mark on 1990s sci-fi.

This article was first published on November 27th, 2020, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂